Prehistoric kangaroos in southern Australia were far more adaptable eaters than previously believed, according to a study published in Science.

The research, led by Flinders University and the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT), suggests that dietary flexibility may have helped these marsupials survive past climate changes, though it challenges earlier theories about their eventual extinction.

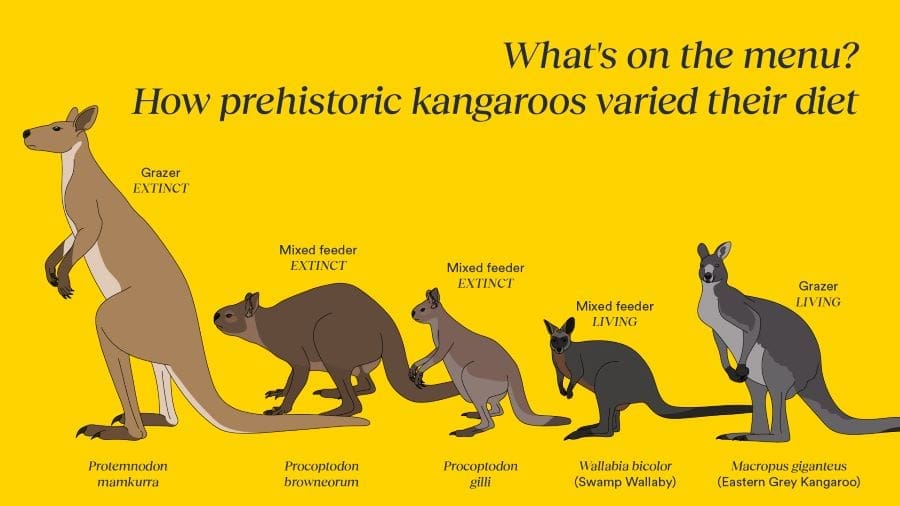

By analyzing microscopic wear patterns on fossilized kangaroo teeth, the researchers found that many prehistoric kangaroo species were generalists capable of consuming diverse diets. This insight refutes the long-held idea that megafaunal extinctions, including those of large kangaroo species, were primarily due to dietary specialization. Instead, the study highlights a complex interplay of factors that likely influenced the survival of these species.

The research team focused on kangaroo fossils from the Victoria Fossil Cave in South Australia’s Naracoorte Caves World Heritage Area. This site holds the most extensive collection of fossilized kangaroos from the Pleistocene epoch, spanning 2.6 million to 12,000 years ago.

“Our study shows that most prehistoric kangaroos at Naracoorte had broad diets. This dietary flexibility likely played a key role in their resilience during past changes in climate,” said lead researcher Dr. Sam Arman, from MAGNT and Flinders University.

Using Dental Microwear Texture Analysis, the study compared the diets of 12 extinct kangaroo species with those of 17 modern species. The findings contradict earlier assumptions that kangaroo species like sthenurines, with their distinctive short-faced anatomy, perished due to their inability to adapt their diets to changing vegetation patterns.

“Most of the Naracoorte kangaroo species actually had similar everyday diets, which would reflect foods that were most nutritious and readily accessible,” Dr. Arman explained. “Having the hardware though, to eat more challenging foods would have helped them get through seasons or years when their preferred food was rare. An analogy might be my 4×4. Most of the time, I don’t need to engage four-wheel drive, but this capability becomes crucial when I do need it.”

Professor Gavin Prideaux of Flinders University, a co-author of the study, emphasized how understanding the ecological roles of extinct megafauna provides context for modern ecosystems: “By shedding light on the ecological roles of Australia’s marsupial megafauna, we will develop a better understanding of how its modern ecosystems evolved. Among other things, this might help to contextualise why Australia has been so vulnerable to introduced large mammals, such as pigs, camels, deer and horses.”

The study used scans from 2,650 kangaroo teeth to model dietary patterns and regional variations. This extensive analysis allowed researchers to discern significant differences between species and individual feeding habits, offering new insights into the diets of Pleistocene kangaroos.

“This allowed us to capture the degree to which diets vary between individuals and regions for modern species, and then use this as a basis for investigating diets of fossil species through time,” said Flinders Palaeontology Lab manager and co-author Grant Gully.

While dietary adaptability was clearly an advantage, the researchers suggest other factors, such as body size, locomotion, and interactions with the environment and early humans, likely played critical roles in the extinction of megafaunal species during the Pleistocene.

Future research aims to extend the dataset to other fossil sites across Australia, particularly those from 60,000 to 40,000 years ago, to better understand the full picture of megafaunal extinctions.

Journal Reference:

Samuel D. Arman et al. ‘Dietary breadth in kangaroos facilitated resilience to Quaternary climatic variations’, Science 387, 167-171 (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adq4340

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Flinders University

Featured image: Reconstruction of the Naracoorte Caves during the Pleistocene. Credit: Peter Schouten