Recent research by scientists from the Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon has revealed that bottom trawling in the North Sea is significantly undermining the seabed’s ability to store carbon, releasing it into the water and the atmosphere in the form of carbon dioxide (CO2). This alarming finding, part of the collaborative APOC project, highlights the global implications of intensive bottom fishing on the ocean’s carbon sequestration capabilities.

The study, published in Nature Geoscience, emphasizes the need for more comprehensive protective measures for vulnerable marine environments.

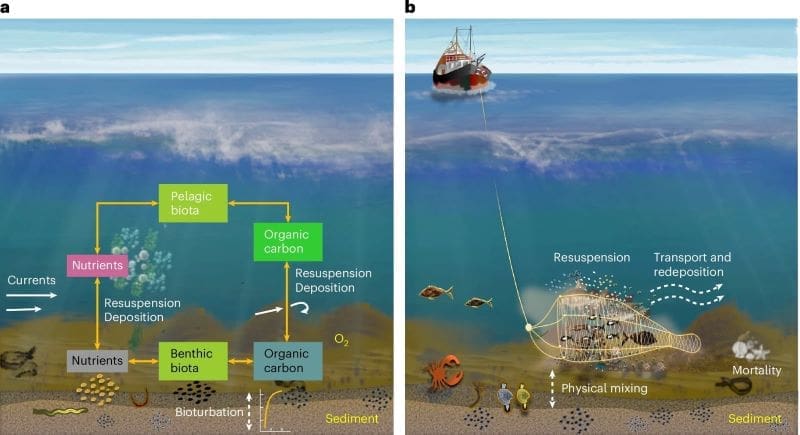

Trawling, a method of dragging nets across the seabed to catch species like flatfish and shrimp, disrupts the sediment that naturally acts as a carbon sink. According to the lead researcher, Dr. Wenyan Zhang, sediment samples from heavily trawled regions were found to contain significantly less organic carbon than those from areas with less fishing activity.

“We were able to attribute this effect to bottom trawling with high confidence,” said Dr. Zhang, adding that their findings offer a more accurate assessment of the impact at both regional and global levels. The researchers used advanced computer models to simulate the effects of trawling over several decades, revealing a continuous decline in the carbon content of soft, muddy seafloor areas, which are particularly vulnerable.

Trawling releases millions of tons of CO2

Seafloor sediments are essential for long-term carbon storage. Carbon absorbed into the seabed is normally consumed by animals and, through their movements, pushed deeper into the sediment where it can be stored for thousands of years. However, trawling disrupts this process by stirring up the sediments, leading to the destruction of habitats and the death of marine species.

When sediment is brought into contact with oxygenated water, microorganisms such as bacteria convert the carbon into CO2, which then escapes into the atmosphere, exacerbating global warming.

The study estimates that bottom trawling in the North Sea alone releases approximately one million tons of CO2 annually. On a global scale, trawling is responsible for releasing 30 million tons of CO2 from sediments each year. Although this figure is lower than previous estimates, it remains substantial.

The new model developed by the researchers considers previously overlooked feedback loops involving sediment particle dynamics and marine life on the seafloor, offering a more nuanced understanding of the carbon impacts of trawling.

The research underscores the urgent need to protect muddy seabeds, which are critical for carbon storage. Marine conservation efforts have traditionally focused on protecting hard, sandy areas and reef ecosystems, which are ecologically diverse but store far less carbon compared to soft, sedimentary regions.

“Our results point to the need for special protection of muddy habitats in marginal seas such as the North Sea,” Dr. Zhang noted.

In light of these findings, there is a growing call for policy reforms aimed at enhancing marine spatial planning and conservation. Restricting or eliminating bottom trawling in carbon-rich areas could significantly contribute to reducing CO2 emissions, offering a climate benefit in addition to preserving marine biodiversity. Dr. Zhang suggested that their research methods could be instrumental in optimizing future marine protection policies.

The APOC project: a collaborative effort

The study is part of the Anthropogenic Impacts on Particulate Organic Carbon Cycling in the North Sea (APOC) project, coordinated by the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) and the Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon. The project, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), aims to assess the long-term impacts of human activities and climate change on carbon storage in the North Sea.

By analyzing over 2,300 sediment samples, the researchers provided a clearer picture of how bottom trawling alters the carbon cycle in coastal ecosystems, which play a crucial role in regulating global carbon levels.

As global efforts to combat climate change continue, this study adds to the growing body of evidence that human activities in marine environments have far-reaching consequences. By highlighting the detrimental impact of bottom trawling on carbon storage, the research makes a compelling case for rethinking fishing practices and strengthening marine conservation efforts to mitigate the effects of climate change.

Journal Reference:

Zhang, W., Porz, L., Yilmaz, R. et al. ‘Long-term carbon storage in shelf sea sediments reduced by intensive bottom trawling’, Nature Geoscience (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-024-01581-4

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres

Featured image credit: Mike van Schoonderwalt | Pexels