Paris, France | AFP

The world’s largest iceberg — a behemoth more than twice the size of London — is drifting toward a remote island where scientists say it could run aground and threaten penguins and seals.

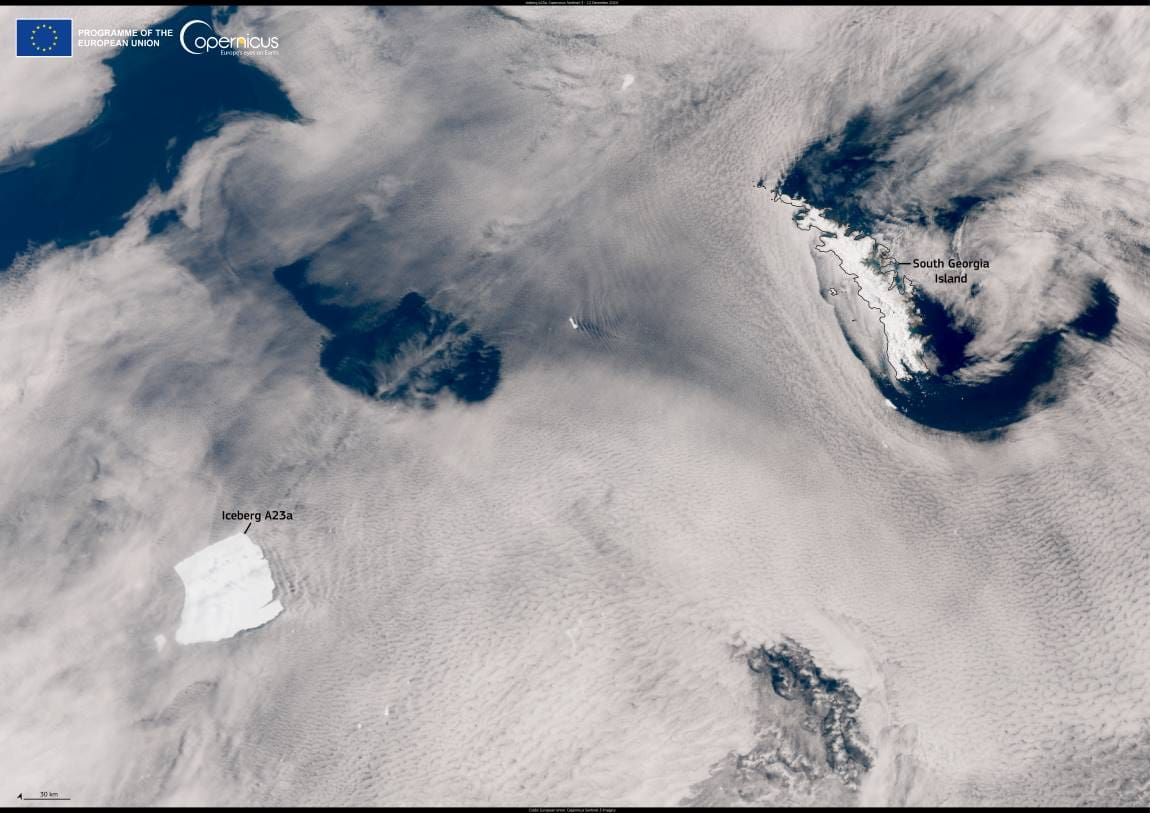

The gigantic wall of ice is moving slowly from Antarctica on a potential collision course with South Georgia, a crucial wildlife breeding ground.

Satellite imagery suggested that unlike previous “megabergs” this rogue was not crumbling into smaller chunks as it plodded through the Southern Ocean, Andrew Meijers, a physical oceanographer at the British Antarctic Survey, told AFP on Friday.

He said predicting its exact course was difficult but prevailing currents suggested the colossus would reach the shallow continental shelf around South Georgia in two to four weeks.

But what might happen next is anyone’s guess, he said.

It could avoid the shelf and get carried into open water beyond South Georgia, a British overseas territory some 1,400 kilometres (870 miles) east of the Falklands Islands.

Or it could strike the sloping bottom, getting stuck for months or break up into pieces.

Meijers said this scenario could seriously impede seals and penguins trying to feed and raise their young on the island.

“Icebergs have grounded there in the past and that has caused significant mortality to penguin chicks and seal pups,” he said.

‘White wall’

Roughly 3,500 square kilometres (1,550 square miles) across, the world’s biggest and oldest iceberg known as A23a calved from the Antarctic shelf in 1986.

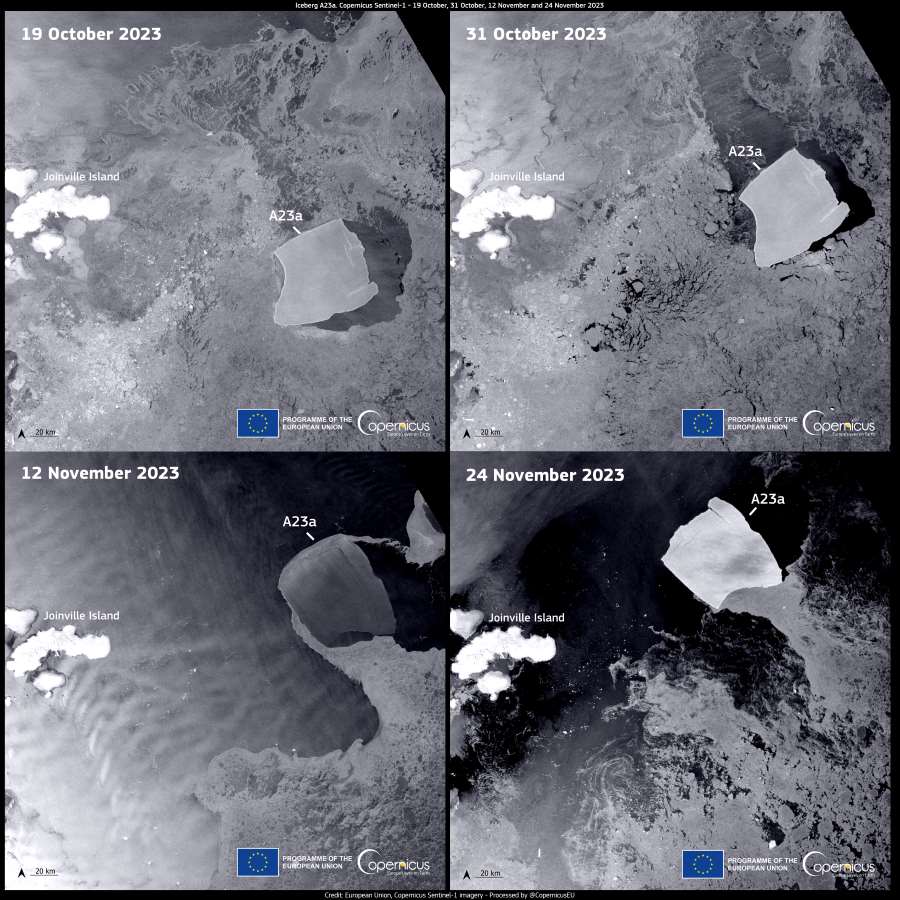

It remained stuck for over 30 years until finally breaking free in 2020, its lumbering journey north sometimes delayed by ocean forces that kept it spinning in place.

Meijers — who encountered the iceberg face to face while leading a scientific mission in late 2023 — described “a huge white cliff, 40 or 50 metres high, that stretches from horizon to horizon”.

“It’s just like this white wall. It’s very sort of Game of Thrones-esque, actually,” he said, describing “feeling like it would never end”.

A23a has followed roughly the same path as previous massive icebergs, passing the east side of the Antarctica Peninsula through the Weddell Sea along a route called “iceberg alley”.

Weighing a bit under a trillion tonnes, this monster block of freshwater was being whisked along by the world’s most powerful ocean “jet stream” — the Antarctic Circumpolar Current.

Meijers said that was tracking “more or less a straight line from where it is now to South Georgia” where waters quickly turn shallow and the current bends sharply.

The iceberg could follow that current out to sea or run aground the shelf, he said.

Icy obstacle

It is summer in South Georgia and resident penguins and seals along its southern coastline are undertaking foraging expeditions in the frosty waters to bring back enough food to fatten their young.

“If the iceberg parks there, it’ll either block physically where they feed from, or they’ll have to go around it,” said Meijers.

“That burns a huge amount of extra energy for them, so that’s less energy for the pups and chicks, which causes increased mortality.”

The seal and penguin populations on South Georgia have already been having a “bad season” with an outbreak of bird flu “and that (iceberg) would make it significantly worse,” he said.

“It would be fairly tragic, but it’s not unprecedented.”

As A23a ultimately melted it could litter the ocean with small — but still hazardous — chunks of ice difficult for fishermen to navigate, Meijers added.

It would also seed the water with nutrients that encourage phytoplankton growth, feeding whales and other species, and allowing scientists to study how such blooms absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

While icebergs were very natural phenomena, Meijers said the rate at which they were being lost from Antarctica was increasing, likely due to human induced climate change.

np-mpr/

© Agence France-Presse

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Nick Perry | AFP

Featured image credit: European Union, Copernicus Sentinel-3 imagery