Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press daily roundup, featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

Rice University study reveals how rising temperatures could lead to population crashes

Researchers at Rice University have uncovered a critical link between rising temperatures and declines in a species’ population, shedding new light on how global warming threatens natural ecosystems.

The study, published in Ecology and led by Volker Rudolf, revealed that rising temperatures exacerbate competition within populations, ultimately leading to population crashes at higher temperatures. It offers one of the first clear experimental confirmations that rising temperatures alter the forces that control population dynamics in nature.

“Our research provides an essential missing piece in understanding the broader effects of warming on natural populations,” said Rudolf, professor of biosciences. “Even when individual organisms seem to thrive at higher temperatures, the population as a whole may still suffer as competition for resources intensifies.”

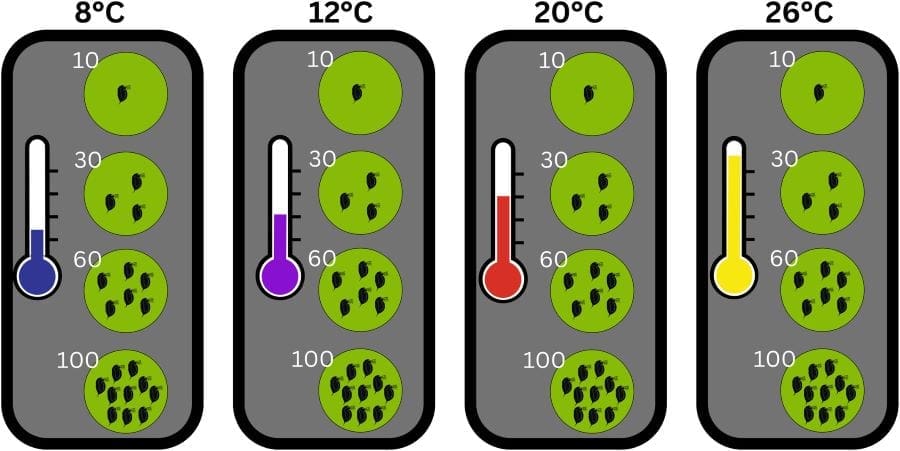

To reveal how temperature influences competition and population growth, the team focused on Daphnia pulex, a small zooplankton species that plays a vital role in freshwater food webs and water quality. By manipulating temperature and population density in a controlled laboratory setting, the researchers isolated the effects of rising temperatures on population dynamics. The results were both fascinating and troubling.

The experiment revealed that competition among the individuals became significantly stronger as temperatures rose. In fact, for every 7 degrees Celsius increase in temperature, competition effects doubled, causing a dramatic 50% population decline at the highest tested temperature. While moderate warming (12-19 °C) initially boosted population growth by accelerating metabolism and reproduction, at higher temperatures these benefits vanished as the increase in competition took its toll, leading to sharp population declines even as individual organisms tolerated the higher temperatures.

“We know warming temperatures increase metabolism and reproduction in ectotherms, but we found that warmer temperatures also create competition that limits survival and reproduction,” said Lillie Stockseth, alumna and first author of the study. Stockseth carried out the experiment as part of her undergraduate senior thesis in Rudolf’s lab and is now working for the Houston Zoo.

“As temperatures rose toward the physiological limit for these populations, increased competition began to outweigh those metabolic benefits and led to population declines. This is an important warning for ecosystems facing rising temperatures — populations could approach decline at less severe temperatures than we’ve thought.”

The findings challenge the assumption that warming always benefits ectotherm populations by boosting individual growth. Instead, they show that rising temperatures can harm populations by intensified competition even before physiological stress becomes a critical factor. This increase in competition can also destabilize populations, further intensifying the risk of local extinctions, especially in environments with frequent temperature fluctuations.

“Our findings suggest that many species could face rapid population declines long before they reach their thermal tolerance limits,” said Zoey Neale, alumna and former graduate student in Rudolf’s lab who now works as a data scientist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. “This has major implications for conservation as it means that temperature-driven population collapses could occur at lower warming thresholds than previously expected and could affect species that were thought to be resilient to temperature changes.”

As global temperatures continue to rise, research like this provides crucial insights that can help predict and mitigate biodiversity loss, a key step to ensuring that vulnerable species and ecosystems receive the protection they need before it’s too late.

Journal Reference:

Stockseth, Lillie, Zoey Neale, and Volker H. W. Rudolf, ‘Strengthening of Negative Density Dependence Mediates Population Decline at High Temperatures’, Ecology 106 (3): e70030 (2025). DOI: 10.1002/ecy.70030

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Alexandra Becker | Rice University

Agriculture is main cause of seasonal carbon ups and downs, study finds

The overall amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has been steadily increasing, a clear trend linked to human activities and climate change. Less concerning but more mysterious, the difference between the highest and lowest amounts of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere each year also has been increasing.

This widening disparity between carbon dioxide peaks and dips was thought to be caused by warming temperatures and more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, but a new study led by Colorado State University has found that agriculture is the primary cause of seasonal carbon cycle swings. This discovery adds to scientific understanding of the carbon cycle and could help inform climate change mitigation strategies.

While climate and carbon dioxide concentrations do contribute to annual carbon cycle highs and lows, the research found that agricultural nitrogen fertilizer is the biggest contributor to fluctuations, highlighting the impact of human actions and land management decisions on Earth system processes.

“These findings are important because we have undervalued the role of agriculture in carbon cycle fluxes,” said lead author Danica Lombardozzi, an assistant professor of ecosystem science and sustainability. “A lot of people recognize that agriculture can help mitigate climate change, but because it’s not represented in most Earth system models, it’s not considered in climate change projections the way it should be.”

Annual carbon cycle fluctuations indicate how much the biosphere is growing every year, Lombardozzi explained. As plants grow in the spring, they draw carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. After crops are harvested and other plants go dormant in the fall, carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increases.

Plants need nitrogen to absorb carbon dioxide and grow. Most crops around the world are fertilized with nitrogen, which is necessary for food production and causes more carbon to be drawn from the atmosphere to fuel greater growth.

The study, published in Nature Communications, found that agricultural nitrogen is responsible for 45% of the fluctuation increase in the annual carbon cycle. More carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and warmer temperatures contribute 40% and 18%, respectively.

The increasing fluctuation driven by crops doesn’t necessarily impact carbon storage, Lombardozzi said, because crops are harvested every year and the carbon they absorb is returned to the atmosphere. However, agricultural management can be adapted to store more carbon in the soil long term, which would help to mitigate climate change.

“Agricultural management practices are very important to shaping the world we live in,” said co-author Gretchen Keppel-Aleks, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Michigan. “At a time when many people feel like climate change has had profound and negative impacts on their lives through wildfire, flooding or droughts, we can use the fact that this study shows that agricultural management has a profound impact on carbon fluxes to think about how we can use agricultural management to our advantage.”

Guided by emerging science, many farmers are adopting practices collectively known as regenerative agriculture to improve soil health and crop production while also mitigating climate change.

Earth system models need to include agriculture

Previous studies have shown that the seasonal difference between high and low concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was increasing but overlooked agriculture’s important role because past versions of Earth system models did not include agricultural processes. Lombardozzi and her co-authors used the Community Earth System Model, developed by the National Center for Atmospheric Research in collaboration with researchers from other institutions, to quantify the sources causing the fluctuation increase and discover that agricultural nitrogen is the most significant factor.

All Earth system models are complex because they encompass global atmospheric, land and ocean processes, including chemistry, biology and physics for the entire planet. The Community Earth System Model is unique because it also incorporates agricultural processes.

Lombardozzi said that Earth system models need to represent agriculture, in particular agricultural nitrogen, to accurately assess the carbon cycle, but most of them currently do not. “It is really hard to represent human decisions in an Earth system model, but we need to tackle it,” she said.

Journal Reference:

Lombardozzi, D.L., Wieder, W.R., Keppel-Aleks, G. et al., ‘Agricultural fertilization significantly enhances amplitude of land-atmosphere CO2 exchange’, Nature Communications 16, 1742 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-56730-z

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Jayme DeLoss | Colorado State University

Tree planting is still the best way to remove carbon – despite climate and economic risks

Tree planting can be the most cost-effective way of removing carbon as long as careful choices are made about which type of trees to plant and where, a new study finds.

Governments worldwide have committed to expand tree cover to remove greenhouse gases, with the UK committing to plant 30,000 hectares of trees each year until 2050.

However, environmental economists point out that there are significant risks of converting farmland to forests comes in a future of climate change and economic uncertainty.

These include the risk of large-scale tree planting displacing agriculture and impacting food security, depending on where it takes place.

In a study published in in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the researchers use the UK as an example to demonstrate that uncertainties about climate change and the economy make the difficult trade-off between carbon removal and agriculture even tricker.

Frankie Cho, a PhD graduate from the University of Exeter and lead author of the study, explains: “One problem is that, because it is unclear what countries round the world will do to tackle climate change – we don’t know how challenging the climate will be in the future. If climate change is extreme, broadleaf trees in southern UK offer the best carbon removal – but that’s prime farmland and could be really costly under certain economic futures.

“If climate change is milder, planting conifers on less productive land makes more sense, but those trees will not grow well if conditions are more extreme. The problem is that we don’t know what the future holds and can’t be certain which type of trees we need to plant and where.”

However, using recent advances in decision-making theory under uncertainty, the researchers show that despite these risks, tree planting can still be the most cost-effective way to remove carbon.

Their study shows that a ‘portfolio’ approach to tree planting – diversifying species and planting locations – helps balances risks and moves beyond planting strategies that simply hope that everything will be ok.

This strategy minimizes the danger of betting on the wrong future, ensuring tree-planting decisions remain resilient in the face of uncertain future climatic and economic conditions.

Importantly, they show that if policymakers adopt these portfolio approaches to tree-planting, it becomes a far more cost-effective strategy for carbon removal than alternatives like biomass energy with carbon capture and storage or direct air capture technologies.

Co-author of the study, Professor Brett Day at the University of Exeter, added: “We don’t have any other option that can remove carbon from the atmosphere at the scale and cost that we need to meet our Net Zero targets. While tree-planting carries risks, our study shows that, if done strategically, it remains the best solution we have.”

Journal Reference:

F.H.T. Cho, P. Aglonucci, I.J. Bateman, C.F. Lee, A. Lovett, M.C. Mancini, C. Rapti, & B.H. Day, ‘Resilient tree-planting strategies for carbon dioxide removal under compounding climate and economic uncertainties’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122 (10) e2320961122 (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2320961122

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Russell Parton | University of Exeter

Intense atmospheric rivers can replenish some of the Greenland Ice Sheet’s lost ice

The Greenland Ice Sheet is the largest ice mass in the Northern Hemisphere, and it’s melting rapidly. Climate change is causing more intense atmospheric rivers, which can deliver intense snowfall — enough to slow Greenland’s ice mass loss, a new study finds.

Atmospheric rivers are bands of water vapor transport that transport moisture and heat from warm oceans to cooler high latitudes. Until recently, they were thought only to exacerbate Arctic ice loss. But in March 2022, an intense atmospheric river delivered 16 billion tons of snow to Greenland. That was enough snow to offset the sheet’s annual ice loss by 8%, the study reports. This massive dump of fresh snow also recharged the winter snowpack with fresh, reflective snow, increasing the snow’s albedo and delaying the onset of ice melt by almost 2 weeks.

Study co-author Alun Hubbard, a field glaciologist at the Universities of Oulu, Finland and the Arctic University of Tromsø, Norway, has worked on the impact of rainfall on Greenland’s ice melt and dynamics for over a decade.

“Sadly, the Greenland Ice Sheet won’t be saved by atmospheric rivers,” Hubbard said. “But what we see in this new study is that, contrary to prevailing opinions, under the right conditions atmospheric rivers might not be all bad news.”

The study was published in Geophysical Research Letters, an open-access AGU journal that publishes high-impact, short-format reports with immediate implications spanning all Earth and space sciences.

Tracing an epic snowstorm

As the Arctic has warmed almost four times faster than the global average since 1980, Greenland has been melting. Warmer temperatures from climate change mean more rain, less snow and more melt, even farther inland, which has historically been the frigid heart of the ice sheet. If the entire Greenland Ice Sheet melts, sea level would rise by more than 7 meters (23 feet).

Atmospheric rivers are expected to become larger, more frequent and more intense in response to climate change, so understanding their impacts on the Greenland Ice Sheet is crucial.

Hannah Bailey, a geochemist at the University of Oulu and the study’s lead author, was working in Svalbard in March 2022 when the intense atmospheric river hit. Heavy rain fell across Svalbard for days, turning winter snowpack into a quagmire and bringing fieldwork to an abrupt halt. Bailey wondered what the storm’s impact was on the Greenland ice sheet.

A year later, Bailey and Hubbard went searching for traces of the storm in southeastern Greenland. There, around 2,000 meters (6,562 feet) above sea level, it’s cold enough that snow accumulates year after year, compressing into denser snow, called firn, and eventually compacting into glacial ice. In this “firn zone,” the researchers dug a deep pit in the snow and collected a 15-meter-long firn core, which captured nearly a decade of snow accumulation. Bailey used oxygen isotopes and the density of different layers to calculate the age profile and snow accumulation rates in the core. She then compared them to local weather and climate data over the same period.

“Using high-elevation firn core sampling and isotopic analysis allowed us to pinpoint the extraordinary snowfall from this atmospheric river,” Bailey said. “It’s a rare opportunity to directly link such an event to Greenland ice sheet surface mass balance and dynamics.”

Atmospheric rivers: Not all bad

The atmospheric river had had pelted Svalbard with rain, but 2,000 kilometers (1,245 miles) away in southeastern Greenland, it delivered snow — and lots of it. On March 14, 11.6 billion tons of snow fell on the ice sheet, with an additional 4.5 billion tons over the next few days. One gigaton of snow roughly equates to one cubic kilometer of fresh water, which could completely fill the U.S. capitol building more than 2,200 times. In a matter of three days, this atmospheric river delivered enough snow to offset Greenland Ice Sheet mass loss by 8% in the 2021-2022 hydrologic year.

“I was surprised by just how much snow was dumped on the ice sheet over such a short period,” Hubbard said. “I thought it’d be a minute amount, but it’s a gobsmacking contribution to Greenland’s annual ice mass.”

By adding so much fresh snow, the atmospheric river delayed the onset of summer ice melt by about 11 days despite warmer than average spring temperatures, the study finds.

More research is needed to understand the net effect of atmospheric rivers on Greenland’s ice in the past and to predict how that may change the in future. If warming continues, all precipitation will eventually fall as rain in Greenland, exacerbating ice loss, Bailey said. “Atmospheric rivers have double-edged role in shaping Greenland’s, as well the wider Arctic’s, futures.”

Journal Reference:

Bailey, H., & Hubbard, A., ‘Snow mass recharge of the Greenland ice sheet fueled by intense atmospheric river’, Geophysical Research Letters 52, e2024GL110121 (2025). DOI: 10.1029/2024GL110121

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Rebecca Dzombak | American Geophysical Union (AGU)

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay