Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press daily roundup, featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

New study validates lower limits of human heat tolerance

A study from the University of Ottawa’s Human and Environmental Physiology Research Unit (HEPRU) has confirmed that the limits for human thermoregulation — our ability to maintain a stable body temperature in extreme heat — are lower than previously thought.

This research, led by Dr. Robert D. Meade, former Senior Postdoctoral Fellow and Dr. Glen Kenny, Director of HEPRU and professor of physiology at uOttawa’s Faculty of Health Sciences, highlights the urgent need to address the impacts of climate change on human health.

The study found that many regions may soon experience heat and humidity levels that exceed the safe limits for human survival. “Our research provided important data supporting recent suggestions that the conditions under which humans can effectively regulate their body temperature are actually much lower than earlier models suggested,” states Kenny. “This is critical information as we face increasing global temperatures.”

Utilizing a widely used technique known as thermal-step protocols, Meade and his team exposed 12 volunteers to various heat and humidity conditions to identify the point at which thermoregulation becomes impossible. What made this study different, was that participants returned to the laboratory for a daylong exposure to conditions just above their estimated limit for thermoregulation.

Participants were subjected to extreme conditions, 42°C with 57% humidity, representing a humidex of approximately 62°C. “The results were clear. The participants’ core temperature streamed upwards unabated, and many participants were unable to finish the 9-hour exposure. These data provide the first direct validation of thermal step protocols, which have been used to estimate upper limits for thermoregulation for nearly 50 years,” says Meade.

“Our findings especially timely, given estimated limits for thermoregulation are being increasingly incorporated into large scale climate modelling” explains Meade. “They also underscore the physiological strain experienced during prolonged exposure to extreme heat, which is becoming more common due to climate change.”

The implications of this research extend beyond academia. As cities prepare for hotter summers, understanding these limits can help guide health policies and public safety measures. “By integrating physiological data with climate models, we hope to better predict and prepare for heat-related health issues,” adds Kenny.

As the world grapples with the realities of climate change, this research aims to spark important conversations about our safety and adaptability in increasingly extreme environments.

Journal Reference:

R.D. Meade, F.K. O’Connor, B.J. Richards, E.J. Tetzlaff, K.E. Wagar, R.C. Harris-Mostert, T. Egube, J.J. McCormick & G.P. Kenny, ‘Validating new limits for human thermoregulation’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122 (14) e2421281122 (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2421281122

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Ottawa

New warnings of a ‘Butterfly Effect’ — in reverse

A Yale-led study warns that global climate change may have a devastating effect on butterflies, turning their species-rich, mountain habitats from refuges into traps.

Think of it as the ‘butterfly effect’ — the idea that something as small as the flapping of a butterfly’s wings can eventually lead to a major event such as a hurricane — in reverse.

The new study, published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, also suggests that a lack of comprehensive global data about insects may leave conservationists and policymakers ill-prepared to mitigate biodiversity loss from climate change for a wide range of insect species.

For the study, a team co-led by Yale ecologist Walter Jetz analyzed phylogenetic and geographic range data for more than 12,000 butterfly species worldwide. The team was also co-led by Stefan Pinkert, an entomologist at the University of Marburg, in Germany, and former postdoctoral associate at Yale.

They found that butterfly diversity is highly clustered in tropical and subtropical mountain systems: two-thirds of butterfly species live primarily in the mountains, which contain 3 1/2 times more butterfly hotspots than lowlands.

Yet those mountain ecosystems — and surrounding areas — are quickly changing as a result of climate change. According to the study, 64% of the temperature niche space of butterflies in tropical areas will erode by 2070, with the geographically restricted temperature conditions of mountains constantly shrinking.

“The diversity, elegance, and sheer beauty of butterflies impassion people worldwide,” said Jetz, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences and director of the Yale Center for Biodiversity and Global Change (BGC Center).

“Co-evolved with host plants, butterflies form an integral part of an ecologically functioning web of life,” he added. “Unfortunately, our first global assessment of butterfly diversity and threats finds that butterflies’ fascinating diversification into higher-elevation environments might now spell their demise, with potentially thousands of species committed to extinction from global warming this century.”

Pinkert, a former postdoctoral researcher at the BGC Center, added: “As an entomologist, I am committed to informing the public about the distribution of insect diversity and targeted ways to protect it. Our results are insightful from an ecological point of view but unfortunately also very alarming.”

Current priorities in biodiversity preservation, the researchers note, are geared to animals and plants, rather than insects. Until now, a global assessment of the geographic coincidence of diversity, rarity, and climate change threats for an insect system did not exist.

The new assessment reveals that patterns in butterfly diversity differ strongly from those of much better studied groups such as birds, mammals, and amphibians — challenging the relevance of existing conservation priorities, the researchers said.

“This research was made possible by many years of mobilizing various global data and newly developed integrative approaches, all aimed at filling this critical information gap for at least one insect taxon,” Pinkert said.

Jetz said he hoped the new study — and future research enabled by the Map of Life, a global database, directed by Jetz, that tracks the distribution of known species worldwide — will support conservation managers to include insects in their plans for biodiversity preservation.

“A reduction of carbon emissions, combined with proactive identification and preservation of key butterfly habitats and migratory corridors, will be key to ensuring that much of butterfly diversity survives to benefit future generations,” Jetz said.

Co-authors of the study are Nina Farwig of the University of Marburg and Akito Kawahara of the University of Florida.

The research was supported, in part, by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation.

To explore more of the results of the research at the Map of Life site, visit here.

Journal Reference:

Pinkert, S., Farwig, N., Kawahara, A.Y. et al., ‘Global hotspots of butterfly diversity are threatened in a warming world’, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-025-02664-0

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Jim Shelton | Yale University

‘Unprecedented’ recent floods swamped by previous highs

A team of scientists – led by the University of Exeter – used geological palaeo-flood records to examine extreme floods in western Europe over several thousand years.

The study finds many previous floods exceeded recent extremes, highlighting the need to use these palaeo records – not just river gauge data that typically exists for the last century or less.

The researchers challenge the idea that recent floods can be attributed solely to greenhouse gas emissions, but they warn that the combination of natural extremes and global warming could lead to truly extraordinary floods.

“In recent years, floods around the world – including in Pakistan, Spain and Germany – have killed thousands of people and caused enormous damage,” said Professor Stephan Harrison, from the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Exeter’s Penryn Campus in Cornwall.

“Such floods are seen as ‘unprecedented’ – but if you look back over the last few thousand years, that’s not the case.

“In fact, floods we call unprecedented may be nowhere near the most extreme that have happened in the past.”

Palaeo-flood records use a range of evidence including floodplain sediments, dating sand grains and past movement of boulders to identify past extremes.

Professor Harrison added: “You need that knowledge of the past if you’re going to understand the present and make predictions about the future.

“Coupling evidence of past extremes with the extra pressure now being added by human-caused global warming – which causes more extreme weather – you see a risk of genuinely unprecedented floods emerging.”

Projects such as housing and infrastructure are built to be resilient to extreme floods – based on assumptions such as a “one-in-200 year” or “one-in-400 year” flood event.

“If we rely on relatively short-term records, we can’t say what a ‘one-in-200 year’ flood is – and therefore our resilient infrastructure may not be so resilient after all,” said Professor Mark Macklin.

“This has profound implications for flood planning and climate adaptation policy.”

The study examined palaeo-flood records for the Lower Rhine (Germany and Netherlands), the Upper Severn (UK) and rivers around Valencia (Spain).

In the Rhine, records for about 8,000 years show at least 12 floods that are likely to have exceeded modern peaks.

The Severn analysis shows that floods in the last 72 years of monitoring are not exceptional in the context of palaeo-flood records of the last 4,000 years.

The largest flood in the Upper Severn occurred in about 250 BCE and is estimated to have had a peak discharge 50% larger than the damaging floods in the year 2000.

Journal Reference:

Harrison, S., Macklin, M.G., Toonen, W.H.J. et al., ‘Robust climate attribution of modern floods needs palaeoflood science’, Climatic Change 178, 71 (2025). DOI: 10.1007/s10584-025-03904-9

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Alex Morrison | University of Exeter

The trajectory of wetland change in China between 1980 and 2020: Hidden loss and restoration effects

This study is led by Prof. Dehua Mao and Prof. Zongming Wang (Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences).

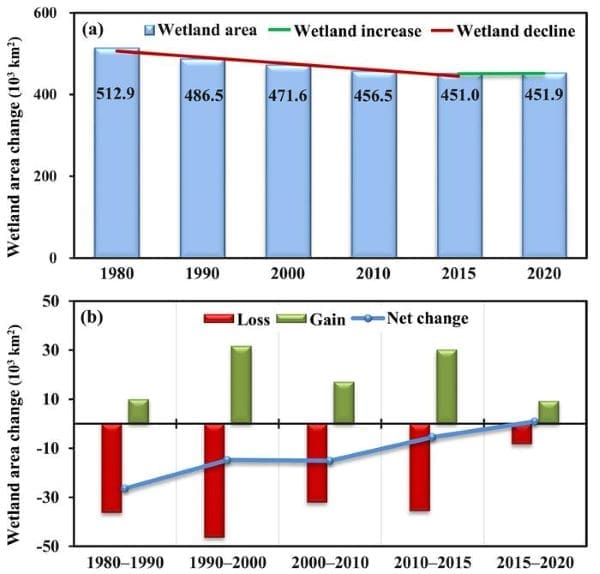

Although it looks like a simple data analysis, researchers prepared this work and generated the wetland product over five years. The hybrid object-based and hierarchical classification approach was applied to over 53,000 scenes of Landsat images acquired between 1980 and 2020 and to create a national wetland mapping product (China_Wetlands) for six periods (e.g., 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, 2015, and 2020).

Moreover, based on the China_Wetlands, they exhibits diverse Chinese wetland changes, and presents their trajectory in response to climate change and human impacts in the past four decades.

“I think it’s a great work,” Prof. Yeqiao Wang (University of Rhode Island) says.

There was a substantial wetland shrinkage in area before 2015, with a small rebound between 2015 and 2020. The net loss was ~60.9 × 103 km2, 12% of the area in 1980. Although this area value looks like small, we must see the hidden loss of wetlands. The loss of natural wetlands was hidden by human-made wetland gain with an offset of 15.6 × 103 km2. About 14.0 × 103 km2 expansion of surface water extent also hides the loss of vegetated wetlands.

“This study provides important data information. The ‘zero net loss target’ is not appropriate for sustainable wetland conservation,” Zongming Wang says.

“Sustainable management and effective conservation of wetlands require a focus not only on wetland areas but also on the landscape structure and the small patches and areas of wetlands that deliver important ecosystem services. Enhanced protection accompanied by increased ecological projects and improved management systems as well as future changes in response to diverse climate change must be assessed. Unreasonable internal conversions among wetland types and the invasion of alien species should be controlled,” Prof. Ming Jiang (Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) added.

“China_Wetlands will be a critical wetland dataset for ecological research and assessment of national and global environmental objectives,” Wenping Yuan (Peking University) says.

“We are pleased to share this important wetland product. In fact, many scholars have already applied to use the product,” Dehua Mao concludes.

Journal Reference:

Dehua Mao, Ming Wang, Yeqiao Wang, Ming Jiang, Wenping Yuan, Ling Luo, Kaidong Feng, Duanrui Wang, Hengxing Xiang, Yongxing Ren, Jianing Zhen, Mingming Jia, Chunying Ren, Zongming Wang, ‘The trajectory of wetland change in China between 1980 and 2020: hidden losses and restoration effects’, Science Bulletin 70, 4, 587-596 (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.scib.2024.12.016

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Science China Press

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay