Explore the latest insights from top science journals in the Muser Press daily roundup (January 31, 2025), featuring impactful research on climate change challenges.

In brief:

Groundwater in the arctic is delivering more carbon into the ocean than was previously known

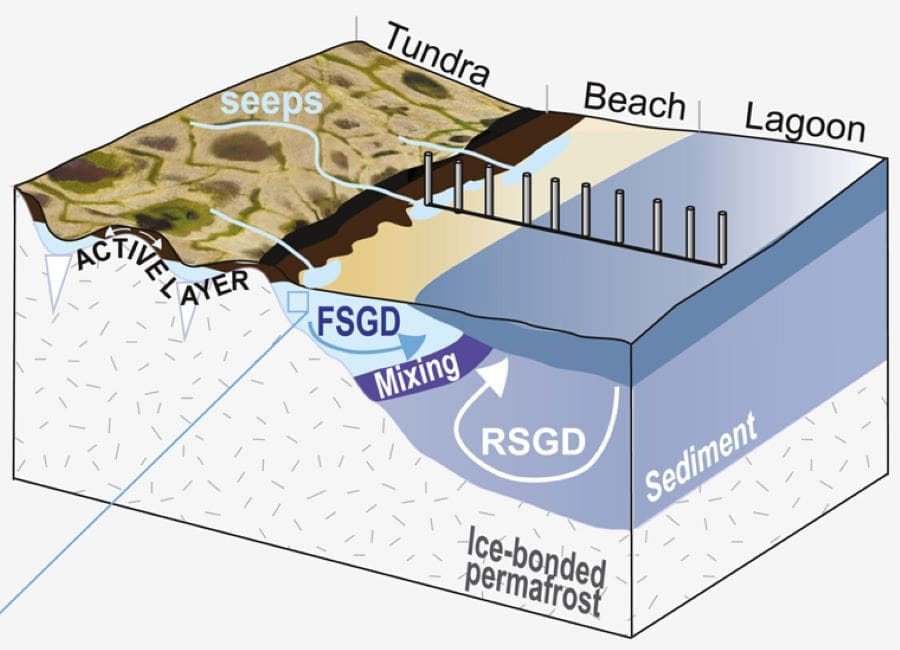

A relatively small amount of groundwater trickling through Alaska’s tundra is releasing huge quantities of carbon into the ocean, where it can contribute to climate change, according to new research out of The University of Texas at Austin.

Researchers found that although the groundwater only makes up a fraction of the water discharged to the sea, it’s liberating an estimated 230 tons of organic carbon per day along the almost 2,000-kilometer coastline of the Beaufort Sea in summer. This quantity of carbon is on par with what free-flowing rivers in the area release during summer months.

“This study shows that there’s humongous amounts of organic carbon and carbon dioxide released via fresh groundwater discharge in summer,” said Cansu Demir, who led the research while she was completing her doctoral degree at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences. She is now a postdoctoral research associate at Los Alamos National Laboratory.

The research was published in Geophysical Research Letters.

As the tundra continues to thaw and the flow of submarine groundwater ratchets up, Demir said that the outflow of carbon from shore to sea could effectively make ocean surface waters a carbon source to the atmosphere. The CO2 released via groundwater could also contribute to ocean acidification.

The study is first to use direct observations to show that fresh water is being discharged into the submarine environment ocean where the coast meets the sea. Before this research, the existence of fresh submarine groundwater discharge in this area of the Arctic was thought to be very limited, Demir said.

The study is also the first to isolate freshwater — which could be made up of rainwater, snow melt, thawed shallow ground ice, and potentially some permafrost thaw — from the total groundwater discharge. Previous studies of groundwater discharge in the Artic included recirculated saltwater, which seeped into the ground from the coast.

Using direct observations, numerical modeling, thermal and hydraulic techniques, researchers found that during the summer, fresh groundwater entering the Beaufort Sea north of Alaska is equal to 3-7% of the total discharge from three major rivers in that area. This volume of water is surprisingly high, according to Demir, who said it’s comparable to fresh groundwater discharge amounts in the temperate regions of lower latitudes. And although the volume of groundwater is proportionally small to the overall river flow, it holds a comparable amount of carbon.

“In that small amount of water, that groundwater carries almost the same amount of organic carbon and nitrogen as rivers,” she said.

Groundwater travels beneath the surface through soils and sediments as it makes its way to the coast, picking up organic matter, inorganic matter, and nutrients on its journey. When it interacts with permafrost, it can receive especially large volumes of carbon. Permafrost is akin to a subterranean estuary – holding large volumes of water and organic matter. When the ice melts and becomes part of the groundwater flow, it can bring a huge quantity of carbon along with it.

“The Arctic coast is changing in front of our eyes,” said Bayani Cardenas, a co-author of this study and professor at the Jackson School’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences. “As permafrost thaws, it turns into coastal and submarine aquifers. Even without this thawing, our studies are among the first to directly show the existence of such aquifers.”

In addition to contributing to global climate change, this huge influx of carbon and nitrogen could have major impacts for Arctic coastal ecology, Demir said. For example, ocean acidification could lead to increased vulnerability of some of the organisms that live on and under the seafloor, such as crustaceans, clams, and snails.

As permafrost continues to thaw under climate change, the amount of freshwater making its way to the sea underground will potentially increase, delivering even more greenhouse gases into coastal waters.

Journal Reference:

Demir, C., McClelland, J. W., Bristol, E., Charette, M. A., & Cardenas, M. B., ‘Coastal supra-permafrost aquifers of the Arctic and their significant groundwater, carbon, and nitrogen fluxes’, Geophysical Research Letters 51, e2024GL109142 (2024). DOI: 10.1029/2024GL109142

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Texas at Austin

Polar bear population decline the direct result of extended ‘energy deficit’ due to lack of food

U of T Scarborough researchers have directly linked population decline in polar bears living in Western Hudson Bay to shrinking sea ice caused by climate change.

The researchers developed a model that finds population decline is the result of the bears not getting enough energy, and that’s due to a lack of food caused by shorter hunting seasons on dwindling sea ice.

“A loss of sea ice means bears spend less time hunting seals and more time fasting on land,” says Louise Archer, a U of T Scarborough postdoc and lead author of the study.

“This negatively affects the bears’ energy balance, leading to reduced reproduction, cub survival and, ultimately, population decline.”

The “bio-energetic” model developed by the researchers tracks the amount of energy the bears are currently getting from hunting seals and the amount of energy they need in order to grow and reproduce. What’s unique about the model is that it follows the full lifecycle of individual polar bears — from cub to adulthood — and compares it to four decades of monitoring data from the Western Hudson Bay polar bear population between 1979 and 2021.

During this period, the polar bear population in this region has declined by nearly 50 per cent. The monitoring data shows the average size of polar bears is also in decline. The body mass of adult females has dropped by 39 kg (86 lbs) and one-year-old cubs by 26 kg (47 lbs) over a 37-year period.

The researchers’ model provides a close match to the monitoring data, meaning it provides an accurate assessment of what is happening and will continue to happen to the polar bear population if it keeps experiencing sea ice loss and a greater amount of time in energy deficit.

“Our model goes one step further than saying there’s a correlation between declining sea ice and population decline,” says Péter Molnár, an associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at U of T Scarborough and co-author of the study.

“It provides a mechanism that shows what happens when there is less ice, less feeding time and less energy overall. When we run the numbers, we get a near one-to-one match to what we’re seeing in real life.”

Polar bear mom and cubs particularly vulnerable

The researchers, which include co-authors from Environment and Climate Change Canada, noted that cubs face the brunt of these climate-induced challenges.

Archer says that shorter hunting periods result in mothers producing less milk, which jeopardizes cub survival. The cubs face reduced survival rates during their first fasting period if they fail to gain enough weight.

Mothers are also having fewer cubs. Monitoring data shows cub litter sizes have dropped 11 per cent compared to almost 40 years ago, and mothers are keeping their cubs longer because they aren’t strong enough to live on their own.

“It’s pretty simple — the survival of cubs directly impacts the survival of the population,” says Archer, whose research is funded through a Mitacs Elevate postdoctoral fellowship and the non-profit organization Polar Bears International.

Broader applications for the model

Western Hudson Bay has long been considered a bellwether for polar bear populations globally, and as the Arctic warms at a rate four times faster than the global average, the researchers warn of similar declines in other polar bear populations.

“This is one of the southernmost populations of polar bears, and it’s been monitored for a long time, so we have very good data to work with,” says Molnár, who is an expert on how global warming impacts large mammals.

“There’s every reason to believe what is happening to polar bears in this region will also happen to polar bears in other regions, based on projected sea ice loss trajectories. This model basically describes their future.”

The study, which is published in the journal Science, received funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Canada Foundation for Innovation.

Journal Reference:

Louise C. Archer et al., ‘Energetic constraints drive the decline of a sentinel polar bear population’, Science 387, 516-521 (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adp3752

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Don Campbell | University of Toronto – Scarborough

Socioeconomic and political stability bolstered wild tiger recovery in India

India, the world’s most populated country, has been successfully working to recover one of the largest, and most iconic, carnivores, the tiger, for decades. Protection, prey, peace, and prosperity have been key factors in the tiger recovery within this densely populated country, according to a new study.

According to its authors, success in India offers a rare opportunity to explore the socio-ecological factors influencing tiger recovery more broadly. Earth’s large carnivores, crucial for maintaining ecosystem health, are among the most threatened species, impacted by habitat loss, prey depletion, human conflict, and illegal exploitation.

These apex predators – vital for maintaining trophic cascades and ecosystem health – face diminishing populations, particularly in developing regions, where challenges like habitat fragmentation and high poverty compound conservation and recovery efforts.

Tigers, once widespread across Asia, had been eliminated from over 90% of their historic range, leaving only about 3,600 wild individuals by the early 21st century. In response, tiger-range countries launched the Global Tiger Recovery Program in 2010 with the goal of doubling tiger populations by 2022. Despite hosting some of the densest human populations on Earth, India achieved this target and is now home to roughly 75% of the world’s wild tigers.

Drawing on 20 years of extensive national-scale tiger monitoring data, Yadvendradev Jhala and colleagues analyzed 381,000 square kilometers (km²) of tiger habitats using advanced occupancy models and high-resolution spatial datasets. The findings show that tigers have increased their range by nearly 3,000 km² annually over the past 2 decades, with a large portion of their current territory (45%) shared with ~60 million people in India.

Protected areas, abundant with prey species, played a vital role in providing refuge, allowing tigers to repopulate surrounding multi-use landscapes. However, regions affected by high poverty, armed conflict, and habitat loss saw continued absence of tigers and localized extinctions, underscoring the importance of socioeconomic and political factors in ensuring successful recovery.

“The success of tiger recovery in India offers important lessons for tiger-range countries as well as other regions for conserving large carnivores while benefitting biodiversity and communities simultaneously,” write Jhala et al. “It rekindles hope for a biodiverse Anthropocene.”

Journal Reference:

Yadvendradev V. Jhala et al., ‘Tiger recovery amid people and poverty’, Science 387, 505-510 (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adk4827

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)

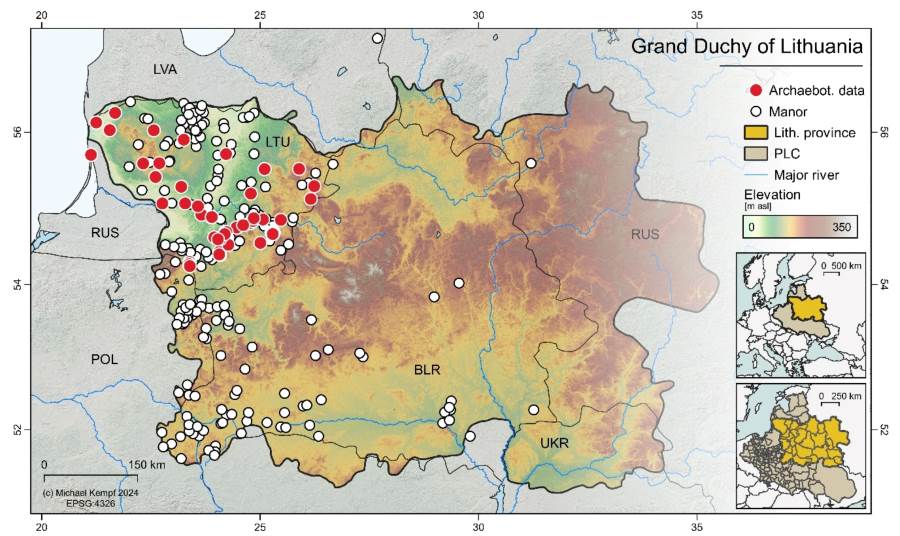

Ancient agricultural strategies revealed: how pre-industrial communities adapted to climate changes

A new study, published in Scientific Reports, provides insights into the resilience and ingenuity of ancient agricultural systems, emphasizing the dynamic interplay between environmental challenges and human innovation. By analyzing archaeological evidence and historical records, the researchers reconstructed past crop repertoires, shedding light on how communities diversified their agriculture to ensure food security amidst changing conditions.

This research enhances our understanding of historical agricultural practices and offers valuable lessons for modern agriculture. As contemporary societies face greater climate variability and socioeconomic uncertainties, the adaptive strategies of the past may inform sustainable agricultural practices and policies today.

“Recent drying-up processes and increased risk of prolonged heatwaves and subsequent droughts are challenging our socio-political resilience, and demand a rethinking of global food production strategies. Reconsidering drought tolerant species, therefore, can help mitigate the long-term effects of current global warming,” says environmental scientist Dr. Michael Kempf.

“It is due to the Little Ice Age that the staple foods such as rye bread and buckwheat porridge came to dominate the cuisine of northeastern Europeans. Warming climates might lead us back to forgotten millet crops,” says Prof. Motuzaite Matuzeviciute.

Situated at the intersection of different climatic zones, northeastern Europe represents a marginal agricultural region where buffer crops play a crucial role in ensuring food security amidst shifting environmental conditions.

“Natural conditions, agriculture, and gastronomic culture have always been closely interconnected. Gastronomic culture is more inert, meaning that environmental changes first affected agriculture and only later became apparent in the kitchen. Therefore, studying these processes is essential for understanding both past and contemporary societies.” noted Prof. Rimvydas Laužikas.

The historical records indicate a southward shift of millet agriculture during the onset of the Little Ice Age. The Vilnius University PhD candidate Meiirzhan Abdrakhmanov concludes that “this study emphasizes the dynamic nature of agricultural adaptation and underscores the resilience of past communities in responding to climatic changes.”

Journal Reference:

Abdrakhmanov, M., Kempf, M., Karaliute, R. et al., ‘The shifting of buffer crop repertoires in pre-industrial north-eastern Europe’, Scientific Reports 15, 3720 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-87792-0

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Vilnius University

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay