Summary:

As global temperatures rise, drier air could pose a growing risk to respiratory health by dehydrating human airways, increasing inflammation, and potentially worsening conditions such as asthma and chronic cough. Researchers explain that as the planet warms, vapor pressure deficit (VPD) — a measure of how much moisture the air can absorb — rises sharply. This leads to higher evaporation rates, drying out not only ecosystems but also human mucosa.

The findings were published in Communications Earth & Environment. Laboratory experiments on human airway cells showed that exposure to dry air resulted in thinner mucus and increased inflammatory markers. Similar effects were observed in animal models, where mice with preexisting airway dryness exhibited heightened immune responses after dry air exposure.

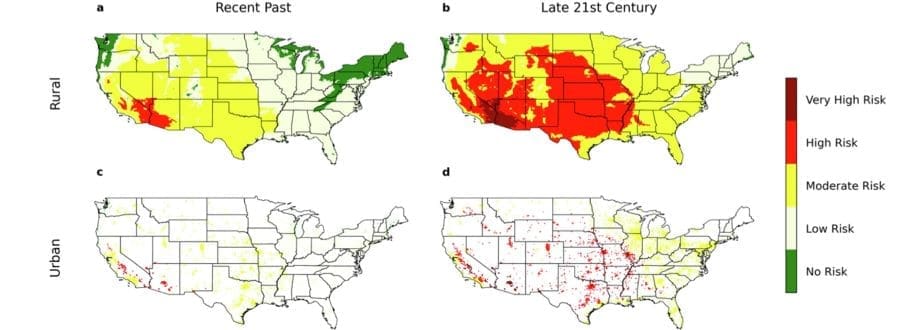

Researchers warn that, based on climate models, much of the U.S. could face elevated risks of airway inflammation by the latter half of the century due to drier air. They emphasize that maintaining airway hydration is as crucial as protecting air quality, with potential implications for other conditions such as dry eye.

Global warming can lead to inflammation in human airways, new research shows

In a recent, cross-institutional study partially funded by the National Institutes of Health, researchers report that healthy human airways are at higher risk for dehydration and inflammation when exposed to dry air, an occurrence expected to increase due to global warming. Inflammation in human airways is associated with such conditions as asthma, allergic rhinitis and chronic cough.

Researchers say that as the Earth’s atmosphere heats up, with relative humidity staying mostly the same, a property of the atmosphere called vapor pressure deficit (VPD) increases at a rapid rate. VPD is a measure of how “thirsty” for water air can be. The higher VPD becomes, the greater the evaporation rate of water, thus dehydrating planetary ecosystems.

Based on mathematical predications and experiments, researchers now explain that higher VPD can dehydrate upper airways and trigger the body’s inflammatory and immune response. In the full report, they also say that such dehydration and inflammation can be exacerbated by mouth breathing (rates of which are also increasing) and more exposure to air-conditioned and heated indoor air.

“Air dryness is as critical to air quality as air dirtiness, and managing the hydration of our airways is as essential as managing their cleanliness,” says lead author David Edwards, adjunct professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “Our findings suggest that all mucosa exposed to the atmosphere, including ocular mucosa, are at risk in dehydrating atmospheres.”

Edwards and the team first looked at whether transpiration, a water loss process that occurs in plants, occurs in mucus of upper airways exposed to dry air environments. High rates of transpiration have proven to cause damaging compression to cells within the leaves of plants, threatening plant survival. The team also sought to see if such compression occurred in upper airway cells.

Researchers exposed cultures of human cells that line the upper airway, known as human bronchial epithelium, to dry air. After exposure, the cells were evaluated for mucus thickness and inflammatory responses. Cells that experienced periods of dry air (with a high VPD) showed thinner mucus and high concentrations of cytokines, or proteins indicating cell inflammation. These results agree with theoretical predictions that mucus thinning occurs in dry air environments and can produce enough cellular compression to trigger inflammation.

The team also confirmed that inflammatory mucus transpiration occurs during normal, relaxed breathing (also called tidal breathing) in an animal model. Researchers exposed healthy mice and mice with preexisting airway dryness, which is common in chronic respiratory diseases, to a week of intermittent dry air. Mice with this preexisting dehydration exhibited immune cells in their lungs, indicating a high inflammatory response, while all mice exposed only to moist air did not.

Based on a climate model study that the team also conducted, they predict that most of America will be at an elevated risk of airway inflammation by the latter half of the century due to higher temperatures and drier air.

Researchers concluded their work by saying these results have implications for other physiological mechanisms in the body, namely dry eye and the movement of water in mucus linings in the eye.

“This manuscript is a game changer for medicine, as human mucosa dehydration is currently a critical threat to human health, which will only increase as global warming continues,” says study co-author Justin Hanes, Ph.D., the Lewis J. Ort Professor of Ophthalmology at the Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins Medicine. “Without a solution, human mucosa will become drier over the years, leading to increased chronic inflammation and associated afflictions.”

“Understanding how our airways dehydrate on exposure to dry air can help us avoid or reverse the inflammatory impact of dehydration by effective behavioral changes, and preventive or therapeutic interventions,” says Edwards.

Collaborators and authors of this research include Aurélie Edwards, Dan Li and Linying Wang of Boston University; Kian Fan Chung of Imperial College London; Deen Bhatta and Andreas Bilstein of Sensory Cloud Inc.; Indika Endirisinghe and Britt Burton Freeman of Illinois Institute of Technology; and Mark Gutay, Alessandra Livraghi-Butrico and Brian Button of University of North Carolina.

***

A portion of this research was funded by NIH grants R01HL125280, P01HL164320 and P30DK065988.

Journal Reference:

Edwards, D.A., Edwards, A., Li, D. et al., ‘Global warming risks dehydrating and inflaming human airways’, Communications Earth & Environment 6, 193 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-02161-z

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Johns Hopkins Medicine

Featured image credit: Freepik