Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press daily roundup, featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

In the heart of vanilla country, farmers on the frontlines of climate change struggle to adapt

As erratic weather upends the seasonal rhythms that crops depend on, farmers in the island nation of Madagascar are feeling the effects but struggle to adapt to the new normal.

That’s one of the key takeaways of a recent survey of nearly 500 small-scale farmers in the country’s northern Sava region, which produces about two thirds of the world’s vanilla beans.

One farmer said she is noticing streams and rivers drying up, making it harder to work the rice paddy that provides the mainstay of her household’s diet. “I am worried about it lasting to the next generation,” she told the research team.

Another, who grows lychees, a small, fleshy fruit, said he can no longer count on the traditional start of the harvest season in November. “Today, we wait until mid-December because of lack of rain,” he said.

They’re not alone. In the new study, published in the journal PLOS Climate, researchers from Duke University and Madagascar’s University of Antananarivo interviewed 479 farmers about the challenges to their livelihood and what they’re doing to cope.

The results were striking.

According to the study, nearly all farmers in the area are experiencing changes in temperature and rainfall that make farming more difficult than it used to be.

They were already struggling to feed their families, the data show. But while most said they expect things to get worse in the future, remarkably few are altering their farming practices to adapt.

That’s according to interviews conducted in 2023 in the villages of Sarahandrano and Mandena, some 50 kilometers apart from each other on the outskirts of Marojejy National Park.

Most people there make a living tending to vanilla beans but also to crops such as rice, bananas and coffee on small plots of land. They use hand tools such as sickles and shovels and water from springs and rivers to care for their crops, some of which they sell in the market. The rest they keep for their own consumption.

But in recent years, locals say they’ve noticed changes in the weather, said senior co-author Charles Nunn of Duke, a professor of evolutionary anthropology and global health who has been working in the area for about a decade.

About three quarters of the survey respondents reported that their water sources were drying up, or said they had to reduce the time spent working their land because of weather extremes such as scorching temperatures or torrential downpours.

The respondents said changing weather brings other problems. Many also reported an uptick in pests such as rodents and mosquitoes in villages and fields or noticed more people getting sick with malaria or diarrhea.

Despite these concerns, only one in five participants said they were taking steps to adapt, such as using fertilizers or mulch to improve soil health or shifting their planting and harvesting calendars for certain crops.

“That is significantly lower than prior studies of climate adaptation among small-scale farmers in other countries,” said Duke Ph.D. student Tyler Barrett, who led the study.

The study revealed that men and people who owned more durable goods, such as a generator or a computer, were more likely to change their practices, suggesting that financial barriers constrain farmers’ ability to take action.

Indeed, some four-fifths of Madagascar’s population lives below the poverty line.

“Many of these alternative farming practices cost the farmers more in labor or materials or both,” said senior co-author Randall Kramer, a professor emeritus of environmental economics and global health at Duke.

Programs and policies aimed at offsetting these costs can help, “particularly for those farmers with less means,” Kramer said. “But we’re just not seeing much of that yet in Madagascar.”

Other changes could improve their options, such as adding fruit trees to fields, or raising fish in flooded rice paddies, said study co-author Voahangy Soarimalala, president of Madagascar’s Vahatra Association and curator at the University of Antananarivo.

These methods can improve food security but also “help with fertilization and pest control,” she added.

Farmers in Madagascar already face numerous risks.

Most are no strangers to cyclones and tropical storms, which can bear down on the island several times a year, uprooting plants and flooding fields with their violent winds and punishing rains — sometimes forcing families to relocate or flee their homes.

During the rainy season, flooded or muddy roads or washed-out bridges can make it harder for people to get their crops to market, Soarimalala said.

Northeast Madagascar isn’t the only region affected.

In the villages around Andringitra, a mountainous national park in southeast Madagascar known for its high peaks and occasional snowfall, elders say they haven’t seen frost in a decade.

Data from 15 weather stations across the country show that average temperatures have grown warmer over the past 50 years, while at the same time average precipitation has decreased.

“It is a serious problem that many farmers worldwide are facing, particularly in tropical areas,” Kramer said.

But small-scale farmers — who produce a third of the world’s food supply — are particularly vulnerable, he added.

As a next step, the researchers are expanding their survey to 34 villages across the region, to see if the patterns they’re seeing so far are confirmed across a wider range of habitats, and to study the impacts of some of the farmers’ adjustments.

“This is just the first of our analyses,” Nunn said.

“Climate change means that farmers are going to have to be more flexible, more resourceful, take more risks,” Kramer said. “That’s really problematic when the success of your farm in a particular year determines if your family goes hungry or not.”

***

Funding was provided by the joint NIH-NSF-NIFA Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Disease Program (R01-TW011493).

Journal Reference:

Barrett TM, Soarimalala V, Pender M, Kramer RA, Nunn CL, ‘Climate Change Perceptions and Adaptive Behavior Among Smallholder Farmers in Northeast Madagascar’. PLOS Climate 4 (3): e0000501 (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pclm.0000501

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Duke University

The boundaries of drainage basins shifted faster during past episodes of climate change, according to a new theory by Ben-Gurion University geologists

Using a unique field site in the Negev, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev geologists have presented the first-ever time-dependent record of drainage divide migration rates.

Prof. Liran Goren, her student Elhanan Harel, and co-authors from the University of Pittsburgh and the Geological Survey of Israel, further demonstrate that episodes of rapid divide migration coincide with past climate changes in the Negev over the last 230,000 years (unrelated to present-day climate change).

It is an astounding achievement that will accelerate our understanding of how climate affects the Earth’s surface.

Their findings were just published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The researchers focused on the migration rate of drainage divides — the topographic boundaries separating neighboring drainage basins. Drainage basins are hydrologic units that accumulate surface water into a single outlet. As divides shift, they reshape basin boundaries and redistribute surface water, rock particles, and ecological niches across landscapes. Until now, the state of the art has been limited to long-term average divide migration rates.

However, a unique site presenting a sequence of terraces in the Negev desert of Israel has provided the first traceable record of divide location at different snapshots in time, constraining a time series of divide migration rate.

Combining field observations, river terrace dating, and numerical simulations, they were able to infer divide migration dynamics in the Negev Desert, over the last 230,000 years. By doing so, they discovered for the first time that episodes of accelerated migration, more than twice the rate of other episodes, coincide with regional climate fluctuations indicated by regional paleoclimate proxies.

“It’s an exciting discovery,” says Prof. Liran Goren of the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, “We were not expecting to discover the correlation with climate fluctuations nor the speed with which the divide shifted during that time. It adds to our knowledge of the drivers affecting the Earth’s surface evolution in fascinating ways.”

“I think what’s fascinating about this research is that a small channel in the Negev desert, which at first glance doesn’t seem particularly remarkable, can actually hold such an impressive record of drainage divide migration along its course,” says Elhanan Harel. “The findings from this study are important for better understanding the nature of divide migration, while also contributing to the ongoing scientific discussion about the climatic history of the Negev.”

Additional researchers include Onn Crouvi and Naomi Porat of the Geological Survey of Israel, Tianyue Qu and Eitan Shelef, of the University of Pittsburgh, and Hanan Ginat of the Dead Sea and Arava Science Center.

***

This research was supported by the United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF), grant number 2019656 and the United States National Science Foundation (NSF-Geomorphology and Land-use Dynamics), grant number 1946253.

Journal Reference:

E. Harel, L. Goren, O. Crouvi, N. Porat, T. Qu, H. Ginat, & E. Shelef, ‘Record of paleo water divide locations reveals intermittent divide migration and links to paleoclimate proxies’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122 (10) e2408426122 (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2408426122

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

Will forests monitor themselves in the future?

“Forests are among the most important ecosystems in nature, constantly evolving, yet their monitoring is often delayed,” says Rytis Maskeliūnas, a professor at Kaunas University of Technology (KTU). Climate change, pests, and human activity are transforming forests faster than we can track them – some changes become apparent only when the damage is already irreversible.

Forest management today is increasingly challenged by environmental changes that have intensified in recent years. “Forests, especially in regions like Lithuania, are highly sensitive to rising winter temperatures. A combination of factors is causing trees to weaken, making them more vulnerable to pests,” says Maskeliūnas.

According to the scientist, traditional monitoring methods such as foresters’ visual inspections or trap-based monitoring are no longer sufficient. “We will never have enough people to continuously observe what is happening in forests,” he explains.

To improve forest protection, KTU researchers have employed artificial intelligence (AI) and data analysis. These technologies enable not only real-time forest monitoring but also predictive analysis, allowing early intervention in response to environmental changes.

Spruce trees are particularly affected by climate change

One key solution is the forest regeneration dynamics model, which forecasts how forests will grow and change over time. The model tracks tree age groups and calculates probabilities for tree transitions from one age group to another by analysing growth and mortality rates.

Head of the Real time computer center (RLKSC), data analysis expert, Prof. Robertas Damaševičius, identifies core advantages of the model: it can identify which tree species are best suited to different environments and where they should be planted.

“It can assist in planning mixed forest replanting to enhance resilience against climate change, as well as predict where and when certain species might become more vulnerable to pests, enabling preventive measures. This tool supports forest conservation, biodiversity maintenance, and ecosystem services by optimising funding allocation and compensation for forest owners,” says Maskeliūnas.

The model is based on advanced statistical methods. The Markov chain model calculates how a forest transitions from one state to another, based on current conditions and probabilistic growth and mortality rates. “This allows us to predict how many young trees will survive or die due to diseases or pests, helping to make more informed forest management decisions,” explains KTU’s Faculty of Informatics professor.

Additionally, a multidirectional time series decomposition distinguishes long-term trends in forest growth from seasonal changes or unexpected environmental factors such as droughts or pest outbreaks. Combining these methods provides a more comprehensive view of forest ecosystems, allowing for more accurate forecasting under different environmental conditions.

The model has also been applied to assess Lithuania’s forest situation, revealing that spruce trees are particularly affected by climate change, becoming increasingly vulnerable due to longer dry periods in summer and warmer winters. “Spruce trees, although they grow rapidly in young forests, experience higher mortality rates in later life stages. This is linked to reduced resistance to environmental stress,” says Maskeliūnas.

Forest sounds reveal ecosystem health

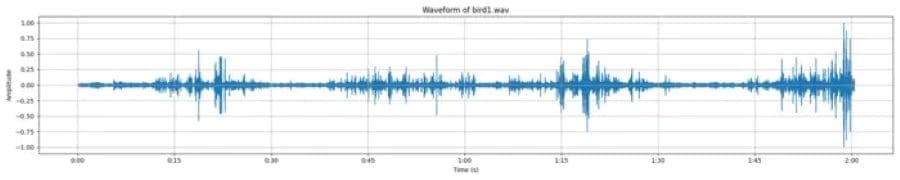

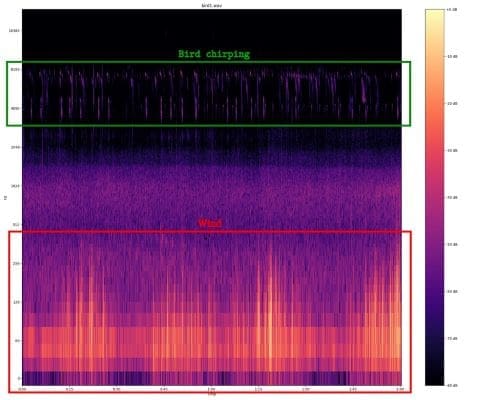

Another tool developed by the researchers is a sound analysis system that can identify natural forest sounds and detect anomalies that may indicate ecosystem disturbances or human activity. Sound analysis is becoming an important part of forest digitisation, allowing real-time environmental monitoring and faster response to potential threats.

The model, proposed by KTU RLKSC PhD student Ahmad Qurthobi, is innovative in combining a convolutional neural network (CNN) with a bi-directional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) model.

“CNN recognises and provides features that describe sound, yet it is not enough to understand how sounds change over time. That’s why we use BiLSTM, which analyses temporal sequences,” explains Maskeliūnas.

This hybrid model not only accurately detects static sounds, such as the constant chirping of birds, but also identifies dynamic changes, such as sudden deforestation noises or shifts in wind intensity.

“For example, bird songs help monitor their activity, species diversity and seasonal changes in migration. A sudden decrease or significant increase in bird sounds can signal ecological problems,” says Maskeliūnas.

Even tree-generated sounds, such as those caused by wind, leaf movement, or breaking branches, can indicate wind strength or structural changes in trees due to drought or other stressors.

Researchers agree that the model could also be adapted for monitoring other environmental changes: “Our model could detect animal sounds such as wolf howls, deer mating calls, or wild boar activity, helping to monitor their movement and behaviour patterns. In urban areas, it could be used to track noise pollution or intensity”.

The solution itself is not just an innovation on paper. The sound analysis system easily integrates into the KTU developed smart forest Internet of Things (IoT) – Forest 4.0.

“The Forest 4.0 IoT devices are like silent guardians of tomorrow’s ecosystems, analysing the heartbeat of our forests in real time and fostering a world where technology listens to nature,” KTU IoT expert Prof. Egidijus Kazanavičius explains.

Currently, some of the models used by foresters tend to oversimplify complex ecological dynamics and fail to consider species competition, environmental feedback loops, and climate variability. As a result, accurately predicting how forests will respond to different factors remains a challenge.

“This is why these advanced technologies represent the future of forest management,” concludes Prof. Maskeliūnas.

Journal Reference:

Damaševičius R, Maskeliūnas R., ‘Modeling Forest Regeneration Dynamics: Estimating Regeneration, Growth, and Mortality Rates in Lithuanian Forests’, Forests 16 (2):192 (2025). DOI: 10.3390/f16020192

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Kaunas University of Technology

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay