Summary:

The historic Egyptian city of Alexandria is facing an alarming surge in building collapses, with structures once considered resilient now crumbling at a rate of 40 per year. A new study published in Earth’s Future attributes this crisis to rising sea levels and seawater intrusion, warning that other coastal cities—including those in California—face similar threats.

Researchers from USC and international institutions tracked shoreline retreat, groundwater changes, and the chemical makeup of soil samples to reveal how seawater is eroding foundations from the bottom up. Their findings challenge the assumption that coastal cities are only at risk when seas rise significantly, showing instead that even small increases can destabilize infrastructure.

The study also offers solutions: nature-based defenses like sand dunes and vegetation barriers could help mitigate the damage. As climate change accelerates coastal erosion worldwide, the researchers emphasize that protecting historic cities isn’t just about preserving architecture — it’s about safeguarding cultural heritage and urban resilience.

Coastal erosion threatens this ancient city — and others much closer to home

The new USC study reveals a dramatic surge in building collapses in the ancient Egyptian port city of Alexandria, directly linked to rising sea levels and seawater intrusion.

Once a rare occurrence, building collapses in Alexandria — one of the world’s oldest cities, often called the ‘bride of the Mediterranean’ for its beauty — have accelerated from approximately one per year to an alarming 40 per year over the past decade, the researchers found.

“The true cost of this loss extends far beyond bricks and mortar. We are witnessing the gradual disappearance of historic coastal cities, with Alexandria sounding the alarm. What once seemed like distant climate risks are now a present reality,” said Essam Heggy, a water scientist at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering and the study’s corresponding author.

“For centuries, Alexandria’s structures stood as marvels of resilient engineering, enduring earthquakes, storm surges, tsunamis and more. But now, rising seas and intensifying storms — fueled by climate change — are undoing in decades what took millennia of human ingenuity to create,” said Sara Fouad, a landscape architect at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and the study’s first author.

Coastal erosion: Sinking cities and rising seas

Even small sea level increases — just a few centimeters — can have devastating effects, Heggy said, threatening even cities as historically resilient as Alexandria, which has withstood centuries of earthquakes, invasions and fires, and even a modern metropolis like Los Angeles, where flash floods and mudslides are now complicating recovery from the recent wildfires.

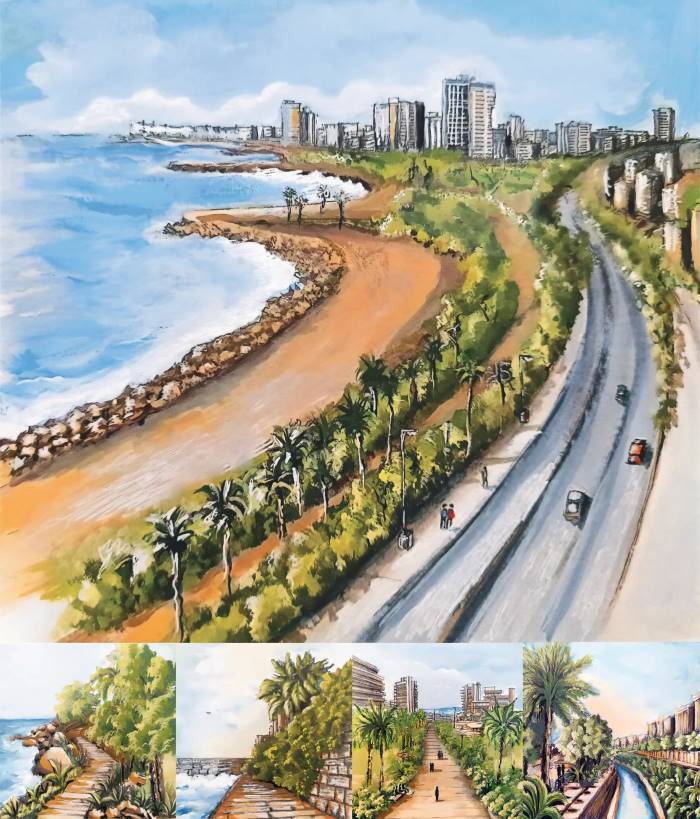

Developing waterways helps the city handle climate extremes and connects people to well-maintained urban spaces, linking the inner city to the coast. The strategy for future coastal resilience in Alexandria includes maintaining, enhancing or restoring a green belt along the coastline. Credit: Illustrations courtesy of Essam Heggy and Sara Elsayed

Published in Earth’s Future, an AGU journal, the study coincides with troubling findings from NASA and NOAA showing that parts of California — including the San Francisco Bay Area, Central Valley and coastal Southern California — are sinking. These minor elevation changes can significantly heighten flood risks and saltwater intrusion, scientists warn.

Like Alexandria, California’s coastal cities face growing threats from saltwater intrusion, which weakens infrastructure, degrades water supplies and drives up the cost of living.

“Our study challenges the common misconception that we’ll only need to worry when sea levels rise by a meter,” Heggy said. “However, what we’re showing here is that coastlines globally, especially Mediterranean coastlines similar to California’s, are already changing and causing building collapses at an unprecedented rate.”

Tracking coastal erosion in Alexandria, Egypt

The researchers used a three-pronged approach to assess the impact of shoreline changes on Alexandria’s buildings.

First, they created a detailed digital map using geographic information system technology to identify the locations of collapsed buildings across six districts of the city’s historic urban area, one of its most densely populated regions. The map catalogs key details about each structure, including its location, size, construction materials, age, foundation depth and number of floors.

The data, collected from site visits, government reports, news archives and statements from private construction companies, spans 2001 to 2021 and includes both fully and partially collapsed buildings.

Next, they combined satellite imagery with historical maps from 1887, 1959 and 2001 to track shoreline movement and gain a deeper understanding of how parts of Alexandria’s 50-mile coastline have moved tens of meters inland over the past two decades. By calculating the rate of shoreline retreat over the past century, the researchers studied how the shrinking coastline is raising groundwater levels, bringing them into contact with the foundations of coastal buildings.

Finally, the team analyzed chemical “fingerprints” known as isotopes in soil samples to examine the effects of seawater intrusion. They measured specific isotopes, like B7, in each sample to assess the soil’s mechanical properties. Higher B7 levels indicate stronger, more stable soil, while lower levels suggest erosion.

“Our isotope analysis revealed that buildings are collapsing from the bottom up, as seawater intrusion erodes foundations and weakens the soil. It isn’t the buildings themselves, but the ground underneath them that’s being affected,” said Ibrahim H. Saleh, a soil radiation scientist at Alexandria University and one of the study’s co-authors.

“Our study demonstrates that coastal buildings are at risk of collapsing even without directly encroaching on the seawater as widely believed,” Heggy added.

A nature-based solution to protect coastal cities

To combat coastal erosion and seawater intrusion, the researchers propose a nature-based solution: creating sand dunes and vegetation barriers along the coastline to block encroaching seawater and hence preventing seawater intrusion from pushing up groundwater levels to building foundations. This sustainable, cost-effective approach can be applied in many coastal densely urbanized regions globally, said Steffen Nijhuis, a landscape-based urbanist from Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands and study co-author.

“Preserving the diverse architectural attributes of Mediterranean historic cities is a powerful reminder of how landscape transformation has played a crucial role in creating climate-resilient societies,” said Udo Weilacher, landscape architect at TUM and study co-author.

“Historic cities like Alexandria, which represent the cradle of cultural exchange, innovation and history, are crucial for safeguarding our shared human heritage,” Heggy said. “As climate change accelerates sea level rise and coastal erosion, protecting them isn’t just about saving buildings; it’s about preserving who we are.”

Journal Reference:

Fouad, S. S., Heggy, E., Amrouni, O., Hzami, A., Nijhuis, S., Mohamed, N., et al., ‘Soaring building collapses in southern mediterranean coasts: Hydroclimatic drivers & adaptive landscape mitigations’, Earth’s Future 13, e2024EF004883 (2025). DOI: 10.1029/2024EF004883

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Nina Raffio | University of Southern California

Featured image credit: Incredibly Madd | Pexels