Ticks are crossing borders on the wings of migratory birds, potentially carrying pathogens into new regions. Rising global temperatures linked to the climate crisis are increasing the likelihood that these parasitic stowaways will survive in previously inhospitable areas, raising concerns about the spread of novel tick-borne diseases.

“If conditions become more hospitable for tropical tick species to establish themselves in areas where they would previously have been unsuccessful, then there is a chance they could bring new diseases with them,” said Dr. Shahid Karim of the University of Southern Mississippi, lead author of a new study published in Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology.

Historically, migrating birds have transported ticks across great distances, but cold climates or unsuitable habitats prevented the ticks from establishing in new locations. Now, climate-induced shifts in temperature and habitat are enabling ticks, such as the Asian long-horned tick, to thrive in new regions. This species, for instance, was first detected in New Jersey in 2017 and has since spread to 14 U.S. states.

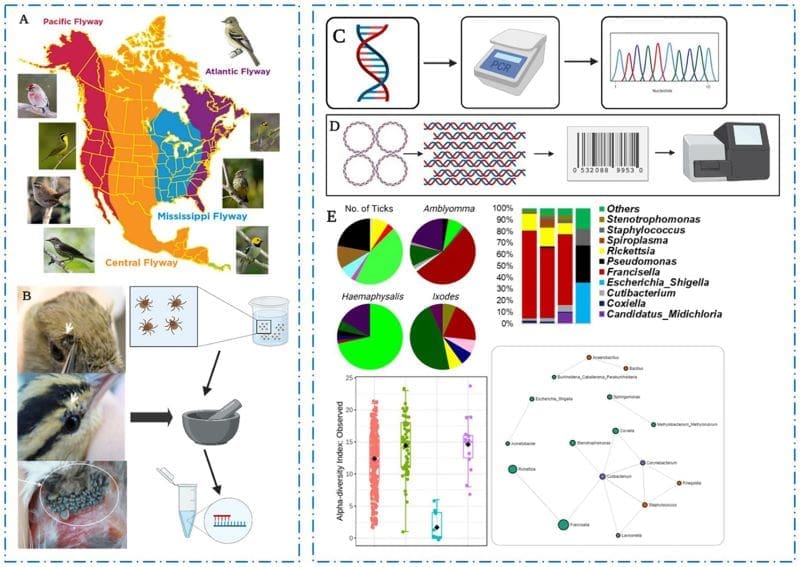

To investigate the dispersal of ticks via migratory birds, researchers set up monitoring stations along the northern Gulf of Mexico, where birds often stop to rest. The study examined nearly 15,000 birds, checking for ticks and analyzing the species collected. Birds were categorized into three groups – residents, short-distance migrants, and long-distance migrants – to map the ticks’ potential geographic origins. The researchers found that parasitism rates were relatively low, with only 421 ticks collected from 164 birds, but dispersal distances could reach up to 5,000 kilometers.

“Geographic distribution is changing very rapidly in many tick species,” said Dr. Lorenza Beati of Georgia Southern University, a co-author of the study. “For some migrating exotic ticks, global warming may create conditions at their northern destination that are similar to their usual range. If warmer climatic conditions are combined with the presence of suitable vertebrate hosts for all tick life stages, the chance of establishment is going to increase.”

The study identified 18 different tick species, four of which accounted for the majority of ticks observed. Interestingly, short-distance migratory birds carried more ticks than long-distance migrants, suggesting regional movements play a significant role in tick dispersal.

Researchers also analyzed the bacteria harbored by the ticks, focusing on species such as Francisella and Rickettsia. While Francisella bacteria appear to support ticks’ functions, Rickettsia species may have an unexplored symbiotic role, helping ticks endure the energy-intensive process of traveling on birds. However, certain Rickettsia species are also linked to diseases in humans, such as spotted fevers.

“Not only could these ticks bring new pathogens, but if they manage to establish themselves in the U.S., they could become additional vectors of pathogens already present in this country or maintain pathogens in wildlife reservoirs which can then become sources of infection,” Dr. Karim warned.

The findings highlight the need for further research to assess whether birds also act as reservoirs for tick-borne diseases when they aren’t hosting ticks. Public health precautions, such as the use of insect repellent and thorough tick checks after walking in infested areas, are recommended to mitigate risks.

Journal Reference:

Karim S, Zenzal TJ Jr, Beati L, Sen R, Adegoke A, Kumar D, Downs LP, Keko M, Nussbaum A, Becker DJ and Moore FR, ‘Ticks without borders: microbiome of immature neotropical tick species parasitizing migratory songbirds along northern Gulf of Mexico’, Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 14:1472598 (2024). DOI: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1472598

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Frontiers

Featured image credit: erik-karits-2093459 |Freepik