Salton Sea dust linked to high child asthma rates

USC research highlights a worsening health crisis for children near California’s shrinking Salton Sea, where dust from the exposed lake bed is linked to high asthma rates, chronic coughs, and sleep disruption. Among the findings, 24% of local children reportedly have asthma, compared to the U.S. averages of 8.4% for boys and 5.5% for girls. This disparity particularly impacts the primarily low-income Latino/Hispanic community, with children living closest to the sea experiencing the most severe health effects.

The study attributes this health issue to dust from the exposed lake bed, or “playa,” which contains potentially toxic substances such as sulfates, pesticides, arsenic, and chromium. Air monitors revealed that local “dust events” exceeded particulate concentration levels by up to 150 micrograms per cubic meter. Research indicates that each increase in the region’s PM2.5 particle levels correlates with a rise in symptoms like wheezing and bronchitis among affected children.

Efforts to conserve water in California have paradoxically worsened the problem by accelerating the lake’s disappearance, creating new dust sources. Economic activities such as lithium mining, while offering local benefits, risk increasing the dust load further.

Jill Johnston, the study’s lead author and USC associate professor of environmental health, underscores the need for integrating public health protections into conservation and development plans: “The community has long suspected that air pollution near the sea may be impacting children’s health (…), but this is the first scientific study to suggest that children living close to the receding shoreline may experience more severe direct health impacts.”

Journal Reference: Jill E. Johnston, Elizabeth Kamai, Dayane Duenas Barahona, Luis Olmedo, Esther Bejarano, Christian Torres, Christopher Zuidema, Edmund Seto, Sandrah P. Eckel, Shohreh F. Farzan,

‘Air quality and wheeze symptoms in a rural children’s cohort near a drying saline lake’, Environmental Research 263, 2 (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.envres.2024.120070

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Southern California

Glacial AMOC: Eastern Pathway shows intensification

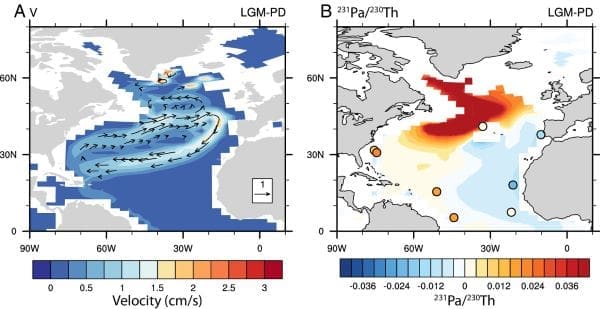

A new study reveals a substantial change in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), around 21,000 years ago.

Through sedimentary records and model simulations, researchers identified an intensified Eastern Pathway (EP) that carried Glacial North Atlantic Intermediate Water (GNAIW) from the subpolar to the subtropical North Atlantic. Unlike the present-day AMOC, where the pathway is wind-driven, this glacial-era EP was influenced by large-scale open-ocean convection in the subpolar Atlantic.

The findings challenge previous studies that characterized the glacial AMOC mainly in two dimensions and provide a clearer understanding of how glacial ocean circulation differed significantly from today. The study highlights that a more robust three-dimensional approach is necessary to accurately reconstruct past ocean circulation, offering insights into glacial climate dynamics and oceanic carbon storage.

Journal Reference: Sifan Gu, Zhengyu Liu, Hong Chin Ng, Lixin Wu et al. ‘Open ocean convection drives enhanced eastern pathway of the Glacial Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121 (45) e2405051121 (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2405051121

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by PNAS

Coral reefs may adapt to future climate – with support

Research by the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) shows that coral reefs may withstand climate-related challenges if local and global stressors are mitigated. By replicating future ocean conditions in 40 experimental systems known as “mesocosms,” researchers demonstrated that coral communities can adapt to increased temperatures and acidity over extended periods, contrary to previous projections predicting coral die-offs. This resilience, however, depends on immediate efforts to curb carbon emissions and reduce local pressures, such as pollution.

The study’s experimental approach included multiple coral species and organisms from Hawaiian reefs, making it one of the most comprehensive examinations of reef adaptability under climate change.

Lead author and HIMB post-doctoral researcher Christopher Jury notes: “By understanding how these species respond to climate change, we should have a better understanding of how Hawaiian reefs and other Indo-Pacific reefs will change over time.” These findings emphasize the importance of realistic conservation practices, including biodiversity-focused strategies to support coral health and persistence.

Journal Reference: Christopher P. Jury, Keisha D. Bahr, Annick Cros,Robert J. Toonen et al. ‘Experimental coral reef communities transform yet persist under mitigated future ocean warming and acidification’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121 (45) e2407112121 (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2407112121

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Hawaiʻi

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay