How Australia’s hottest capital city is confronting the challenges of dealing with heat in a warming climate might offer solutions for the world.

By Stephen Cook, Tim Muster and Natthanij Soonsawad | CSIRO in Darwin

Table of Contents

Darwin is arguably Australia’s most dramatic example of the need for city planners to adapt to a warming climate and deal with the health risks that poses for residents, particularly the socially disadvantaged.

Measures that can reduce the impact of extreme heat in a warming climate are more than a matter of comfort — they can make a life-and-death difference.

Extreme heat accounts for more fatalities than all other natural disasters in Australia combined and the number of people living in tropical areas vulnerable to heat is growing so rapidly that the tropics will house about half the world’s population by 2050.

Decision-makers in the nation’s hottest capital city recognised that need — to create a cooler, more liveable city — and the lessons learned in Darwin offer hope to other cities trying to adapt and become climate-resilient.

Along the way, effective action can improve liveability; cut the cost of cooling where people live and work; bring other environmental benefits, such as reduced emissions from air conditioning; and help the vulnerable who are most exposed to heat health impacts.

Why Darwin?

Adapting cities to a warming climate is paramount in tropical zones that are experiencing rapid urban population growth. Lessons learnt in adapting to heat in Darwin can help guide actions to reduce vulnerability in other tropical cities.

Located in Australia’s wet-dry tropics, it experiences a hot year-round climate where summer temperatures regularly exceed 35 degrees Celsius, which is moderated in the dry season by reduced humidity and lower overnight temperatures.

However, during the build-up to the monsoon, which typically breaks in late December, high humidity and high temperatures create extreme heat risks.

These conditions are more pronounced in the city due to what is known as the urban heat island effect, where buildings, roads and other urban structures absorb and retain heat, which is then emitted at night.

Decision-makers, planners and researchers in Darwin recognised they needed to create a cooler and more liveable city.

Real-world testing

The Darwin Living Lab — known colloquially as The Lab — was established to support the transition to a more liveable, resilient and sustainable city.

Such urban living labs recognise that addressing complex challenges in cities requires collaboration across different levels of government, sectors and the community.

The Lab allows accelerated innovation and testing of heat mitigation approaches, as well as providing the science and technology needed to support decision-makers navigating change.

The Lab also has a web app that allows Darwin residents to zoom in on their suburb and assess their own heat exposure and find solutions to help mitigate it, like planting more trees around their homes or painting their roof a lighter colour.

The first stage of The Lab was the co-development of a heat mitigation strategy, Feeling Cooler in Darwin (.pdf), that identified priority actions for a cooler city.

Heat-mitigation planning in cities needs to take in the connections across private and public spaces in both indoor and outdoor environments as well as urban density and land use.

Public open spaces, including street verges, can often accommodate higher tree canopy cover than other urban land.

Heat mapping of Darwin also demonstrates the importance of blue infrastructure — essentially water features like ponds — in cooling the city.

The creation of blue-green corridors throughout the city can cool through increased shade and evapotranspiration — the evaporation and release of water by plants.

Urban design that encourages breeze flow can reduce the urban heat island effect by helping to remove heat and passively cool buildings that reduces the need for air conditioning.

Cutting the heat

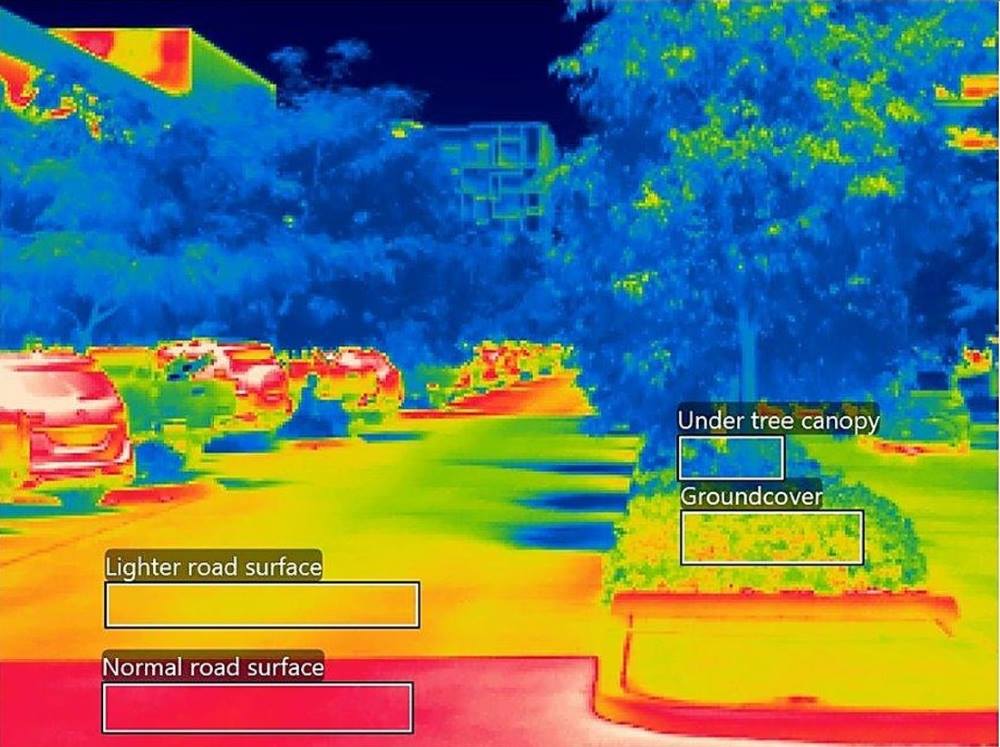

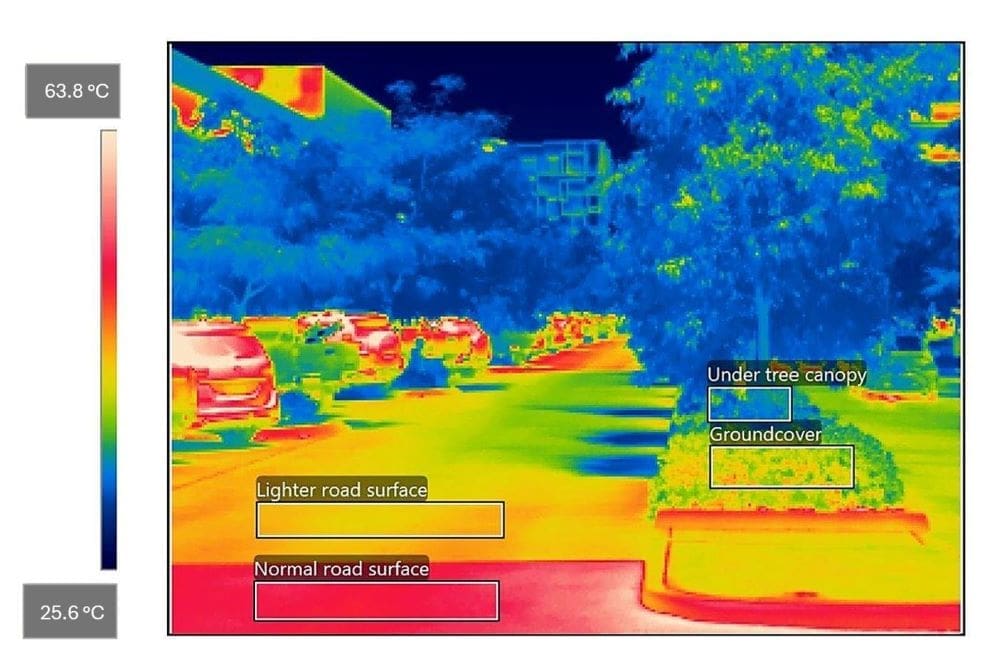

Options to reduce the heat island effect, which increases radiant heat from surfaces, need to be considered at the local, even neighbourhood scale.

Any potential action needs to consider the energy and water requirements.

Darwin households use twice as much water as most other Australian capital cities, largely driven by irrigation demand in the long dry season.

Tree planting that prioritises drought resilient species that don’t need as much water can provide more cooling benefits than irrigated grass.

Healthy green grass areas reduce heat island effects compared with paved surfaces but green groundcover does not reduce the radiant heat people experience from direct sun exposure so it makes only a marginal contribution to outdoor thermal comfort at the hottest times of the day.

Lighter-coloured materials are more reflective and generally absorb and store less heat. Using reflective materials for roofs and roads can reduce peak temperatures and help lower household cooling costs.

Yet even those actions have side effects — the use of heat-reflective coatings for unshaded footpaths can also increase the reflection of radiant heat back to pedestrians during the middle of the day so maximising shade in these areas is a focus.

Using mature trees, while effective for shade and improved air quality, is not always feasible in densely populated parts of the city.

To get around that, Darwin has built shade structures covered with climbing plants that have been shown to improve thermal comfort — or how comfortable people feel in their environment, ideally neither too hot or too cold — by up to 5 degrees Celsius and reduce land surface temperature by about 20 degrees.

Trees in new suburbs

The variation in tree canopy cover between more established Darwin suburbs and new growth corridors shows up in distinct differences in the heat pattern.

Many established suburbs, typically larger lots where the buildings take up about 25 percent of the land, have an average tree canopy coverage of about 30 percent. These suburbs are generally cooler.

The prevalence of heat-retaining land surfaces and lower tree canopy cover in new growth areas drives higher land surface temperatures.

They are typically smaller lots where the building takes up nearly half the land area and additional driveways and paving leave less area for establishing tree canopy cover, which is just five percent of the lot on average.

That shift to denser urban development means there’s a need for innovative public open space design that achieves high tree canopy cover with a mix of native and exotic tree species that can provide usable shade while considering biodiversity and other benefits.

The cost of cooling

Darwin pays for its hot climate because it pays more to cool buildings compared with other Australian cities.

A typical Northern Territory household consumes about 8,500 MWh of energy each year — almost double that of a typical household in New South Wales — and more than half of it goes on cooling.

Most households in Darwin rely on air conditioning to cool homes and businesses, particularly during the hot and humid build-up season.

This leaves disadvantaged groups vulnerable to heat health risks, given they are more likely to live in poorer housing and cannot afford the cost of air conditioning.

This is where the use of passive design in homes can reduce the time an air conditioner is required, which means even electricity grid outages are less likely to be so disruptive or even impact health.

Passive design can reduce the need for air conditioners and the power bills that come with them by up to 40 percent. It might include shading of the house, particularly windows, to reduce solar gain through using trees, outdoor blinds, extended eaves and shade structures.

All of these strategies provide ways to help keep our cities liveable, sustainable and resilient into the years ahead as we cope with the challenges of a warming climate.

***

Stephen Cook is an environmental scientist with a background in spatial planning whose research focuses on climate adaptation in cities. Mr Cook is the local coordinator of the Darwin Living Lab.

Dr Tim Muster is a principal research scientist whose research focuses on cities as complex systems. Dr Muster leads CSIRO’s Urban Living Lab initiative, including the Darwin Living Lab and Sydney Science Park, which seeks to build a portfolio of urban innovation precincts that progress an agenda of place-based experimentation and learning.

Dr Natthanij Soonsawad is an environmental research scientist with a background in ecology and environmental planning. Dr Soonsawad’s research explores urban planning, the sustainable use of ecosystem services, and their role in alleviating environmental degradation and building adaptive capacity to cope with climate change impacts.

The Darwin Living Lab is a 10-year CSIRO-led collaboration with the City of Darwin and Northern Territory and Australian governments established under the Darwin City Deal.

A wide range of researchers from CSIRO and partner organisations have contributed to Darwin Living Lab projects. In particular, CSIRO’s Dr Raymundo Marcos Martinez who led the development of the heat mitigation app.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by 360info

Featured image credit: Supplied by CSIRO Environment | CC BY 4.0