A widening economic divide is shaping how agricultural climate policies influence food prices globally, with stark differences between wealthy and poor nations.

A study by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), published in Nature Food, reveals that in high-income countries, value-added components like processing and marketing shield consumers from sharp food price increases. Meanwhile, in low-income nations, where farming costs dominate food prices, consumers face greater financial strain from climate mitigation policies. These contrasting dynamics expose the vulnerabilities of low-income countries to the growing impacts of climate change and the policies designed to address it.

PIK – Farmers are receiving less of what consumers spend on food, as modern food systems increasingly direct costs toward value-added components like processing, transport, and marketing.

A new study by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) shows that this effect shapes how food prices respond to agricultural climate policies: While value-added components buffer consumer price changes in wealthier countries, low-income countries – where farming costs dominate – face greater challenges in managing food price increases due to climate policies.

“In high-income countries like the U.S. or Germany, farmers receive less than a quarter of food spending, compared to over 70 percent in Sub-Saharan Africa, where farming costs make up a larger portion of food prices,” says David Meng-Chuen Chen, PIK scientist and lead author of the study published in Nature Food. “This gap underscores how differently food systems function across regions.”

The researchers project that as economies develop and food systems industrialise, farmers will increasingly receive a smaller share of consumer spending, a measure known as the ‘farm share’ of the food dollar.

“In wealthy countries, we increasingly buy processed products like bread, cheese or candy where raw ingredients make up just a small fraction of the cost,” adds Benjamin Bodirsky, PIK scientist and author of the study. “The majority of the price is spent for processing, retail, marketing and transport. This also means that consumers are largely shielded from fluctuations in farm prices caused by climate policies such as taxes on pollution or restrictions on land expansion, but it also underscores how little farmers actually earn.”

Examining the full food value chain to uncover climate policy impacts

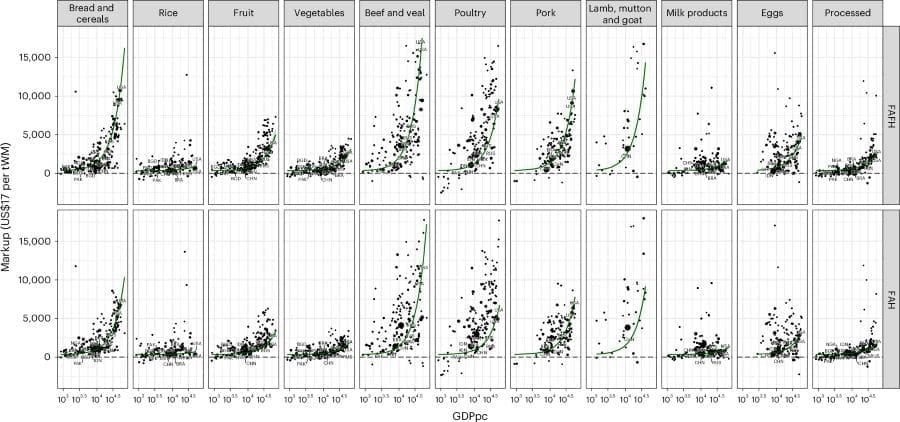

To arrive at these conclusions, the team of scientists combined statistical and process-based modelling to assess food price components across 136 countries and 11 food groups. They studied prices of food both consumed at home and away from home.

“Most models stop at farm costs, but we went all the way to the grocery store and even the restaurant or canteen,” says Chen. By analysing the entire food value chain, the researchers also provide new insights into how greenhouse gas mitigation policies impact consumers. “Climate policies aimed at reducing emissions in agriculture often raise concerns about rising food prices, particularly for consumers. Our analysis shows that long supply chains of modern food systems buffer consumer prices from drastic increases, especially in wealthier countries,” explains Chen.

“Even under very ambitious climate policies with strong greenhouse gas pricing on farming activities the impact on consumer prices by the year 2050 would be far smaller in wealthier countries,” Bodirsky says.

Consumer food prices in richer countries would be 1.25 times higher with climate policies, even if producer prices are 2.73 times higher by 2050. In contrast, lower-income countries would see consumer food prices rise by a factor of 2.45 under ambitious climate policies by 2050, while producer prices would rise by a factor of 3.3. While even in lower-income countries consumer price rises are less pronounced than for farmers, it would still make it harder for people in lower-income countries to afford sufficient and healthy food.

Climate policies essential for safeguarding agriculture and food systems in the long run

Despite food price inflation, poor consumers do not necessarily need to suffer from climate mitigation policies. A previous study by PIK (Soergel et al 2021) showed that if revenues from carbon pricing were used to support low-income households, these households would be net better off despite food price inflation, due to their higher incomes.

“Climate policies might be challenging for consumers, farmers, and food producers in the short term, but they are essential for safeguarding agriculture and food systems in the long run,” says Hermann Lotze-Campen, Head of Research Department ‘Climate Resilience”’ at PIK and author of the study.

“Without ambitious climate policies and emission reductions, much larger impacts of unabated climate change, such as crop harvest failures and supply chain disruptions, are likely to drive food prices even higher. Climate policies should be designed to include mechanisms that help producers and consumers to transition smoothly, such as fair carbon pricing, financial support for vulnerable regions and population groups, and investments in sustainable farming practices.”

Journal Reference:

David Meng-Chuen Chen, Benjamin Bodirsky, Xiaoxi Wang, Jiaqi Xuan, Jan Philipp Dietrich, Alexander Popp, Hermann Lotze-Campen, ‘Future food prices will become less sensitive to agricultural market prices and mitigation costs’, Nature Food (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s43016-024-01099-3

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK)

Featured image credit: Freepik