PLOS | MP – Fossils dating back over 600,000 years have uncovered key insights into how Southern Europe’s ecosystems adapted to dramatic climate changes, according to a new study published in PLOS ONE.

Led by Beniamino Mecozzi of Sapienza Università di Roma, the research highlights the effects of glacial-interglacial cycles on the region’s fauna. The findings illustrate the complex interplay between species survival and environmental conditions, showing that animal communities responded to alternating cold and warm periods with significant shifts in biodiversity and habitat use.

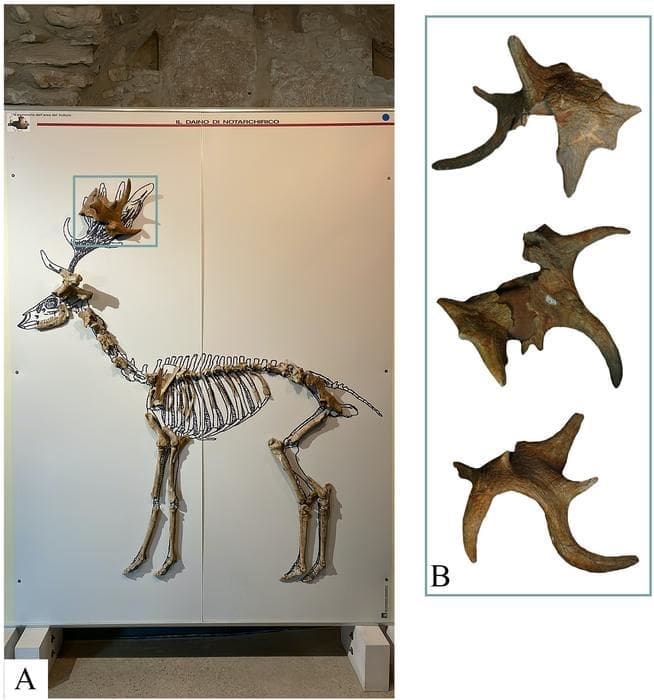

The Notarchirico site has long been valued as a source of information on the Early-Middle Pleistocene, with fossils stretching from around 695 thousand to 614 thousand years ago. The authors of the present study examined mammalian fossils at the site and how they might correlate with climate conditions over time.

The researchers note that the earliest era documented at Notarchirico corresponded with a relatively warm period, complete with fossil evidence of genera such as hippos (Hippopotamus) and rhinos (Stephanorhinus), as well as deer and macaque monkeys — demonstrating that the area likely had woods, steppes and lakes or ponds.

But by around 660 thousand years ago, the macaques and hippos, both warm weather animals, had vanished. The mammal community had shifted to one dominated by the straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus), and cattle-like animals such as the Pleistocene wood bison (Bison schoetensacki), with relatively few deer. This indicates that the area was likely more open, with fewer forests, and representative of a colder climate, as this period is believed to have had some of the Pleistocene’s most extensive glaciation.

Fossils from the upper levels of the deposit documented at Notarchirico include a lot of deer who ate from woody shrubs and trees, indicating that the climate had likely warmed again and the area had filled in with forests.

In addition to reflecting the changing climate of the time, the fossil evidence at Notarchirico provides more insight into how and when different species moved out of and into Europe during the Pleistocene. Fossils recovered on site include some of the oldest known evidence in all of Europe of the straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus) and the red deer (Cervus elaphus), as well as some of the oldest known evidence of the cave lion (Panthera spelaea) in southwestern Europe.

The authors add: “The results of this work highlight the importance of resuming excavation and research activities at sites that were excavated in the past, as well as revisiting old museum collections that are often forgotten. By integrating the review of paleontological collections gathered in the past with the study of unpublished materials from new research, it has been possible to observe how terrestrial ecosystems responded to nearly 100,000 years of climate change.“

“The work published here is part of the new research project LATEUROPE, coordinated by Dr. Marie Hélène Moncel, with permission from the Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio of Basilicata, Direzione Regionale Musei Basilicata, and Musei e Parchi Archeologici di Melfi e Venosa, which also include the study of collections preserved at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale ‘Mario Torelli’ and the Parco Paleolitico di Notarchirico.”

Journal Reference:

Mecozzi B, Iannucci A, Carpentieri M, Pineda A, Rabinovich R, Sardella R, et al. ‘Climatic and environmental changes of ~100 thousand years: The mammals from the early Middle Pleistocene sequence of Notarchirico (southern Italy)’, PLoS ONE 19(10): e0311623 (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0311623

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by PLOS

Featured image credit: Jesús Gamarra 2023 | CC BY 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons (Source: Jan van der Made et al. | DOI: 10.1007/s12520-023-01734-3)