Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press daily roundup, featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

Oxygen for Mars

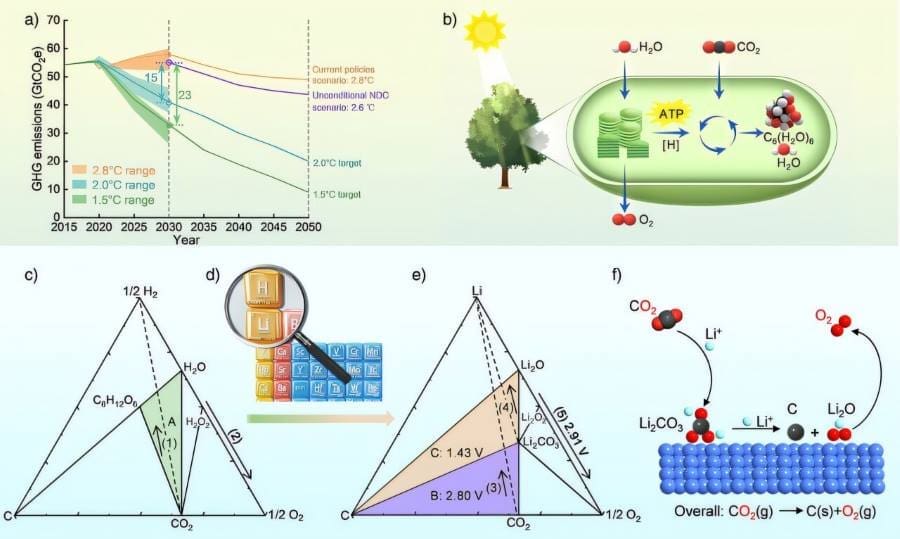

To mitigate global climate change, emissions of the primary culprit, carbon dioxide, must be drastically reduced. A newly developed process helps solve this problem: CO2 is directly split electrochemically into carbon and oxygen. As a Chinese research team reports in the journal Angewandte Chemie, oxygen could also be produced in this way under water or in space — without requiring stringent conditions such as pressure and temperature.

Leafy plants are masters of the art of carbon neutrality: during photosynthesis, they convert CO2 into oxygen and glucose. Hydrogen atoms play an important role as “mediators”. However, the process is not particularly efficient. In addition, the oxygen produced does not come from the CO2 but from the absorbed water. True splitting of CO2 is not taking place in plants and also could not be achieved at moderate temperatures by technical means so far.

Ping He, Haoshen Zhou, and their team at Nanjing University, in collaboration with researcher from Fudan University (Shanghai) have now achieved their goal to directly split CO2 into elemental carbon and oxygen. Instead of hydrogen, the “mediator” in their method is lithium. The team developed an electrochemical device consisting of a gas cathode with a nanoscale cocatalyst made of ruthenium and cobalt (RuCo) as well as a metallic lithium anode.

CO2 is fed into the cathode and undergoes a two-step electrochemical reduction with lithium. Initially, lithium carbonate Li2CO3 is formed, which reacts further to produce lithium oxide Li2O and elemental carbon. In an electrocatalytic oxidation process, the Li2O is then converted to lithium ions and oxygen gas O2. Use of an optimized RuCo catalyst allows for a very high yield of O2, over 98.6 %, significantly exceeding the efficiency of natural photosynthesis.

As well as pure CO2, successful tests were also carried out with mixed gases containing varying fractions of CO2, including simulated flue gas, a CO2/O2 mixture, and simulated Mars gas. The atmosphere on Mars consists primarily of CO2, though the pressure is less than 1 % of the pressure of Earth’s atmosphere. The simulated Mars atmosphere thus contained a mixture of argon and 1 % CO2.

If the required power comes from renewable energy, this method paves the way toward carbon neutrality. At the same time, it is a practical, controllable method for the production of O2 from CO2 with broad application potential — from the exploration of Mars and oxygen supply for spacesuits to underwater life support, breathing masks, indoor air purification, and industrial waste treatment.

***

Dr. Ping He is a Professor and Head of the Department of Energy Science and Engineering at the College of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Nanjing University. His research interests focus on transformative electrochemical energy technologies, including high-energy-density batteries, electrochemical CO2 reduction, and lithium resource extraction and recycling. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry and serves as an Associate Editor for ACS Energy & Fuels.

Journal Reference:

Li, W., Mu, X., Yang, S., Wang, D., Wang, Y., Zhou, H. and He, P., ‘Artificial Carbon Neutrality Through Aprotic CO2 Splitting’, Angewandte Chemie International Edition e202422888 (2025). DOI: 10.1002/anie.202422888

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Wiley

5,700-year storm archive shows rise in tropical storms and hurricanes in the Caribbean

In the shallow waters of the Lighthouse Reef Atoll, located 80 kilometers off the coast of the small Central American country of Belize, the seabed suddenly drops steeply. Resembling a dark blue eye surrounded by coral reefs, the “Great Blue Hole” is a 125-meter-deep underwater cave with a diameter of 300 meters, which originated thousands of years ago from a karst cave located on a limestone island.

During the last ice age, the cave’s roof collapsed. As ice sheets melted and global sea level started to rise, the cave was subsequently flooded.

In the summer of 2022, a team of scientists – led by Prof. Eberhard Gischler, head of the Biosedimentology Research Group at Goethe University Frankfurt, and funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) – transported a drilling platform over the open sea to the “Great Blue Hole”.

They then proceeded to extract a 30-meter sediment core from the underwater cave, which has been accumulating sediment for approximately 20,000 years. The core was subsequently analyzed by a research team from the universities of Frankfurt, Cologne, Göttingen, Hamburg, and Bern.

The results were published in the journal Science Advances.

Coarse layers are a testimony to tropical storms

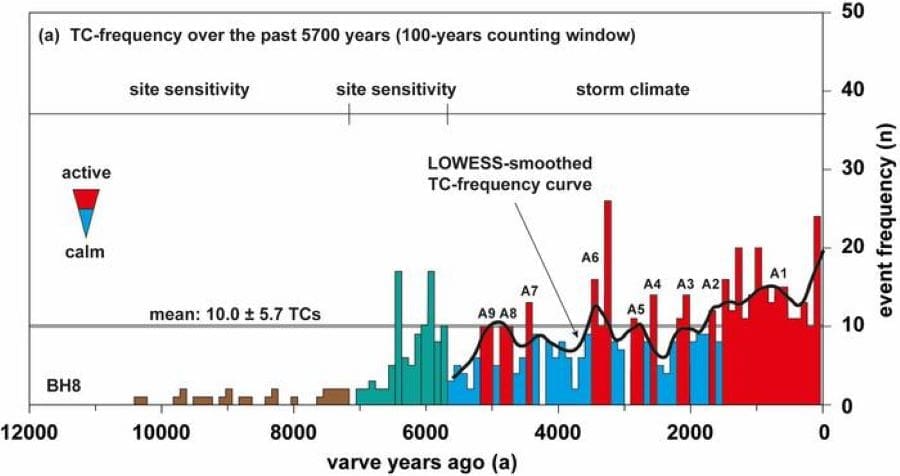

Some 7,200 years ago, the former limestone island of what is now Lighthouse Reef was inundated by the sea. The layered sediments at the bottom of the “Great Blue Hole” serve as archive for extreme weather events of the past 5,700 years, including tropical storms and hurricanes.

Dr. Dominik Schmitt, a researcher in the Biosedimentology Research Group and the study’s lead author, explains: “Due to the unique environmental conditions – including oxygen-free bottom water and several stratified water layers – fine marine sediments could settle largely undisturbed in the ‘Great Blue Hole.’ Inside the sediment core, they look a bit like tree rings, with the annual layers alternating in color between gray-green and light green depending on organic content.”

Storm waves and storm surges transported coarse particles from the atoll’s eastern reef edge into the “Great Blue Hole”, forming distinct sedimentary event layers (tempestites) at the bottom. “The tempestites stand out from the fair-weather gray-green sediments in terms of grain size, composition, and color, which ranges from beige to white,” says Schmitt.

The research team identified and precisely dated a total of 574 storm events over the past 5,700 years, offering unprecedented insights into climate fluctuations and hurricane cycles in the southwestern Caribbean. Instrumental data and human records available to date had only covered the past 175 years.

Rising incidence of storms in the southwestern Caribbean

The distribution of storm event layers in the sediment core reveals that the frequency of tropical storms and hurricanes in the southwestern Caribbean has steadily increased over the past six millennia.

Schmitt explains: “A key factor has been the southward shift of the equatorial low-pressure zone. Known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone, this zone influences the location of major storm formation areas in the Atlantic and determines how tropical storms and hurricanes move and where they make landfall in the Caribbean.”

The research team was also able to correlate higher sea-surface temperatures with increased storm activity. Schmitt states: “These shorter-term fluctuations align with five distinct warm and cold climate periods, which also impacted water temperatures in the tropical Atlantic.”

Climate change results in greater storm activity

Over the past six millennia, between four and sixteen tropical storms and hurricanes passed over the “Great Blue Hole” per century. However, the nine storm layers from the past 20 years indicate that extreme weather events will be significantly more frequent in this region in the 21st century.

Gischler warns: “Our results suggest that some 45 tropical storms and hurricanes could pass over this region in our century alone. This would far exceed the natural variability of the past millennia.”

Natural climate fluctuations cannot account for this increase, the researchers emphasize, pointing instead to the ongoing warming during the Industrial Age, which results in rising ocean temperatures and stronger global La Niña events, thereby creating optimal conditions for frequent storm formation and their rapid intensification.

Journal Reference:

Dominik Schmitt, Eberhard Gischler, Martin Melles, Volker Wennrich, Hermann Behling, Lyudmila Shumilovskikh, Flavio S. Anselmetti, Hendrik Vogel, Jörn Peckmann, Daniel Birgel, ‘An annually resolved 5700-year storm archive reveals drivers of Caribbean cyclone frequency’, Science Advances 11, 11, eads5624 (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ads5624

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Goethe University Frankfurt

Wildfires, windstorms and heatwaves: How extreme weather threatens nature’s essential services

How much will strawberry harvests shrink when extreme heat harms pollinators? How much will timber production decline when windstorms flatten forests? How much will recreational value disappear when large wildfires sweep through Colorado’s mountain towns?

These are some critical questions that a new computer simulation, co-developed by a CU Boulder ecologist, can answer. In a paper published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, researchers presented a model that aims to understand how extreme weather events, worsened by climate change, will affect ecosystems and the benefits they provide to humans.

Based on the model, a Minnesota forest could lose up to 50% of its timber revenue if a severe windstorm hits.

“With climate change, there’s an urgent need to incorporate the impacts of extreme events like mega-fires and hurricanes have on the benefits nature provides,” said Laura Dee, the paper’s first author and associate professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. “This research is an important step toward anticipating impacts to ecosystem services so that we can adapt management strategies accordingly.”

Scientists use the term “ecosystem services” or “nature’s contributions to people” to refer to the essential functions that nature provides to support human life and well-being. Tree roots purify water, insects pollinate crops and forests lock away carbon, helping to stabilize the climate. In addition to these tangible benefits, mountains, lakes and oceans offer recreational enjoyment for people and hold cultural significance for communities.

Previous models for predicting how ecosystems respond to climate change tend to assume that changes are steady. For example, a gradual increase in global temperatures of up to 1.5°C. But as climate change makes extreme weather events like wildfires and floods more frequent and severe, the impacts from rapid disturbances have become significant.

Dee and her team developed a new mathematical model that tracks how the probability of an extreme weather event affects certain species and the ecosystem services they provide. The model also incorporates how people value these services.

To show the model’s potential, the team applied it to calculate the possible consequences of extreme windstorms in a mid-latitude forest in northern Minnesota. The model considered how winds have different effects on different tree species, each of which has distinct economic value. For example, thick white cedar trees are more resilient to windstorms than balsam fir trees, but the balsam fir can sell at a higher price.

The model suggested that a windstorm, depending on its intensity, can slash the total timber value of the forest by 23% to 50%. Recreational opportunities like hiking and camping would also take a hit.

Dee said that researchers and land management officials could use the model to evaluate the impacts of any disturbances, from drought to invasive species.

Dee’s research group at CU Boulder studies how prescribed fire strategies, or deliberately burning specific areas under controlled conditions, can reduce wildfire risks in Colorado.

The new model also helps to identify the areas where scientists should prioritize burning to achieve the greatest reduction in fire risk, while also considering other benefits trees provide, such as removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and filtering water.

“Nature’s contributions to people have not typically been valued and are usually left out of key decision-making processes when developing land management policies and strategies,” Dee said.

The United Nation’s World Meteorological Organization announced that more than 150 unprecedented extreme weather events struck Earth last year. With disturbances becoming more common, future Gross Domestic Product analyses, for example, should start incorporating the impacts of climate change, Dee added.

“If we fail to consider the growing risks from extreme weather events, we could lose more than we realize,” she said.

Journal Reference:

Dee, L.E., Miller, S.J., Helmstedt, K.J. et al., ‘Quantifying disturbance effects on ecosystem services in a changing climate’, Nature Ecology & Evolution 9, 436–447 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-024-02626-y

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Yvaine Ye | University of Colorado at Boulder

Tree diversity helps reduce heat peaks in forests

A forest with high tree-species diversity is better at buffering heat peaks in summer and cold peaks in winter than a forest with fewer tree species. This is the result of a study led by researchers from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), Leipzig University, and the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU).

The study was carried out in a large-scale planted forest experiment in China, and has been published in the journal Ecology Letters. It provides yet another argument for diversifying tree species in forests, especially under ongoing climate change.

Temperatures are increasing at many locations worldwide, largely due to increasing greenhouse gases. These climatic shifts include changes in temperature extremes: While cold peaks in winter are already decreasing in number (i.e., they are becoming warmer), heat peaks are increasing. Trees have long been known to buffer temperature extremes, reducing heat peaks within forests during hot summer and reducing cold peaks during wintertime. However, it was unknown whether the number of tree species, “tree species richness”, could increase the potential of forests to buffer heat and cold peaks.

“Former research has shown that the buffered temperatures below the tree canopy are important for forest biodiversity as they slow down the climate change-driven shift towards species that prefer warm temperatures,” says co-first author Dr Florian Schnabel from the University of Freiburg, who oversaw this research while working at iDiv and Leipzig University and continued this work in Freiburg. “At the same time, the effect of tree diversity, a key facet of forest biodiversity, on forest temperature buffering remains largely unknown.”

Largest planted tree diversity experiment worldwide

To answer this question, the researchers took advantage of the largest planted tree diversity experiment worldwide, located in subtropical China. In the so-called BEF-China experiment, several hundred thousand trees were planted into plots consisting of 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, or 24 different tree species, respectively. Since the establishment of iDiv, the BEF-China project has been one of iDiv’s key research platforms, resulting in a joint Sino-German international research training group that conducted the forest temperature measurements in this study over six years (2015-2020).

Tree species diversity buffers temperature peaks

The results showed that forests rich in tree species lowered temperatures below the canopy during heat peaks more than forests with fewer tree species. The effect was strongest during midday heat in summer. Cooling was up to 4.4°C stronger in experimental plots with 24 species compared to plots with just a single species.

Species-rich forests were also better at increasing temperatures during cold hours at nighttime and during winter. However, when looking at monthly averages, the researchers found no difference between species-poor and species-rich forests.

Canopy density and structural diversity explain diversity effect

The researchers also found a likely explanation for how species richness may affect temperature buffering. Experimental plots with many tree species showed both a higher canopy density (more leaf area per ground area) and a higher structural diversity (for instance, a higher variety of smaller and larger trees). These factors enhanced temperature buffering, probably by reducing the mixing of air masses.

“Temperature buffering effects are nice for humans seeking relief during a heat wave, but they also affect the ecosystem itself,” says co-first author Dr Rémy Beugnon from iDiv, Leipzig University, and the Centre d’Ecologie Fonctionnelle et Evolutive. “A buffered microclimate creates more favorable conditions for ecosystems and protects the services they offer. Under a buffered climate, forests are likely to grow and regenerate more effectively, while soils function better, supporting greater biodiversity, improving nutrient cycles, and increasing carbon storage.”

Good reasons for promoting species richness

The new study adds evidence to a list of arguments why increasing tree species richness may benefit people and nature. “Although typical tree monocultures as they are planted globally are important for providing timber, they do not only harbour less biodiversity than natural or diverse planted forests but provide fewer other services than wood production,” says senior author Prof Helge Bruelheide from iDiv and MLU. “Our study clearly showed that this temperature buffering effect of tree species richness has the potential to mitigate negative effects of global warming and climate extremes on the whole forest ecosystem.”

The authors conclude: “Overall, our findings thus highlight the benefits of diverse planted forests for large-scale forest restoration initiatives and urban forests that aim at reducing thermal stress in a warming world.”

Journal Reference:

Schnabel, F., Beugnon, R., Yang, B., Richter, R., Eisenhauer, N., Huang, Y., Liu, X., Wirth, C., Cesarz, S., Fichtner, A., Perles-Garcia, M.D., Hähn, G.J.A., Härdtle, W., Kunz, M., Castro Izaguirre, N.C., Niklaus, P.A., von Oheimb, G., Schmid, B., Trogisch, S., Wendisch, M., Ma, K. and Bruelheide, H., ‘Tree Diversity Increases Forest Temperature Buffering via Enhancing Canopy Density and Structural Diversity’, Ecology Letters 28, 3, e70096 (2025). DOI: 10.1111/ele.70096

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay