A small reduction in beef production among high-income nations could offer significant climate benefits, according to a new analysis.

Researchers estimate that reducing beef output by just 13% in wealthier countries could sequester 125 billion tons of carbon dioxide, an amount greater than the total global fossil fuel emissions over the past three years. This approach, they note, could transform how governments address climate challenges while also balancing food production and conservation.

The study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), suggests that by decreasing cattle production in higher-income regions, vast areas of pasture could be reclaimed for forests.

“We can achieve enormous climate benefits with modest changes to the total global beef production,” says Matthew N. Hayek, an assistant professor in New York University’s Department of Environmental Studies and lead author of the analysis. “By focusing on regions with potentially high carbon sequestration in forests, some restoration strategies could maximize climate benefits while minimizing changes to food supplies.”

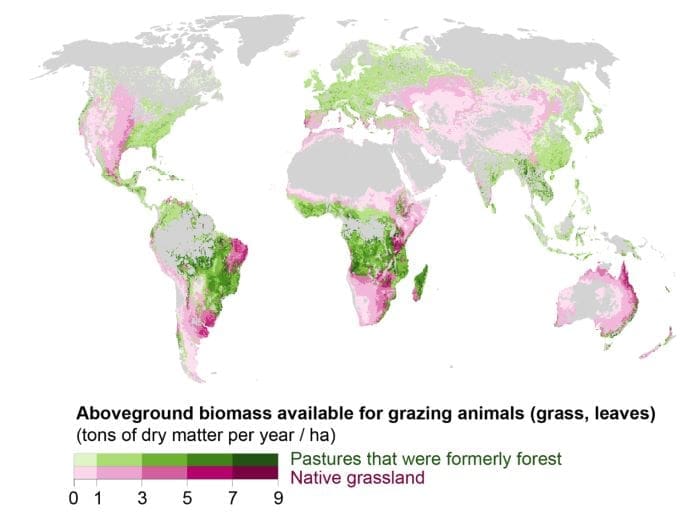

The researchers highlight the potential in converting pasturelands back to forests, which are highly effective at capturing carbon in both trees and soil. Much of this potential exists in regions that were previously forested before being cleared for livestock grazing.

By restoring these areas, carbon sequestration could increase significantly, offsetting emissions on a global scale.

Strategic reductions in high-income nations

The analysis proposes that high-income and upper-middle-income countries are ideal candidates for this shift in beef production. These areas often have pasturelands with limited grass growth per acre, making them less productive for livestock and more viable for forest restoration.

In contrast, lower-income regions, such as parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South America, typically have a longer growing season that sustains more productive grazing land, where grass can grow year-round and support higher livestock yields.

“This isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution,” emphasizes Hayek. “Our findings show that strategic improvements in the efficiency of cattle herds in some areas, coupled with decreased production in others, could lead to a win-win scenario for climate and food production.” By refining cattle-raising practices, these lower-income regions could offset minor production reductions in wealthier nations while maintaining a steady beef supply.

The study notes that eliminating grazing on all land that could naturally support forests could sequester up to 445 gigatons of CO₂ by the end of this century, equating to over a decade’s worth of global fossil fuel emissions.

“Importantly, this approach would still allow livestock grazing to remain on native grasslands and dry rangelands, which are places where crops or forests cannot easily grow,” says Hayek. “These areas support more than half of global pasture production, meaning that this ambitious forest restoration scenario would require cutting global cattle, sheep, and other livestock herds by less than half.”

Technical advancements and policy implications

To track potential pasture productivity and model the impact of beef reductions, the study relied on remote sensing technology, providing accurate data on grass growth and carbon sequestration capacity.

Johannes Piipponen, a doctoral candidate at Aalto University in Finland and co-author of the study, led this technical component.

“Even if two different areas can regrow the same amount of carbon in trees, we can now know how much pasture, hence beef production, we would have to lose in each area to grow those trees back,” Piipponen explains. He adds that the findings underscore the need for consumer awareness in high-income regions, where reducing meat consumption could benefit health as well as the climate.

The researchers also developed maps to identify areas where policies could prioritize beef reduction and support forest regrowth through targeted conservation incentives or buyouts for beef producers.

“In many places, this regrowth could occur by seeds naturally dispersing and trees regrowing without any human involvement,” says Hayek. “However, in some places, with especially degraded environments or soils, native and diverse tree-planting could accelerate forest restoration, giving regrowth a helping hand.”

The study’s authors emphasize that while ecosystem restoration alone is not a substitute for reducing fossil fuel emissions, it can play an essential role alongside traditional climate solutions.

“Within the next two decades, countries are aiming to meet critical climate mitigation targets under international agreements, and ecosystem restoration on converted pasturelands can be a critical part of that,” says Hayek. He suggests that the study’s findings could guide policymakers in addressing both climate mitigation and food security.

As nations commit to reforestation goals, the authors hope their findings can support more effective carbon sequestration strategies.

“Our study’s findings could offer paths forward for policymakers aiming to address both climate mitigation and food security concerns,” Hayek concludes. “As countries worldwide commit to ambitious reforestation targets, we hope that this research can help identify and prioritize the most effective areas for carbon sequestration efforts while considering global food needs.”

Journal Reference:

Matthew N. Hayek, Johannes Piipponen, Matti Kummu, Kajsa Resare Sahlin, Shelby C. McClelland, and Kimberly Carlson, ‘Opportunities for carbon sequestration from removing or intensifying pasture-based beef production’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121 (46) e2405758121 (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2405758121

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by New York University

Featured image credit: Pixabay | Pexels