For the past 25 years, the Alfred Wegener Institute has operated a long-term observatory in the Arctic deep sea: the HAUSGARTEN. Located between Greenland and Svalbard, it is where researchers investigate natural and climate-change-related changes in a polar, marine ecosystem – from the ocean’s surface to the seafloor, 5,500 metres below. Many of the observatory’s stations are located below the sea ice, while its autonomous systems take measurements year-round, i.e., even when left unmanned.

A garden sheltered from the neighbours’ prying eyes is something that likely many of us wouldn’t mind having. The fact that the garden’s beauty can only be seen using advanced technologies is the challenge you have to accept when the Arctic deep sea is your destination of choice. 25 years ago, experts from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) rose to precisely this challenge by creating an observatory between Greenland and Svalbard, which has been called the HAUSGARTEN ever since. At the end of this week, the research icebreaker Polarstern will depart on the next expedition to it.

“In a 1999 Polarstern expedition, we had the deep-sea robot Victor 6000 from Ifremer (Institut Française de Recherche pour l´Exploitation de la Mer) on board and used it to map the seafloor and select the location for what is now the central station,” say AWI biologists Dr Thomas Soltwedel and Dr Michael Klages, recalling the very beginning. “During a journey to our cooperation partners in France, we came up with the name HAUSGARTEN, which was meant to emphasize our intention to pursue a long-term research plan.” The fact that, ever since, biologists, oceanographers, geochemists and technicians leave every year to do some “gardening” shows just how well the name was chosen.

In the expedition report for Polarstern Expedition ARK-XV/1 from 1999, you can read the following: “Major objectives for the two first sites will be to carry out pre-site surveys (large-scale photo/video observations and additional sampling of organisms and sediments) to establish a ‘long-term benthic station’ in the deep Arctic Ocean. Scientific background is the multi-disciplinary approach to assess seasonal and inter-annual variabilities in various physical, geological/geochemical and biological parameters, and to evaluate interactions between gradients of these parameters at different temporal and spatial scales in the arctic deep-sea.”

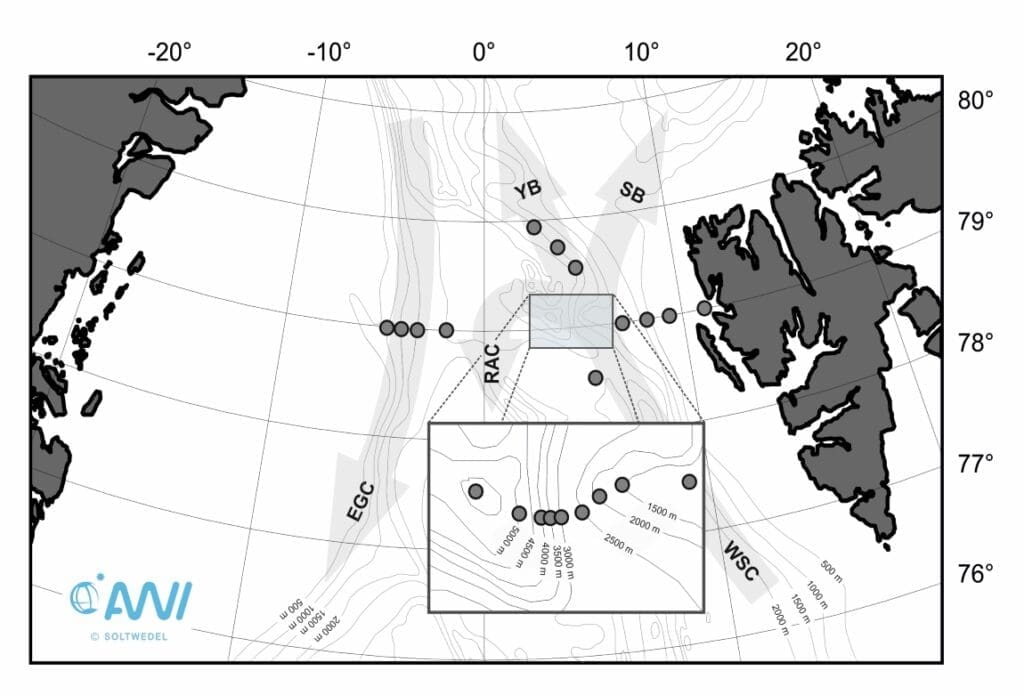

Over the years, 21 stations at depths ranging from 250 to 5,500 metres were set up, which the Polarstern regularly visits. Today, the HAUSGARTEN is also part of the FRAM infrastructure, which provides data on Earth system dynamics, climate variability, and attendant changes in the ecosystem. All year round, autonomous monitoring systems, some of which are located below the sea ice, record essential data like temperature, salinity and ocean currents, but also the activity of microorganisms, plankton and benthos. From the outset, the export of organic material from the surface to the deep sea has been an important aspect. Organisms living there depend on food sinking down from the sea surface, since the light needed for photosynthesis-based plant growth and therefore primary production cannot penetrate the depths. The HAUSGARTEN’s central station, at a depth of 2,500 metres in the eastern Fram Strait, serves as a test area for unique in-situ biological experiments on the ocean floor, in which various scenarios are simulated under changing environmental conditions.

The ocean is one of the largest carbon sinks on our planet. This is due in part to the biological carbon pump: just below the water’s surface, microorganisms like bacteria and phytoplankton absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis. When their bodies sink to the ocean floor, the carbon they contain can be stored there for several thousand years. Using data from the HAUSGARTEN, AWI researchers deciphered how meltwater from drifting sea ice is changing the effectiveness of the biological carbon pump and when atmospheric carbon is absorbed and stored.

A further study investigated the links between biodiversity and ecosystem functions, as well as their connection to environmental factors, by analysing the biological characteristics of benthos communities. Generally speaking, the functional structure of biotic communities in Fram Strait follows a gradient that depends on food availability, and the researchers concluded: “Given the connections between the sea ice, primary production in the surface water, and the availability of food at the seafloor, our findings indicate that benthic organisms will be sensitive to the predicted anthropogenic environmental fluctuations in the polar regions. If the environmental conditions change, it can be expected that the functions of the benthic ecosystem will change as well.”

In addition, Atlantic influences on the Arctic Ocean are a research focus, as the Arctic is warming much faster than other regions in response to climate change. Polar zooplankton species not only have to cope with rising water temperatures; they also have to contend with stiffer competition in the form of boreal-Atlantic sister species, which are finding their way into the Arctic Ocean through the increased inflow from the Atlantic. Temperature experiments conducted on board the Polarstern during HAUSGARTEN expeditions revealed that some Arctic copepod species displayed greater physiological tolerances to the warming of the ocean than expected. However, in areas with significantly overlapping distribution ranges, from a certain threshold temperature they could be displaced by their Atlantic counterparts. As such, the “Atlantification” of the Arctic zooplankton community would seem to depend more on ecological interactions than on physiological limitations.

For more than a decade now, research into marine litter has been another important aspect. For example, the Ocean Floor Observation and Bathymetry System (OFOBS), developed at the AWI, films and photographs the seafloor at regular intervals. Analysis of the footage shows that anthropogenic litter can increasingly be found even in the Arctic deep sea.

The Polarstern is scheduled to leave her homeport in Bremerhaven at the end of this week. Between two roughly four-week-long expeditions to the HAUSGARTEN, the ship will call to port in Tromsø, Norway, to change out the research teams. In early August, the icebreaker will set course for the Central Arctic and is expected back in Bremerhaven by mid-October.

More information: The Alfred Wegener Institute pursues research in the polar regions and the oceans of mid and high latitudes. As one of the 18 centres of the Helmholtz Association it coordinates polar research in Germany and provides ships like the research icebreaker Polarstern and stations for the international scientific community. Alfred-Wegener-Institut – Press Release; Featured image: Polarstern in AWI-Hausgarten Credit: Mario Hoppmann