Table of Contents

Study assesses the benefits of alfalfa-almond intercropping

Wiley – The practice of growing different but complementary plants within a given area, also known as intercropping, offers numerous climate and environmental benefits such as reduced soil erosion, weed suppression, nitrogen fixation (the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen to nitrogen compounds that can be used by plants and other organisms), and pollinator benefits.

New research published in Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment reveals the increased land use efficiency and environmental benefits in an alfalfa–almond intercropped ecosystem under a Mediterranean climate.

Investigators found that intercropping alfalfa plants with almond trees during the winter (when almond trees are dormant) reduced field water loss via evaporation and significantly reduced winter soil nitrate leaching compared with control plots.

The findings indicate that intercropping alfalfa can be a viable approach to capture and convert winter rain and nitrogen losses into revenues for almond farmers.

“The ecosystem benefits observed in this unique alfalfa-almond intercropped agroecosystem were mainly attributed to augmentation in farm resource use efficiency and revenues generated during the normally non-productive winter season,” said corresponding author Touyee Thao, PhD, of USDA-ARS, San Joaquin Valley Agricultural Sciences Center. “Other aspects such as tree growth and productivity, soil microbial activity, and plant root interaction are also being investigated by colleague researchers.”

Journal Reference:

Touyee Thao, Sultan Begna, Lauren Hale, Khaled M. Bali, Dong Wang, Suduan Gao, ‘Intercropping alfalfa during almond orchard establishment reduces winter soil nitrogen and water losses, provides on-farm revenue’, Agrosystems Geosciences & Environment 8 (1) e70024 (2025). DOI: 10.1002/agg2.70024

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Wiley

Mediterranean sharks continue to decline despite conservation progress

Alan Williams | University of Plymouth – Overfishing, illegal fishing and increasing marketing of shark meat pose significant threats to the more than 80 species of sharks and rays that inhabit the Mediterranean Sea, according to a new study.

The research examined current levels of legislation in place to protect elasmobranch populations (which include sharks, rays and skates) within each of the 22 coastal states of the Mediterranean region.

Across those countries – stretching from Spain and Morocco in the west to Israel, Lebanon and Syria in the east – the researchers identified more than 200 measures that concern elasmobranchs in some way, ranging from national legislation to implemented conservation efforts by various non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

European Union countries generally led the implementation of more measures than non-EU ones, with Spain having the highest number of measures in place. Governments were responsible for leading 63% of measures, mainly relating to legal requirements.

However, while elasmobranchs have made it onto many policy agendas, the study found considerable differences in how effectively any legislation was being monitored with no single source for tracking progress in the conservation and management of sharks at national levels.

Experts and NGOs across the region also highlighted that sharks are increasingly being landed intentionally and unintentionally by fishers, often to meet the demand for shark products.

However, there is often little control in place where sharks are landed, leading researchers to call for increased monitoring to protect threatened species, in addition to more public education and incentives for fishers to use equipment that is less threatening to shark species.

The research, published in the journal Biological Conservation, represents the first region-wide assessment of actions being taken to protect shark populations through international law.

It was led by Dr Lydia Koehler and Jason Lowther, both experts in environmental law from the School of Society and Culture at the University of Plymouth.

Dr Koehler, Associate Lecturer and a member of the IUCN World Commission on Environmental Law (WCEL), said: “Sharks have been part of the marine ecosystem for millions of years with an evolutionary history that predates the dinosaurs. There are over 1,000 species of elasmobranchs worldwide, and they fulfil a variety of ecological roles, whether as apex predators that maintain healthy populations of prey species or a food source for other predators. However, many shark species in the Mediterranean have seen drastic declines in past few decades with over half of the species being threatened by extinction, largely due to overfishing and related pressures such as bycatch. Finding effective ways to conserve them is, therefore, of critical importance.”

Mr Lowther, Associate Professor of Law, added: “This study has shown substantial differences in countries’ efforts around shark conservation. That may be linked to access to resources, available expertise and capacities, and a general willingness to develop and implement measures in light of other competing pressures. Achieving positive outcomes for these species requires not only government support but also sustained political will across election periods and a steadfast long-term commitment to driving change. It also requires the integration of communities in the Mediterranean region, and our view is that this work presents a starting point in that process.”

Recommendations to protect the Mediterranean’s sharks

In the study, the authors have listed a number of recommendations which they feel could be used to better conserve and protect shark and ray species right across the Mediterranean Sea. They are:

- Increase transparency throughout the system: Improve reporting templates to facilitate more detailed answers on actions taken, and account for specific contributions by other key actors, would facilitate increased transparency;

- Expand cooperation and integration of the fishing community and use of social science: Shark governance issues are unlikely to be solved without the support of the fishing community, and community dependencies and structures must be considered for successful shark governance;

- Extend spatial conservation measures: Amending the objectives and management for existing Marine Protected Areas that host sharks could be one way to approach better conservation for these species;

- Increase compliance to reduce bycatch: Effectively applying existing legislation could significantly increase knowledge on incidental shark bycatch in the region;

- Increase access to funding, especially for collaborative, cross-country actions: A review of existing and potential funding opportunities and priorities could help support the identification of conservation and management actions for threatened and endangered shark and ray species;

- Tailor research to policy needs to establish better regulatory measures: Coordinated research efforts across the region are needed to enable stock assessments and a wider understanding of trends in pressures, populations, etc.

Journal Reference:

Lydia Koehler, Jason Lowther, ‘Tracking implementation of shark-related measures and actions in the Mediterranean region in the context of international law’, Biological Conservation 302, 110930, (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.biocon.2024.110930

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Plymouth

Climate change linked with worse HIV prevention and care

University of Toronto – New challenges in HIV prevention and care are emerging due to climate change, according to a review published earlier this month in Current Opinions in Infectious Disease.

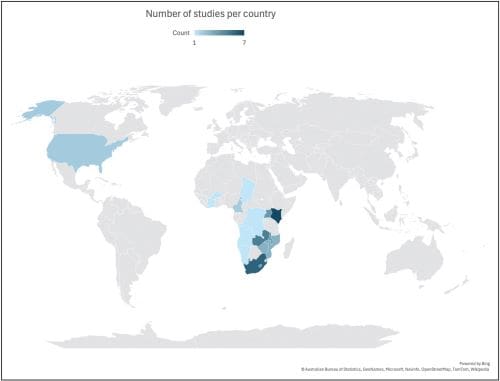

Researchers from the University of Toronto analyzed 22 recent studies exploring HIV-related outcomes in the context of climate change and identified several links between extreme weather events and HIV prevention and care.

Climate change-related extreme weather events, such as drought and flooding, were associated with poorer HIV prevention outcomes, including reduced HIV testing. Extreme weather events were also linked to increased practices that elevate HIV risk, such as transactional sex and condomless sex, as well as increases in new HIV infection.

“Climate change impacts HIV prevention through several mechanistic pathways,” says lead author Carmen Logie, Professor at the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work (FIFSW) at the University of Toronto and the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment, and Health. “Extreme weather events cause structural damage to health care infrastructure and increase migration and displacement, both of which disrupt access to HIV clinics for prevention and testing. We also see increases in practices that increase HIV risk due to climate change-related resource scarcity.”

The study also uncovered important implications for HIV care among those already living with HIV, such as reduced viral suppression, poorer treatment adherence, and worse physical and mental wellbeing.

“Extreme weather events present new challenges with access to HIV care and treatment adherence,” said co-author Andie MacNeil, PhD student at the FIFSW at the University of Toronto. “Multilevel strategies are needed to mitigate the effects of climate change on HIV care, such as long-lasting antiretroviral therapy, increased medication dispensing supplies, and community-based medication delivery and outreach programs.”

The authors highlighted several important gaps in the existing literature, including the lack of research on specific extreme weather events (e.g., extreme heat, wildfires, hurricanes) and in geographic areas with high climate change vulnerability and increasing HIV rates (e.g., the Middle East and Northern Africa).

They also described a persisting lack of knowledge on extreme weather events and HIV among key marginalized populations, including sex workers, people who use drugs, and gender diverse persons, as well as how extreme weather events interact with intersecting forms of stigma.

The researchers are hopeful that these findings can help offer ways forward for research, policy, and practice.

“Innovative HIV interventions, such as long-acting PrEP, mobile pharmacies and health clinics, and interventions that reduce food and water insecurity may all contribute to improving HIV care during extreme weather events. More research and evaluation is needed to test climate-change informed HIV prevention and intervention strategies,” said Logie. “The integration of disaster preparedness and HIV care provides new opportunities to optimize HIV care in our changing climate.”

Journal Reference:

Logie, Carmen H., MacNeil, Andie, ‘Climate change and extreme weather events and linkages with HIV outcomes: recent advances and ways forward’, Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 38(1):p 26-36 (2025). DOI: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000001081

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work | University of Toronto

Plant cells gain immune capabilities when it’s time to fight disease

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies – Human bodies defend themselves using a diverse population of immune cells that circulate from one organ to another, responding to everything from cuts to colds to cancer.

But plants don’t have this luxury. Because plant cells are immobile, each individual cell is forced to manage its own immunity in addition to its many other responsibilities, like turning sunlight into energy or using that energy to grow. How these multitasking cells accomplish it all — detecting threats, communicating those threats, and responding effectively — has remained unclear.

New research from Salk Institute scientists reveals how plant cells switch roles to protect themselves against pathogens.

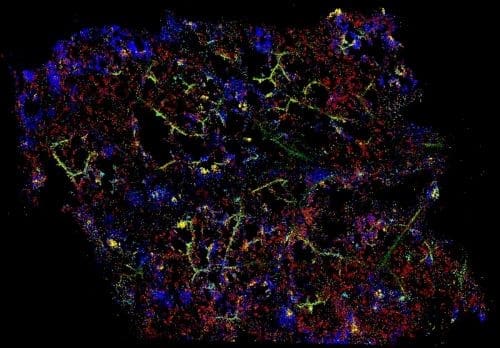

When a threat is encountered, the cells enter a specialized immune state and temporarily become PRimary IMmunE Responder (PRIMER) cells — a new cell population that acts as a hub to initiate the immune response. The researchers also discovered that PRIMER cells are surrounded by another population of cells they call bystander cells, which seem to be important for transmitting the immune response throughout the plant.

The findings, published in Nature, bring researchers closer to understanding the plant immune system—an increasingly important task amid the growing threats of antimicrobial resistance and climate change, which both escalate the spread of infectious disease.

“In nature, plants are constantly being attacked and require a well-functioning immune system,” says Professor Joseph Ecker, senior author of the study, Salk International Council Chair in Genetics, and Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. “But plants don’t have mobile, specialized immune cells like we do — they must come up with an entirely different system where every cell can respond to immune attacks without sacrificing their other duties. Until now, we weren’t quite sure how plants were accomplishing this.”

Plants encounter a wide range of pathogens, like bacteria that sneak in through leaf surface pores or fungi that directly invade plant “skin” cells. Since plant cells are stationary, when they encounter any of these pathogens, they become singularly responsible for responding and alerting nearby cells. Another interesting side effect of immobile cells is the fact that different pathogens may enter a plant at different locations and times, leading to varying immune response stages occurring simultaneously across the plant.

With factors like timing, location, response state, and more all at play, an infected plant is a complicated organism to understand. To tackle this, the Salk team turned to two sophisticated cell profiling techniques called time-resolved single-cell multiomics and spatial transcriptomics. By pairing the two, the team was able to capture the plant immune response in each cell with unprecedented spatiotemporal resolution.

“Discovering these rare PRIMER cells and their surrounding bystander cells is a huge insight into how plant cells communicate to survive the many external threats they face day-to-day,” says first author Tatsuya Nobori, a former postdoctoral researcher in Ecker’s lab and current group leader at The Sainsbury Laboratory in the United Kingdom.

The team introduced bacterial pathogens to the leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana — a flowering weed in the mustard family commonly used as a model in research. They then analyzed the plant’s response to comprehensively identify each cell’s state upon infection.

In doing so, they discovered a novel immune response state, which they called PRIMER, that emerged in cells at specific immune hotspots. The PRIMER cells expressed a new transcription factor — a type of protein that regulates gene expression — called GT-3a, which is likely an important upstream alarm for alerting other cells to an active plant immune response.

Additionally, the cells surrounding these PRIMER cells proved equally important. Dubbed “bystander cells,” the cells immediately neighboring PRIMER cells were expressing genes that enable long-distance cell-to-cell communication. The researchers plan to elucidate this relationship in future research, but for the time being, they suspect the interactions between PRIMER and bystander cells are key to propagating the immune response across the leaf.

This new spatiotemporal, cell-specific insight into the plant immune response is already available as a reference database for researchers worldwide. As pathogens continue to evolve and spread amid climate-related environmental changes and rising antibiotic resistance, the database offers an important springboard for preserving a future filled with healthy plants and crops.

“There is a lot of interest and demand for detailed cell atlases these days, so we’re excited to create a new one that is publicly available for other researchers to use,” says Ecker. “Our atlas could lead to many new discoveries about how individual plant cells respond to environmental stressors, which will be crucial for creating more climate-resilient crops.”

Other authors include Joseph Nery of Salk; Alexander Monell of Salk and UC San Diego; Travis Lee of Salk and Howard Hughes Medical Institute; Yuka Sakata, Shoma Shirahama, and Akira Mine of University of Kyoto in Japan; Jingtian Zhou of Arc Institute, USA.

The work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Human Frontiers Science Program.

Journal Reference:

Nobori, T., Monell, A., Lee, T.A. et al. ‘A rare PRIMER cell state in plant immunity’, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08383-z

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by The Salk Institute for Biological Studies

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay