New research sheds light on rapidly warming regions in the Arctic-boreal zone, revealing areas of intense ecological stress.

The study, published in Geophysical Research Letters, identifies hotspots of climate vulnerability in Siberia, Alaska, and the Canadian Northwest Territories, where ecosystems are undergoing some of the fastest and most extreme changes on the planet.

The research team, composed of scientists from Woodwell Climate Research Center, the University of Oslo, the University of Montana, the Environmental Systems Research Institute (Esri), and the University of Lleida, analyzed over three decades of geospatial data and temperature records. By integrating multiple indicators—temperature, moisture, and vegetation—scientists uncovered a comprehensive view of climate impacts across the region.

“Climate warming has put a great deal of stress on ecosystems in the high latitudes, but the stress looks very different from place to place, and we wanted to quantify those differences,” said Dr. Jennifer Watts, Arctic program director at Woodwell Climate and lead author of the study.

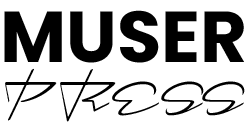

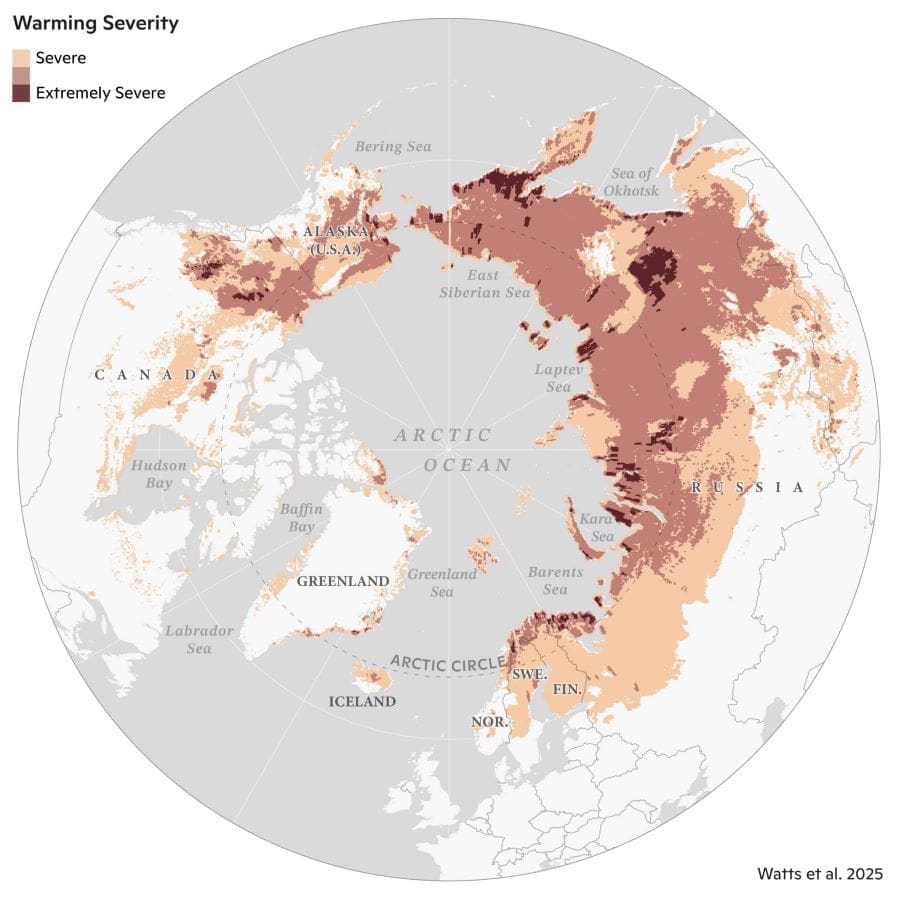

Among the most impacted areas were those with permafrost — ground that remains frozen year-round — where severe warming and drying trends have been observed. The findings indicate significant warming across approximately 99% of Eurasian tundra between 1997 and 2020, with the most intense warming detected in eastern and central Siberia. In contrast, only 72% of Eurasian boreal forests experienced warming during the same period.

Regions in Alaska and central Canada showed increased surface water and flooding, potentially driven by thawing permafrost.

“The Arctic and boreal regions are made up of diverse ecosystems, and this study reveals some of the complex ways they are responding to climate warming,” explained Dr. Sue Natali, lead of the Permafrost Pathways project at Woodwell Climate. “However, permafrost was a common denominator — the most climate-stressed regions all contained permafrost, which is vulnerable to thaw as temperatures rise. That’s a really concerning signal.”

To pinpoint vulnerable regions, the team utilized spatial statistics, which highlighted local “neighborhoods” of elevated climate change impacts. The approach provided a detailed picture of changes at a localized scale, offering land managers actionable insights.

“This study is exactly why we have developed these kinds of spatial statistic tools in our technology,” said Dr. Dawn Wright, chief scientist at Esri. “We are so proud to be working closely with Woodwell Climate on identifying and publishing these kinds of vulnerability hotspots that require effective and immediate climate adaptation action and long-term policy.”

The study’s findings highlight the need for tailored climate adaptation strategies. Just as Covid-19 tracking data proved more actionable when examined locally, hotspot mapping offers similar advantages in addressing ecological and climate challenges. Regional data can guide management practices and adaptation plans that reflect the specific needs of different ecosystems.

According to Watts, the vulnerability of Siberian boreal forests — critical carbon sinks — should serve as a global warning. “These forested regions, which have been helping take up and store carbon dioxide, are now showing major climate stresses and increasing risk of fire. We need to work as a global community to protect these important and vulnerable boreal ecosystems, while also reining in fossil fuel emissions.”

As the Arctic continues to warm at unprecedented rates, studies like this underline the urgent need for informed, localized actions to preserve ecosystems critical to the planet’s climate stability.

Journal Reference:

Watts, J. D., Potter, S., Rogers, B. M., Virkkala, A.-M., Fiske, G., Arndt, K. A., et al. ‘Regional Hotspots of Change in Northern High Latitudes Informed by Observations From Space’, Geophysical Research Letters 52, e2023GL108081 (2025). DOI: 10.1029/2023GL108081

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Woodwell Climate Research Center

Featured image credit: Christina Shintani | Woodwell Climate Research Center