Summary:

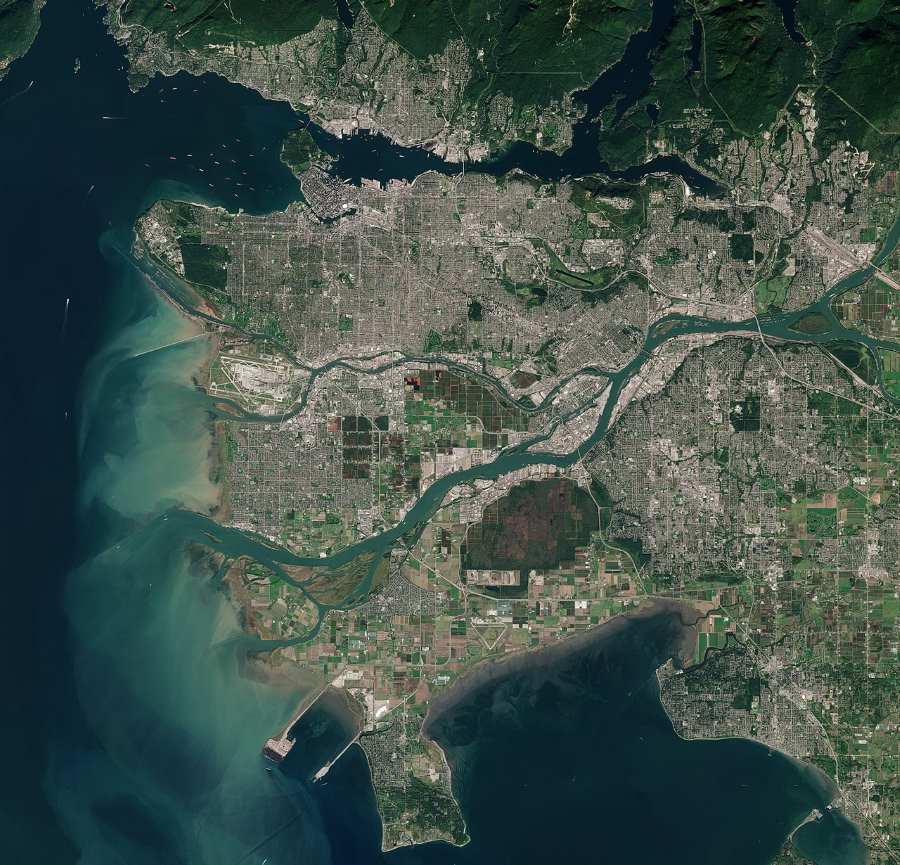

British Columbia’s local governments are falling short in preparing for extreme heat, according to new research from Simon Fraser University. Drawing on more than 240 official documents from 27 municipalities and two regional districts, the study evaluated how jurisdictions in Metro Vancouver and the Fraser Valley are planning for rising temperatures. It found significant variation in heat response strategies, with larger, wealthier cities like Vancouver, Surrey, and New Westminster taking more initiative, while areas such as Chilliwack, Delta, and Port Coquitlam showed limited planning.

Published in the Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, the study identified urban greening — such as parks and tree planting — as the most common mitigation approach, largely due to broad public support. However, many communities lacked clear strategies to address heat risk, and few plans showed coordination across jurisdictions or alignment with higher levels of government.

Lead author Andréanne Doyon, associate professor at SFU’s School of Resource and Environmental Management, emphasized the urgency: “We have to take steps today to prepare our buildings and neighbourhoods so we can save lives tomorrow.” Doyon launched the research following the 2021 heat dome, which claimed over 600 lives in B.C. The study calls for stronger regional cooperation and long-term urban planning to prevent future tragedies.

Prepare today to save lives tomorrow: SFU study finds gaps in B.C. extreme heat response plans

Local authorities must do more to prepare communities in British Columbia for the dangers of extreme heat, according to a new research paper from Simon Fraser University.

Four years after the infamous 2021 heat dome, which killed more than 600 people in B.C. alone, the ground-breaking study found significant differences in how municipalities within the Metro Vancouver and Fraser Valley regional districts are preparing for heat events.

While municipalities with larger populations and more financial resources are generally taking greater steps to mitigate the dangers of heat, the research found there are fewer urban planning initiatives in areas with a lower socio-economic status or lower population density.

Vancouver, Surrey and New Westminster led the way with the highest number of initiatives. Chilliwack, Delta, Port Coquitlam and West Vancouver were among those with limited plans.

“Heat is a growing danger for people around the world. The science shows that global temperatures are rising and extreme heat events are going to become more intense and more frequent,” says Andréanne Doyon, associate professor at SFU’s School of Resource and Environmental Management.

“In B.C., we have seen firsthand the tragic consequences of extreme heat. We have to take steps today to prepare our buildings and neighbourhoods so we can save lives tomorrow.”

Doyon applied for a grant to carry out the research following the 2021 heat dome. The study analysed more than 240 official documents, dating from 2023, from 27 municipalities and two regional districts.

The researchers looked at key terms relating to heat to assess if plans are being put in place, and if so, what are the steps being taken to mitigate the dangers.

Initiatives were then grouped into three main areas to determine the nature the response: urban greening, urban design and land use. It is the first time an analysis of heat mitigation strategies across local governments in B.C. has been carried out.

“We wanted to know what is being done at local and regional levels so we could form a baseline and look for opportunities to improve initiatives,” says Doyon, who holds a Ph.D. in urban planning.

“We found that the level of attention being given to heat mitigation strategies varies significantly depending on where you live. There are a lot of factors behind this variation, such as financial constraints, lack of staff expertise within authorities, population density or simply politics.”

The report also found there is a need for more co-operation across jurisdictions.

“We need to see a greater focus on how we improve neighbourhoods in their entirety, rather than isolated initiatives,” says Doyon.

“Better co-operation and co-ordination across authorities will lead to more effective action. Local governments can learn from each other, while planning agencies can play a significant role in bringing extreme heat strategies into the mainstream.”

Urban greening was found to be the most common heat mitigation response, which is unsurprising according to Doyon, as there is greater public understanding and support for green spaces such as parks and trees in urban areas.

“Where I’m worried is that Metro Vancouver has lost hundreds of square kilometers of ecological space, primarily due to development,” she adds.

“We can’t keep doing that. Those green spaces help to keep our neighbourhoods cool.”

As part of the next step in the research, Doyon and her team are carrying out an in-depth study on housing policy in Burnaby, one of the areas hardest hit, in terms of fatalities, by the 2021 heat dome.

Journal Reference:

Chenne, W., & Doyon, A., ‘How are local governments planning for heat mitigation? A study of Metro Vancouver and Fraser Valley jurisdictions’, Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 1–14 (2025). DOI: 10.1080/1523908X.2025.2480691

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Simon Fraser University

Featured image credit: Lee Robinson | Unsplash