Climate models are indispensable tools for predicting future climate scenarios, but their accuracy depends on the quality and relevance of the data input. While information from regions like Europe is abundant, data from parts of Africa, including Nigeria, has historically been scarce.

A new study, published in Buildings & Cities, has filled this gap, providing vital climate-related data from Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country.

The research, led by Chibuikem Chrysogonus Nwagwu, a master’s graduate in industrial ecology from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), focused on emissions linked to housing in Nigeria. Under the supervision of Professor Edgar Hertwich and doctoral researcher Sahin Akin, Nwagwu’s work produced detailed insights into housing structures, energy consumption, and potential emissions reductions.

Nigeria’s housing sector, shaped by rapid population growth, is a significant contributor to the country’s carbon emissions. The country’s population has doubled over the past three decades, surging from 100 million in the 1990s to over 220 million in 2024. Housing demand has grown in tandem with this demographic expansion, driving high energy use and emissions.

“If Nigeria is to achieve its emissions targets, energy efficiency must improve, other building materials must be used, and the electricity must come less from carbon-based sources,” the researchers wrote.

Currently, more than 85% of Nigeria’s electricity comes from fossil fuels, primarily natural gas. While the country benefits from oil and gas revenues, limited investment in research and education impedes progress toward energy transition goals. Nigeria aims to cut its 2015 emission levels by 20% before 2030 – a target that requires significant changes in energy sources and building practices.

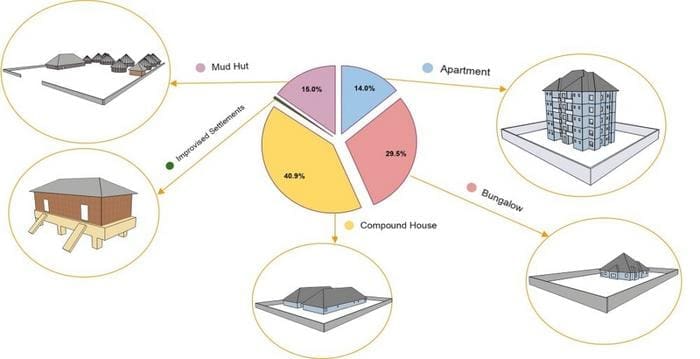

Nwagwu’s study modeled housing scenarios from 2020, accounting for an average building lifespan of 50 years. The results provide critical data on reducing emissions through alternative materials, increased energy efficiency, and a shift from carbon-heavy electricity sources.

“This is the type of information that is missing in global climate studies,” Hertwich remarked.

The project underscores the importance of fostering African expertise in climate science. Nwagwu’s contributions were supported by his role as Hertwich’s assistant during his master’s program. Now employed as a researcher at Sintef Manufacturing, Nwagwu plans to pursue a PhD, furthering research on climate solutions in Africa.

However, recent changes to Norwegian tuition policies present challenges. Students from outside the European Economic Area, including Africa, now face significant financial barriers. Hertwich emphasizes the global stakes of African climate education: “If we want to do something about the climate, we need people like Nwagwu.”

He added: “Africa’s population is growing rapidly, and what happens there will affect us all. I think we should educate both master’s and PhD students on climate protection in Africa.”

This research represents a crucial step in addressing the knowledge gap in African climate data. With more initiatives like Nwagwu’s, global climate models can become more comprehensive, aiding both African nations and the international community in tackling the climate crisis.

Journal Reference:

Chibuikem Chrysogonus Nwagwu, Sahin Akin, Edgar G. Hertwich, ‘Modelling Nigerian residential dwellings: bottom-up approach and scenario analysis’, Buildings & Cities 5, 1, 521–539 (2024). DOI: 10.5334/bc.452

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU)

Featured image: Aerial view of Osapa London, Lagos, LA, Nigeria Credit: Ben Iwara | Pexels