The factors behind the shifting trends of ischemic heart disease and stroke

Incidence of stroke and ischemic heart disease are declining around the world, except for in a handful of regions, according to research published in PLOS Global Public Health.

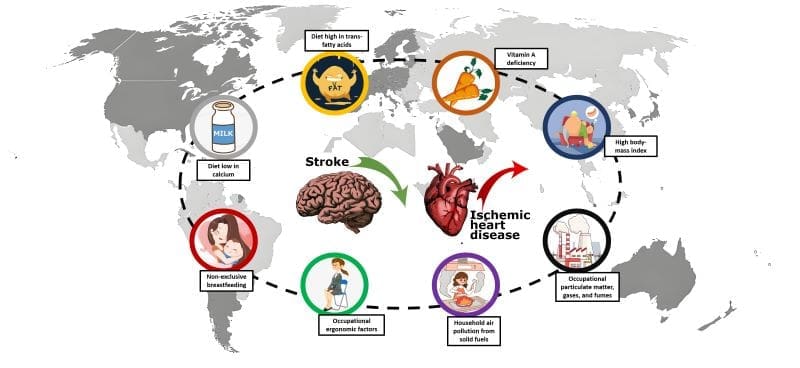

Wanghong Xu of Fudan University and colleagues find that in East and West Sub-Saharan Africa, East and Central Asia and Oceania, ischemic heart disease is increasing, which may be attributed to eight factors that include diet, high BMI, household air pollution and more.

Cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide, and ischemic heart disease and stroke accounted for 16% and 11% of total deaths in 2019 respectively. Over time both have decreased in incidence, but the distribution of this decline varies and in some regions there is an upward trend.

The team analyzed global data from 1990-2019 for incidence of ischemic heart disease and stroke and for exposure to 87 potential attributable factors. The authors describe the incidences and trends at a global, regional and national level, and find higher rates of ischemic heart disease than stroke.

Over three decades ischemic heart disease reduced from 316 to 262 per 100,000 people and stroke declined from 181 to 151 per 100,000.

The increases of ischemic heart disease seen in some regions may be associated with the shifting distribution of eight factors: a diet high in trans-fatty acids; diet low in calcium; high BMI; household air pollution from solid fuels; non-exclusive breastfeeding; occupational ergonomic factors; vitamin A deficiency; and, occupational exposure to particulate matter, gases and fumes, which were determined by the World Bank income levels.

The results indicate how the potential socioeconomic development of some countries is affecting rates of cardiovascular disease and stroke, and that places experiencing rapid economic transitions – and rapidly changing lifestyle changes – may also be experiencing higher rates of disease. This study and provides insight into mechanisms involved and the potential for targeted interventions.

The authors add: “This study profiles the significantly different incidence trends of ischemic heart disease and stroke across countries, identifies eight potential contributors to the disparities, and reveals the pivotal role of socioeconomic development in shaping the country-level associations of the risk factors with the incidences of the two cardiovascular diseases.”

Journal Reference:

Xia R, Cai M, Wang Z, Liu X, Pei J, Zaid M, et al. ‘Incidence trends and specific risk factors of ischemic heart disease and stroke: An ecological analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease 2019’, PLOS Glob Public Health 4 (11): e0003920 (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0003920

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by PLOS

Mixed forests reduce the risk of forest damage in a warmer climate

Forests with few tree species pose considerably higher risk of being damaged and especially vulnerable is the introduced lodgepole pine. This is shown in a new study by researchers from Umeå University and the Swedish University of Agricultural Science in Uppsala.

The results can be useful for preventing forest damages and financial losses related to the forest industry.

Fungi, insects, fires and cervids, such as moose, are examples of natural factors behind tree damages in Swedish forests. Sometimes, the damages become so extensive that they impact the function of forest ecosystems, not least the ability of forests to provide wood and other tree products.

“In a warmer climate with more extreme weather and new pest organisms, and with a more intense forestry, forest damages are expected to become more common and more severe. It is therefore important to understand causes of forest damages and whether it can be prevented,” says researcher Micael Jonsson at Umeå University, who led the study.

The Swedish national forest inventory has collected extensive data from Swedish forests. Since 2003, data on forest damages have also been collected.

In the current study, the research group has analyzed 15 years of these data from all over Sweden, to investigate which damages are most common and which factors determine the risk of a tree becoming damaged. The study is more extensive both in time and geographically than previous studies.

The results show that wind and snow are the most common causes of tree damage, followed by forestry and then fungi. Damages from cervids – mostly moose – are on fifth place. 94 percent of all trees showed some kind of damage. Coniferous trees and young stands showed the highest risk of damage, and in warmer parts of Sweden, stands with few tree species showed a considerably higher risk of being damaged compared to stands with a higher number of tree species.

“Our results show that there is a potential to reduce the risk of forest damages via a changed forest management. Especially, a higher proportion of broadleaf trees in the otherwise so coniferous-dominated production forest would result in fewer damages. We can for example see that the lodgepole pine, introduced by the forestry industry, has the highest risk of damage. Its introduction therefore counteracts a profitable forestry,” says Micael Jonsson.

The results also indicate that a higher number of tree species in a stand act as an insurance against extensive forest damages in a warmer climate.

“We must adapt Swedish forests and forest management methods to a future warmer climate. Including more tree species in production forests seems to be an adaptation that could work!” says co-author Jan Bengtsson at the Swedish University of Agricultural Science.

However, the study also shows that the data material has some weaknesses. For example, it has not been possible to establish the cause behind a large proportion of the damages.

“The national forest inventory collects important data for our understanding of the forest, but when it comes to the damage inventory, the data quality needs to improve to be fully usable in forestry practices,” says Jon Moen, co-author at Umeå University.

Journal Reference:

Micael Jonsson, Jan Bengtsson, Jon Moen, Tord Snäll, ‘Tree damage risk across gradients in tree species richness and stand age: Implications for adaptive forest management’, Ecosphere 15 (11) e70071 (2024). DOI: 10.1002/ecs2.70071

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Umeå University | Sara-Lena Brännström

Climate change and air pollution could risk 30 million lives annually by 2100

New study projects a sharp rise in temperature- and pollution-related mortality, with the impact of temperature surpassing that of pollution for a fifth of the global population.

The researchers base their calculations on projections from 2000 to 2090, analyzed in ten-year intervals.

“In 2000, around 1.6 million people died each year due to extreme temperatures, both cold and heat. By the end of the century, in the most probable scenario, this figure climbs to 10.8 million, roughly a seven-fold increase. For air pollution, annual deaths in 2000 were about 4.1 million. By the century’s close, this number rises to 19.5 million, a five-fold increase,” explains Dr. Andrea Pozzer, group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz and adjunct associate professor at The Cyprus Institute in Nicosia, Cyprus.

The study shows significant regional differences in future mortality rates. South and East Asia are expected to face the strongest increases, driven by aging of the population, with air pollution still playing a major role. In contrast, in high-income regions – such as Western Europe, North America, Australasia, and Asia Pacific – deaths related to extreme temperatures are expected to surpass those caused by air pollution.

In some countries within these regions, such as the United States, England, France, Japan and New Zealand, this shift is already occurring. The disparity is likely to grow, with extreme temperatures becoming a more significant health risk than air pollution also in countries of Central and Eastern Europe (e.g. Poland and Romania) and parts of South America (e.g. Argentina and Chile).

By the end of the century, temperature-related health risks are expected to outweigh those linked to air pollution for a fifth of the world’s population, underscoring the urgent need for comprehensive actions to mitigate this growing public health risk.

“Climate change is not just an environmental issue; it is a direct threat to public health,” says Andrea Pozzer. “These findings highlight the critical importance of implementing decisive mitigation measures now to prevent future loss of life,” adds Jean Sciare, director of the Climate and Atmosphere Research Center (CARE-C) of The Cyprus Institute, key contributor to the study.

Journal Reference:

Pozzer, A., Steffens, B., Proestos, Y. et al. ‘Atmospheric health burden across the century and the accelerating impact of temperature compared to pollution’, Nature Communications 15, 9379 (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-53649-9

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Max Planck Institute for Chemistry

Florida manatees flourish and flounder alongside human neighbors

Historic accounts reveal manatee populations increased in the 1800s and 1900s alongside human populations.

Florida manatees are threatened by human activity, but they’re also doing better than ever, according to a study examining manatee populations since 12,000 BC, published in PLOS ONE by Thomas J. Pluckhahn of the University of South Florida and David K. Thulman of George Washington University, Washington DC, U.S.

Florida manatees are an iconic species and also a conservation concern, threatened by environmental change and watercraft collisions.

Historical manatee populations are poorly understood, and therefore little is known about the state of manatees before modern human influence, making it difficult for conservationists to set goals for establishing healthy manatee populations.

In this study, the authors investigate manatee populations between 12,000 BC and the mid-20th century by compiling records of manatee remains from archaeological sites as well as historical accounts of manatee sightings from newspapers, journals, and other sources.

The data indicates that manatees were quite rare during most of this time period before increasing in population size and distribution during the 1800s and 1900s, coincident with increasing human populations.

This population growth is likely related to expanded conservation laws, improved public perception of manatees, and warming water temperatures due to climate change and power plant construction.

Despite their modern reputation as a rare species, these results suggest that Florida manatees are more abundant today than any previous time in North American human history.

Many of the anthropogenic changes that endanger the species today are also likely responsible for their population growth over the past two centuries. The authors note that manatee conservation goals cannot simply aim for a return to pre-modern population conditions, and that a detailed understanding of their history and ecological relationship with humans will be necessary to establish healthy conservation goals.

The authors add: “Manatees are among Florida’s most iconic species, so the possibility that they were not common here until the modern era is surprising. There is a lot of uncertainty regarding changes the Anthropocene will bring in the future, as human-caused climate change accelerates. But our study serves as a reminder that we don’t even fully understand the changes that have already occurred across the modern era. We think there are lessons from that history which might be helpful for managing a better future for both people and manatees in Florida.”

Journal Reference:

Pluckhahn TJ, Thulman DK, ‘Historical ecology reveals the “surprising” direction and extent of shifting baselines for the Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostis)’, PLoS ONE 19 (11): e0313070 (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0313070

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by PLOS

Growing soybeans has a surprisingly significant emissions footprint, but it’s ripe for reduction

Over the typical two-year rotation of corn and soybeans most Iowa farmers use, 40% of nitrous oxide emissions are in the soybean year, according to a new study by an Iowa State University research team.

The share of the potent greenhouse gas released during the soybean half of a crop rotation cycle is surprisingly high, given most soybeans fields aren’t treated with nitrogen, said Michael Castellano, agronomy professor and William T. Frankenberger Professor of Soil Science at Iowa State University.

“We’ve just been assuming that legume crops like soybeans don’t have a big emissions footprint because they don’t usually receive fertilizer. But the natural processes in soil that produce nitrous oxide don’t stop just because you don’t apply fertilizer,” Castellano said. “Nearly half of our emissions in a typical cropping system come from soybeans, and we haven’t even been thinking about how to manage them.”

A team led by Castellano and postdoctoral researcher Tomas Della Chiesa hopes to change that. In a paper about the new analysis published in Nature Sustainability, they also shared modeling that shows planting winter cover crops in the fall and soybeans earlier in the spring could reduce emissions by one-third while increasing yields.

“My favorite part of this research is farmers are more likely to implement these solutions right away because they’re practical and scalable. The options already exist, but people just aren’t thinking about them in this way,” Castellano said.

An inherent challenge

In most industries, technology exists to slow or stop the release of heat-trapping gases causing climate change, such as carbon dioxide. Agriculture has a tougher and inherent challenge. Its greenhouse impact comes largely from methane and nitrous oxide, emissions that are difficult to curb because they’re biological byproducts. Livestock digestion is the biggest source of methane, while soil management is the main culprit for nitrous oxide.

“If you’re going to grow crops, there’s going to be some greenhouse gas emissions,” Castellano said.

It makes sense that most of the attention devoted to emissions from Corn Belt fields has been on optimizing nitrogen fertilizer usage, said Castellano, who also leads the Iowa Nitrogen Initiative, an ongoing research project to give Iowa farmers more precise data on ideal nitrogen rates. Properly managing fertilizer use is the essential first step in reducing emissions in corn-soybean systems and has other environmental benefits, such as improving water quality.

But fertilizer isn’t the only source of nitrous oxide in farming. When microbes break down organic matter in soil, some of the nitrogen produced converts into a gas form. Without plants to use the nitrogen generated in decomposition, bare soil gives off higher amounts of nitrous oxide – especially in the spring, when warmth and moisture encourage microbial activity. That’s what causes most soybean emissions.

“It’s coming from biochemical processes we can’t do anything to stop,” Della Chiesa said.

Limiting bare farmland

To quantify how much soybean farming contributes to the nitrous oxide output of the upper Midwest’s dominant crop rotation, Della Chiesa and Castellano analyzed data from 16 prior studies of corn-soybean systems. Finding that 40% of emissions came during the soybean half of the rotation heightens the need for a broader range of mitigation options, Della Chiesa said.

“We have to be thinking about management practices that aren’t related to fertilizer,” he said. “Half the year, we have bare soil.”

A strategy the researchers studied in their paper would drastically shorten the time farmland spends without living plants. Aerially sowing a winter cover crop of oats or rye into mature corn fields would cover soil with plants for the months between crops, and using an extended-growth soybean variety would allow earlier spring planting. The two-prong method would reduce soybean-year emissions by 33% and, with planting moved up about four weeks, increase yields by 16%, based on crop-system modeling.

Extended-growth soybeans are already widely available, and farmers are increasingly pushing soybean planting earlier. But they usually prioritize corn in the spring because corn yields are more affected by a late start than soybean yields. It helps that the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 2023 moved up by about a week the earliest planting date for soybeans covered by federal crop insurance. Soybeans in most of Iowa are covered if planted on or after April 15, while corn across Iowa and soybeans in southern Iowa are covered on or after April 10.

In the future, federal officials should consider the environmental benefits of setting earlier planting dates for insurance coverage, Castellano said.

“Our work suggests earlier planting has some value that should be incorporated when making those decisions,” he said.

What’s next?

The United Soybean Board provided the primary funding for the research and is also supporting a three-year follow-up study to field test the emissions and yield impact of combining a corn-following cover crop and earlier soybean planting, Castellano said. Results at experimental plots in Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota and Kentucky have been promising.

Other Iowa State research is seeking ways to capitalize on the advantages of earlier planting. Castellano and Matthew Hufford, a professor of ecology, evolution and organismal biology at Iowa State, are involved in a study exploring the emissions impact of earlier corn planting. And several Iowa State breeding experts are studying ways to genetically improve crops to be more tolerant of early-season cold.

No matter the approach, it’s crucial to identify ways to limit nitrous oxide production in agriculture, Castellano said. Though it currently represents a sliver of global greenhouse emissions, nitrous oxide on a pound-for-pound basis traps about 300 times more heat than carbon dioxide, and its relative influence on climate change will likely rise in the coming years.

“As we decarbonize other economic sectors, emissions from agriculture as a proportion of global emissions are expected go up rapidly because the mitigation opportunities are few and limited. So we need these reduction strategies,” Castellano said.

Journal Reference:

Della Chiesa, T., Northrup, D., Miguez, F.E. et al. ‘Reducing greenhouse gas emissions from North American soybean production’, Nature Sustainability (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41893-024-01458-9

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Iowa State University

Featured image credit: Gerd Altmann | Pixabay