Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press daily roundup, featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

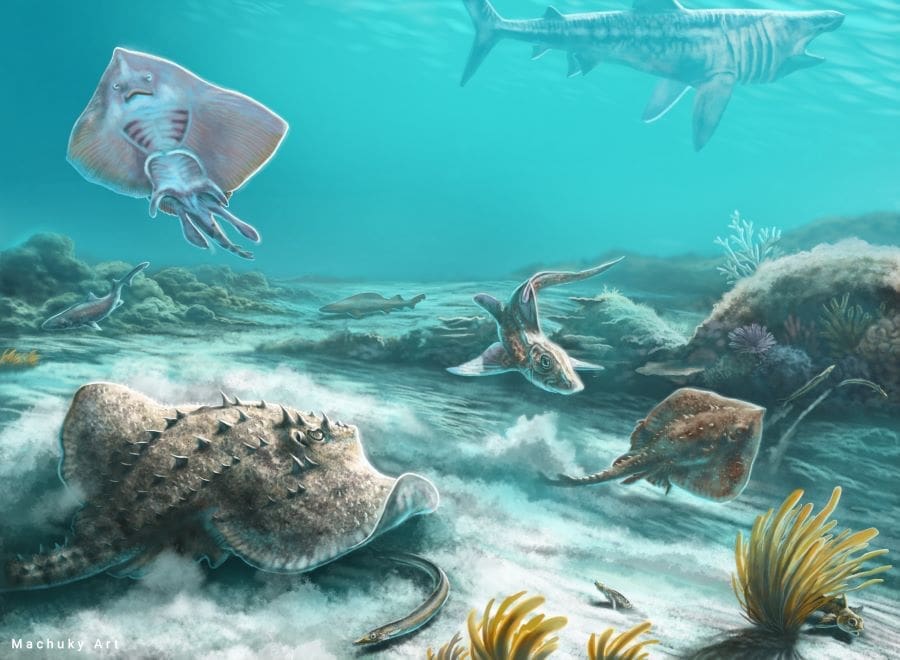

Thorny skates come in snack and party sizes. After a century of guessing, scientists now know why

When Jeff Kneebone was a college student in 2002, his research involved a marine mystery that has stumped curious scientists for the last two decades. That mystery had to do with thorny skates (Amblyraja radiata) in the North Atlantic. In some parts of their range, individuals of this species come in two distinct sizes, irrespective of sex, and no one could figure out why. At the time, neither could Kneebone.

In a new study, published in Nature Communications, Kneebone and researchers from the Florida Museum of Natural History say they’ve finally found an answer. And it’s all thanks to COVID-19.

People have known about the size discrepancy in thorny skates for nearly a century, but it became critically important beginning in the 1970s, when their numbers took a nosedive. The cause of the decline was thought to be overfishing by humans, and the solution was simple. In 2003, a strict fishing moratorium in the United States was put in place for thorny skates and another species, the barndoor skate, that was also doing poorly.

“The barndoor skate rebounded to the point where they’re now allowed to be harvested again, but for whatever reason, the thorny skate has remained low, despite 20 years of protection,” said Kneebone, who currently works as a senior scientist at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium.

According to survey data collected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, thorny skates have declined by 80% to 95% in some areas, particularly the Gulf of Maine, and they’re also languishing in low numbers in Canadian waters off the Scotian Shelf.

Thorny skates have a large distribution. They can be found from South Carolina up to the Arctic Circle and east through Scotland, Norway and Russia. In the Arctic and European part of their range, thorny skates come in just one size. It’s only along the coast of North America that small and large varieties coexist.

“No one could understand what the deal was with these skates,” said study co-author Gavin Naylor, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research at the Florida Museum of Natural History. Scientists had tried studying thorny skate DNA to see if there were any differences between the large and small sizes, but they came up empty-handed. “The big forms are twice the size, and it takes them 11 years to reach adulthood. The small forms are mature by the time they’re six years old. There’s got to be genetic differences.”

Naylor thought he might be able to crack the code.

The idea was simple. Previous studies had tried to answer the question by analyzing a few short DNA sequences taken from a small number of thorny skates. It was a good strategy, Naylor reasoned, but fell short because researchers hadn’t yet processed nearly enough DNA.

Instead, what was needed was a gene capture approach: a labor-intensive method that allows researchers to collect DNA sequence data from thousands of sequences throughout an organism’s genome, the term used to describe DNA stored in the nuclei of cells. Most importantly, they’d do this for hundreds of thorny skates, which would provide them ample data to scour.

He put the word out to the scientific community, and people sent the team more than 600 tissue samples collected across much of the Northern Hemisphere, and he made the costly preparations to get the lab work underway, with funding from the Lenfest Foundation and the National Science Foundation.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and the subsequent restrictions that were put in place made it impossible to conduct extensive, in-person lab work, putting the project on indefinite hiatus.

One of Naylor’s postdoctoral researchers at the time, Shannon Corrigan, pulled together a salvage mission. If they couldn’t collect gene capture DNA from hundreds of thorny skates, they could sequence the entire genome of four or five individuals. This would drastically cut down on the amount of in-person work that needed to be done.

It was a risky plan. There was only a small chance they would find what they were looking for by sequencing genomes, and they only had enough funding to do one or the other.

It was a Hail Mary, Naylor said, but one that paid off. Had they used the original gene capture idea, “we would have missed it entirely.”

As it was, they only nearly missed it. The study’s first author, Pierre Lesturgie, was tasked with analyzing the genome — all 2.5 billion base pairs of it — once it had been sequenced. As he was combing through the data, something strange caught his eye.

“There was a large region on chromosome two that we thought was weird. Since it was behaving in a way we didn’t understand, we considered removing it from the analysis,” Lesturgie said. He thought it might be an aberration or potentially an error introduced during the sequencing process, and worried it would reduce the accuracy of their results. He was about to trash it when Naylor mentioned it looked like the sort of thing you’d get from a gene inversion, a natural process in which a sequence of DNA is flipped in the wrong direction.

Most organisms, including humans, have at least a few inversions in their genomes, so they’re not uncommon, but they seldom result in observable differences between individuals. But because it was all the researchers had to go on, they checked to see if the inverted sequence was present in both large and small thorny skates. It wasn’t. Only large thorny skates had the mirrored stretch of DNA. They’d need to do more work to confirm it, but they’d found their answer. Cue the popping bottles of champagne and celebratory good cheer.

Figuring out what caused the size difference is only the first step, Kneebone said. Now researchers can make headway on developing a conservation plan. The next step will involve good old-fashioned observation. Before the discovery of the gene inversion, it was difficult — and in some cases impossible — to distinguish between the large and small types.

“We could identify the large males and females, because they’re bigger than anything else,” Naylor said. At maturity, both large and small males develop long, trailing claspers on either side of their tale, giving them the overall appearance of a kite with streamers. “So when you’ve got a small male with large claspers, we know it’s an adult. But we can’t do anything with the small females, because we don’t know whether they’re just babies on their way to getting big.”

This limitation has hampered research on the species, Kneebone said. “The big question has always been, what do the life histories of the two morphs look like? Currently, they’re not discriminated in the stock assessment, so a thorny skate is a thorny skate is a thorny skate.”

The final step will be figuring out why thorny skates are continuing to decline in parts of their range. Fortunately, scientists already have a few good leads. Current evidence suggests it’s harder for the two sizes to interbreed in places where they’re declining than it is in others. It’s possible this natural and partial barrier to reproduction cold be exacerbated by climate change.

Thorny skates are having the most trouble in the Gulf of Maine, where sea surface temperatures have increased faster than 99% of the world’s oceans over the last several years. This has had all sorts of unpleasant effects, like the collapse of cod fisheries in the region.

Whether climate change is partially responsible for the plight of the thorny skate and, if so, why it has an undue negative influence on this single species compared with other skates that live in the same area, remains to be seen. To determine that, Kneebone said they’ll need more data.

“We’re trying to use the best available science to make decisions about how to best manage and sustain populations.”

Journal Reference:

Lesturgie, P., Denton, J.S.S., Yang, L. et al., ‘Short-term evolutionary implications of an introgressed size-determining supergene in a vulnerable population’, Nature Communications 16, 1096 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-56126-z

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Jerald Pinson | Florida Museum of Natural History

Kansas, Missouri farmers avoid discussing climate change regardless of opinions, study finds

We have all avoided having conversations if the topic is controversial or may lead to an argument. Farmers, who are on the front lines of climate change, avoid talking about it with their neighbors, community members, elected officials and even their own families because of potential conflict and harm to their livelihood, new research from the University of Kansas has found.

Researchers conducted interviews with more than 20 farmers in Kansas and Missouri to understand their communication about climate change. Results showed respondents had a range of views on climate change from being convinced of its effects and taking action in their farming operations to skepticism — but all avoided discussing it to varying extents.

“People were worried about a variety of reactions. Some said they couldn’t even talk about it with their families because they would give them a weird look if they brought it up,” said Hong Tien Vu, associate professor of journalism & mass communications at KU and lead author of the study. “That was a low-level worry, but others said they had heard people laughing at them or were concerned about their neighbors not working with them if they had different opinions.”

The study was born from research Vu and students started during the COVID-19 pandemic. The group received private donor funding to study local climate change effects. Students interviewed scientists on campus and farmers in surrounding communities about climate change, their views on it and how it affects them. Farmers were reluctant to discuss the topic on camera.

“When we talk about climate change, we tend to look at broad effects like sea level rise. It can be difficult for people to find relevance in topics like that in their lives. We wanted to focus on factors that relate to people’s lives here in Kansas,” Vu said. “We wanted to interview farmers specifically because they are on the front lines of climate change impacts, both in terms of contributing to it through factors like emissions and feeling the effects of it.”

Given farmers’ reluctance to discuss the topic on camera, researchers decided to conduct interviews in which they could guarantee anonymity for respondents. Farmers then discussed their opinions on the topic, how it affects their lives and work, and why they avoid discussing it.

The researchers examined the topic through the lens of spiral of silence theory, which posits that when discussing controversial topics, people judge the prevailing opinion of others before deciding whether to speak. If they feel they are in the minority, people will often choose not to discuss a topic, which can have long-term ramifications, including silencing people and exacerbating problems that people choose not to address.

The results confirmed the prevalence of a spiral of silence among Kansas and Missouri farmers. The respondents were both men and women, ranging in age from their 20s to 70s. When asked their thoughts on climate change, responses ranged from believing it is real, scientifically proven and having effects now, to being skeptical both of its prevalence and whether it is caused by humans. But across the board, respondents indicated they generally avoid discussing the topic.

The farmers gave a range of reasons why they avoid it. Many simply did not want a conflict that could result in violence or an argument with neighbors or community members. Some feared it could damage their business, as neighbors might be less likely to work with them and share equipment or people might give them a negative online review and tell people not to buy their products at farmers’ markets and other locales if they disagreed with their views.

Farmers said they also tried to gauge a person’s opinions based on interpersonal cues before deciding whether to discuss climate change. For example, the type of vehicle a person drives, whether a large pickup or hybrid car, can provide clues about their opinions on the matter.

Spiral of silence theory holds that people traditionally used news media to gauge political opinion on a potentially controversial topic. However, respondents in the study indicated they felt news media only politicized the topic and therefore was not a trustworthy way of determining how people felt. Instead, many turned to social media where they could see if people posted on the topic or to find others to discuss it with, without fear of arguments or contentious conversations.

“The algorithm can allow you to choose who to talk to or who to exclude,” Vu said of social media. “People also often feel masked on social media. To me, that is a way of losing conversations and can give you a false sense of prevalence of opinions by eliminating cross examples.”

The study, co-written with Nhung Nguyen, lecturer; Nazra Izhar, doctoral candidate; and Vaibhav Diwanji, assistant professor of journalism and mass communications, all at KU, was published in the journal Environmental Communication.

When asked how they deal with the effects of climate change, several farmers reported taking measures such as switching to organic methods, fallowing fields to counter overuse of land and seeking information on more sustainable practices. Several also reported feeling isolated in general and given that they felt they could not discuss climate change, took to journaling as a way to process their thoughts.

Vu and colleagues, who have studied how climate change is viewed and reported globally, said understanding how the issue is viewed and discussed in more local settings is also important because people need to work together in day-to-day operations like farming as well as for policy solutions. If pressing issues are not discussed, it can negatively affect how they are dealt with on interpersonal levels and at local levels of government, they argue.

As part of the larger research project, the group plans to use journalistic storytelling techniques to document how people are dealing with climate change locally and their opinions on the topic. They also plan to test the effects of different content elements such as psychological distance and modalities like text, video, podcast or virtual reality on public perceptions of and behaviors toward sustainability.

“In our conversations with farmers, we found they often felt excluded from other conversations on climate change,” Vu said. “It felt like they were picking their battles with everyone, because they are often blamed for things like emissions, while working on adjusting their farming practices for mitigation and adaptation purpose. We think not talking about climate change is a serious issue.”

Journal Reference:

Vu, H. T., Nguyen, N., Izhar, N., & Diwanji, V., ‘“Climate Change is Real, but I Don’t Wanna Talk About It”: Unraveling Spiral of Silence Effects Regarding Climate Change Among Midwestern American Farmers’, Environmental Communication 1–16 (2025). DOI: 10.1080/17524032.2025.2477260

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Mike Krings | University of Kansas

Red coral colonies survive a decade after being transplanted in the Medes Islands

The red coral colonies that were transplanted a decade ago on the seabed of the Medes Islands have survived successfully. They are very similar to the original communities and have contributed to the recovery of the functioning of the coral reef, a habitat where species usually grow very slowly.

Thus, these colonies, seized years ago from illegal fishing, have found a second chance to survive, thanks to the restoration actions of the University of Barcelona teams, in collaboration with the Institute of Marine Sciences (ICM – CSIC), to transplant seized corals and mitigate the impact of poaching.

These results are now presented in an article in the journal Science Advances. Its main authors are the experts Cristina Linares and Yanis Zentner, from the UB’s Faculty of Biology and the Biodiversity Research Institute (IRBio), and Joaquim Garrabou, from the ICM (of the Spanish National Research Centre, CSIC).

The findings indicate that actions to replant corals seized by the rural corps from poachers are effective not only in the short term — the first results were published after four years — but also in the long term, i.e. ten years after they have been initiated. Under the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030) and the European Union’s Nature Restoration Act, the paper stands out as one of the few research studies that has evaluated the success of long-term restoration in the marine ecosystem.

Transplanted colonies surviving and helping to structure the coralligenous habitat

Red coral (Corallim rubrum) poaching has been a threat even in marine protected areas and, in addition, due to the slow growth of this species, populations are still far from pristine conditions.

The team’s restoration work was carried out in the Montgrí, Medes Islands and Baix Ter Natural Park, “at a depth of around 18 metres, in a little-visited area where no poaching has been observed in recent years and which, for the moment, does not seem to be affected by climate change,” explains Cristina Linares, professor at the UB’s Department of Evolutionary Biology, Ecology and Environmental Sciences.

The results of this research study, which has received funding from both the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities and the European Union’s Next Generation funds, reveal the high survival of the transplanted red coral colonies after so many years.

“The restored community — i.e. the set of organisms in the environment where the transplanted coral is found — has been completely transformed in just ten years,” says Linares. “The community has also assimilated the structure expected in natural red coral communities. This reinforces the key value of habitat-generating species such as red coral, and the benefits that can grow from targeting them for conservation and restoration actions,” he continues.

Preventing the impact of climate change on transplanted coral

Rising temperatures and heatwaves caused by global change are causing mortality in populations of red coral and 50 other species in the Mediterranean. In addition, the long tradition of coral fishing for the jewellery world also threatens its colonies, which have reduced presence and a decisive ecological role in areas of difficult access and high depths.

“If there is no additional impact — such as climate change —, we expect to reach a well-developed community on a much faster timescale than we originally expected,” says Yanis Zentner (UB – IRBio), predoctoral researcher and first author of the paper.

“It is a biological community with a very slow dynamic, so being able to transplant coral colonies of a certain size means ‘gaining’ a lot of time in ecological restoration. However, while the rapid transformation observed in this study is encouraging, whether this system is capable of fully restoring the functionality of a pristine coral reef remains to be seen,” warns Zentner.

Regarding red coral, it only makes sense to apply this methodology in coralligenous habitats or in caves, which is the natural habitat of the species. “In addition, it is advisable to avoid the potential impact of climate change and to carry out these actions from a depth of 30 metres, where the effect of global change is less,” says the expert.

Assessing restoration with long-term timescales

Traditionally, the success of this marine restoration actions profile of is evaluated based on the short-term survival of the transplanted organisms. “This approach is limited, especially for long-lived species such as coral, which could reach a longevity of 50 to 100 years. Many target species need more time to recover than the monitoring period, which mostly focuses on the first few years after restoration. Similarly, it also does not allow for the assessment of ecosystem-scale changes, such as the recovery of functions and services,” say Linares and Zentner.

The new study is a first step towards working at relevant temporal and ecological scales, carrying out long-term monitoring through community-scale analyses, which allow inferring changes in the functions and services provided by the species present. “More specifically, dominance and functional diversity are indicators that allow us to quantify changes in the functional structure of the coralligenous habitat: in this case, we have been able to detect an increase in the structural complexity and resilience of the restored community,” note the experts.

Tropical systems are the marine habitats where most coral restoration has been carried out, but its long-term success has often not been assessed, which is important given the increasing impact of climate change. In the Mediterranean, the research team has been involved in previous studies on the restoration of corals and gorgonians rescued from fishing nets and transplanted to protected deep sea beds.

Globally, restoration actions in the marine environment are still at an early stage. In particular, the first scientific methodologies are only just being tested, and most are aimed more at mitigating an impact than at restoring an entire ecosystem. At the same time, there is still a significant lack of best practice protocols for these actions.

“For restoration to be efficient, the source of stress that has degraded the system to be restored must be removed. In the case of the marine environment, due to global change, there is practically no corner of the world that is protected from human impacts. Therefore, before restoring, we must consider how to protect the sea effectively,” note the researchers.

“On the other hand, we must manage to increase the scale at which we work, since, due to the impediments of working in the marine environment, many restoration actions (including this study) are carried out on a small local scale, and have a low return at the ecosystem scale.”

Journal Reference:

Zentner, Yanis; Garrabou, Joaquim; Margarit, Núria; Rovira, Graciel·la; Gómez-Gras, Daniel; Linares, Cristina, ‘Active restoration of a long-lived octocoral drives rapid functional recovery in a temperate reef’, Science Advances 11, eado5249 (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ado5249

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Barcelona

Stormy rains in the Sahara offer clues to past and future climate changes

New research reveals that heavy precipitation sourced from the Atlantic Ocean, are the primary drivers of present-day lake filling in the northwestern Sahara. The study finds that only the most intense and prolonged precipitation events trigger lake-filling episodes, challenging long-standing assumptions about past climate conditions in the region. These findings suggest that projections of enhanced rainfall intensity and frequency in the Sahara could potentially reshape water availability in the desert.

A new study supervised by Dr. Moshe Armon from the Institute of Earth Sciences at Hebrew University and Dr. Franziska Aemisegger from University of Bern, in collaboration with Dr. Elad Dente from University of Haifa, led by their student Joëlle Rieder at ETH Zurich, recently published in Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, provides new insights into the meteorological processes responsible for the filling of a normally dry lake in the northwestern Sahara.

The research offers a fresh perspective on past climate variations and suggests we can learn from past flooding of the lake on ongoing climate change and future water resources in the desert.

The Sahara Desert, one of the driest places on Earth, has not always been as arid as it is today. Prehistoric evidence of wetlands in the Sahara points to wetter periods in the past, but scientists have long debated the sources of moisture responsible for these ancient water bodies. The study examines how the currently dry Sebkha El-Melah lake in western Algeria is occasionally filled with water, shedding light on the extreme storm events required to sustain such bodies of water.

Key Findings:

- Between 2000 and 2021, hundreds of powerful rainstorms were recorded in the lake’s drainage basin, yet only six instances led to substantial lake-filling events.

- These lake-filling events were driven by precipitation systems originating from the Atlantic Ocean, rather than equatorial sources as previously believed.

- The moisture transport process involves the interaction of extratropical cyclones near the North African Atlantic coast with upper-level atmospheric patterns, creating conditions favorable for heavy precipitation events.

- A crucial factor in these events is the recycling-domino effect, in which moisture is progressively transported and enhanced over the Sahara before reaching the lake’s drainage basin.

- The stationarity of weather systems, lasting typically three days, contributes significantly to the occurrence of lake-filling events.

This research challenges conventional theories suggesting that prehistoric lakes in the Sahara were primarily filled by monsoonal rains from the south. Instead, it highlights the role of Atlantic-origin storms, which deliver oceanic moisture into the desert, bypassing the Atlas Mountains. These findings have important implications for understanding past climate conditions and predicting future hydrological changes in desert environments.

The study further suggests that potential future climate shifts — driven by global warming — have the potential to fill Saharan lakes not only due to increased rainfall, but also because of changes in the frequency of extreme rainstorms. This could reshape water availability in the region, with significant consequences for ecosystems and human settlements.

By integrating climate science, meteorology, remote sensing, and hydrology, this research bridges a critical knowledge gap and provides a framework for future studies on Sahara Desert hydrology and climate dynamics.

Journal Reference:

Rieder, J. C., Aemisegger, F., Dente, E., and Armon, M., ‘Meteorological ingredients of heavy precipitation and subsequent lake-filling episodes in the northwestern Sahara’, Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 29, 1395–1427 (2025). DOI: 10.5194/hess-29-1395-2025

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay