Summary:

Greenland’s glaciers are fracturing more rapidly as the ice sheet responds to climate change, with crevasses expanding in size and depth at a faster pace than previously detected.

A new study, published in Nature Geoscience, used high-resolution 3D surface maps to analyze changes in Greenland’s ice from 2016 to 2021. Researchers led by Durham University found that where glaciers flow more quickly, crevasses have grown significantly — up to 25% in some areas. This acceleration, linked to rising ocean and air temperatures, may further speed up ice loss from Greenland, which has already contributed approximately 14mm to global sea level rise since 1992.

Scientists warn that the continued expansion of these fractures could trigger a domino effect, intensifying glacier movement and ice loss. The study provides crucial new data to improve predictions of how the Greenland Ice Sheet will evolve in a warming world.

The Greenland Ice Sheet is cracking open more rapidly as it responds to climate change

The warning comes in a new large-scale study of crevasses on the world’s second largest body of ice.

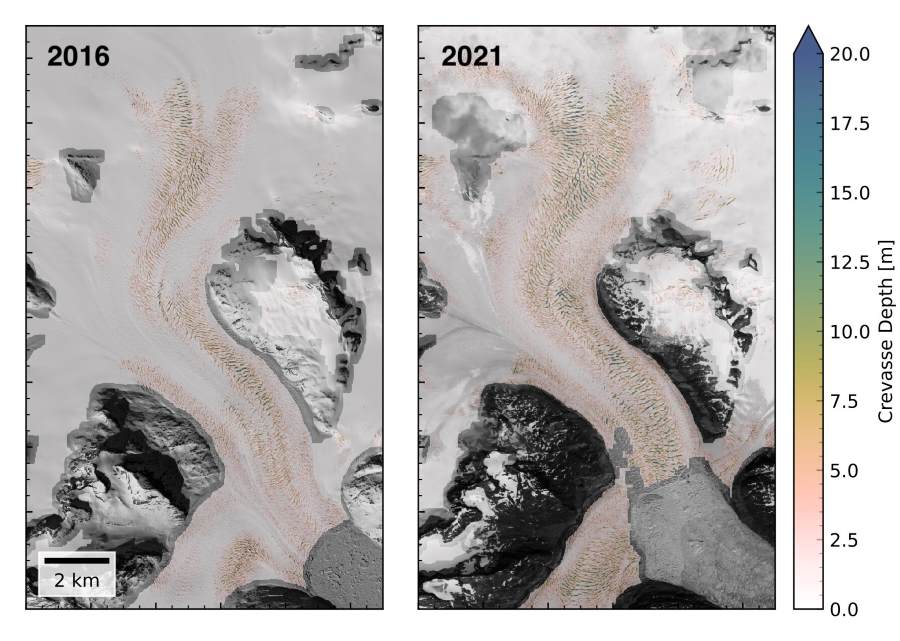

Using 3-D surface maps, scientists led by Durham University, UK, found crevasses had significantly increased in size and depth at the fast-flowing edges of the ice sheet over the five years between 2016 and 2021.

This means the increases in crevasses are happening more quickly than previously detected. Crevasses are wedge-shaped fractures or cracks that open in glaciers where ice begins to flow faster. The researchers say that crevasses are also getting bigger and deeper where ice is flowing more quickly due to climate change, and that this could further speed up the mechanisms behind the loss of ice from Greenland.

They hope their findings will allow scientists to build the effects of ice damage and crevassing into predictions of the future behaviour of the Greenland Ice Sheet.

Sea level rise

Greenland has been behind approximately 14mm of sea level rise since 1992. This is due to increased melting from the ice surface in response to warmer air temperatures, and increased flow of ice into the ocean in response to warmer ocean temperatures, which are both being driven by climate change.

Greenland contains enough ice to add seven metres (23 feet) of sea level rise to the world’s oceans if the entire ice sheet were to melt. Research has shown that Greenland could contribute up to 30cm (one foot) to sea level rise by 2100.

Bigger and deeper crevasses

For this latest study, the Durham-led researchers used more than 8,000 3-D surface maps, created from high-resolution satellite imagery, to identify cracks in the surface of the ice sheet and show how crevasses had evolved across Greenland between 2016 and 2021.

The research found that, at the edges of the ice sheet where large glaciers meet the sea, accelerations in glacier flow speed were associated with significant increases in the volume of crevasses. This was up to 25 per cent in some sectors (with an error margin of plus/minus ten per cent).

These increases were offset by a reduction in crevasses at Sermeq Kujalleq, the fastest-flowing glacier in Greenland, which underwent a temporary slowdown in movement during the study period.

This balanced the total change in crevasses across the entire ice sheet during the study period to plus 4.3 per cent (with an error margin of plus/minus 5.9 per cent). However, Sermeq Kujalleq’s flow speed has since begun increasing again – suggesting that the period of balance between crevasse growth and closure on the ice sheet is now over.

Study lead author Dr Tom Chudley, a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in the Department of Geography, Durham University, UK, said: “In a warming world, we would expect to see more crevasses forming. This is because glaciers are accelerating in response to warmer ocean temperatures, and because meltwater filling crevasses can force fractures deeper into the ice. However, until now we haven’t had the data to show where and how fast this is happening across the entirety of the Greenland Ice Sheet.

“For the first time, we are able to see significant increases in the size and depth of crevasses at fast-flowing glaciers at the edges of the Greenland Ice Sheet, on timescales of five years and less.

“With this dataset we can see that it’s not just that crevasse fields are extending into the ice sheet, as previously observed – instead, change is dominated by existing crevasse fields getting larger and deeper.”

Increased crevassing has the potential to speed up the loss of ice from Greenland.

Study co-author Professor Ian Howat, Director of the Byrd Polar & Climate Research Center at The Ohio State University, USA, said: “As crevasses grow, they feed the mechanisms that make the ice sheet’s glaciers move faster, driving water and heat to the interior of the ice sheet and accelerating the calving of icebergs into the ocean.

“These processes can in turn speed up ice flow and lead to the formation of more and deeper crevasses – a domino effect that could drive the loss of ice from Greenland at a faster pace.”

The research used imagery from the ArcticDEM project, a National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and National Science Foundation (NSF) public-private initiative to automatically produce a high-resolution, high-quality digital surface model of the Arctic. ArcticDEM imagery was provided by the Polar Geospatial Center.

Professor Howat added: “The ArcticDEM project will continue to provide high-resolution Digital Elevation Models until at least 2032. This will allow us to monitor glaciers in Greenland and across the wider Arctic as they continue to respond to climate change in regions experiencing faster rates of warming than anywhere else on Earth.”

The research team also included Dr Michalea King from the University of Washington and Dr Emma MacKie at the University of Florida, both USA.

***

The study was funded by a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship, NASA, and the National Science Foundation Office for Polar Programs.

Journal Reference:

Chudley, T.R., Howat, I.M., King, M.D., MacKie, E.J., ‘Increased crevassing across accelerating Greenland Ice Sheet margins’, Nature Geoscience (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-024-01636-6

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Durham University

Featured image: Crevasses at Store Glacier, a marine-terminating outlet glacier of the western Greenland Ice Sheet. Credit: Tom Chudley | Durham University