As the UN Climate Change Conference (COP 29) opens on November 11, a significant debate looms over how industrialized nations will fulfill their financial commitments to assist poorer countries in addressing climate change. While the specifics of how these contributions will be raised remain uncertain, a new study suggests that taxing the windfall profits from oil and gas companies could offer a potential solution.

The international team of researchers, including experts from the Technical University of Munich (TUM), has revealed that the windfall profits generated by the global oil and gas sector due to the 2022 energy crisis could have covered nearly five years’ worth of the climate financing commitments made by industrialized nations.

These countries had promised to deliver $100 billion annually from 2020 to 2025 to support climate protection and adaptation efforts in developing nations. However, these commitments have largely gone unmet, and discussions on the follow-up agreement – the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) – have yet to resolve how additional funding will be raised.

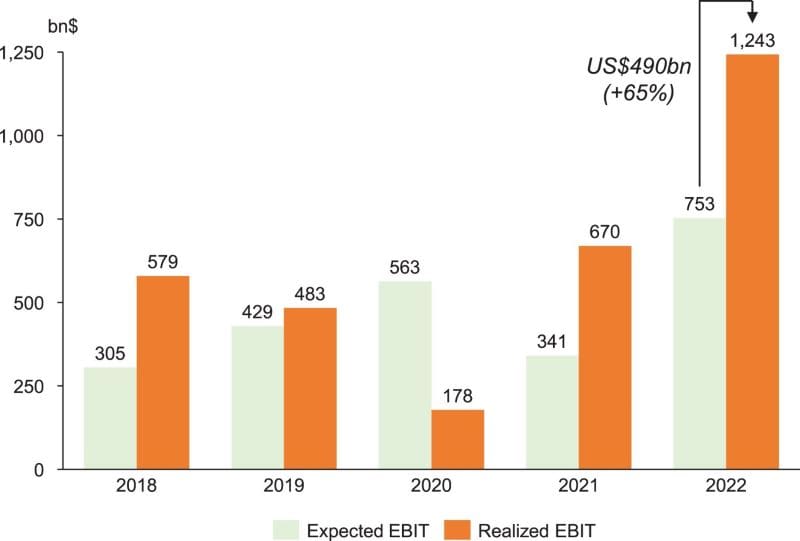

The researchers focused on profits reported by 93 of the world’s largest oil and gas companies for the year 2022, comparing them to the initial forecasts made by analysts at the start of the year. The expected profits amounted to approximately $753 billion, but actual profits surged to about $1.243 trillion. This resulted in a $490 billion windfall – funds that, according to study leader Florian Egli, could easily cover the climate finance promises for nearly five years.

A global crisis amplified by profits

The study highlights that the energy crisis precipitated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 contributed to an extraordinary surge in international energy prices. This situation led to what is commonly referred to as “windfall profits” – profits that exceeded expectations due to abnormal conditions. For example, state-controlled oil companies earned 42% of these windfall profits, with Norway’s state-owned company being a notable contributor. The findings underscore the capacity of governments to levy taxes on such profits, using the funds to address climate challenges.

Dr. Anna Stünzi, second study leader and a researcher at the University of St. Gallen, pointed out that governments of countries housing state-owned oil and gas companies could take direct action to collect these additional profits. “The governments have the ability to take direct action to skim off the profits earned due to a crisis and use them to fight the climate crisis,” she said.

Opportunities for taxing superprofits

The research also revealed that 95% of the private companies reaping these windfall profits are based in countries that have committed to climate protection financing. In particular, companies headquartered in the USA accounted for roughly half of the windfall profits (around $143 billion), with additional profits concentrated in the UK, France, and Canada. Almost all of these companies are located in G20 nations, which are also the primary contributors to global emissions.

The study’s authors argue that taxing these windfall profits could help industrialized nations generate funds to meet their climate financing obligations. “At least some industrialized countries could generate income to meet their commitments to the poorer countries,” said Florian Egli.

While the idea of taxing these profits might face political challenges, Egli points to the recent agreement among more than 130 countries on a global minimum corporate tax rate as a potential model. The introduction of a similar tax on windfall profits could provide a stable source of funding for climate action, even in years without such exceptional profits.

The European Union has already introduced a temporary windfall profit tax for fossil fuel companies, and the UK has extended its tax until 2030.

Redirecting fossil fuel profits for climate goals

The study also notes that the actual profits of the oil and gas industry likely exceed the figures included in their analysis, as many of the world’s largest companies – particularly those in countries like Russia, Iran, South Africa, and Venezuela – do not disclose their profits.

Michael Grubb, a professor at University College London (UCL) and co-author of the study, emphasized that redirecting superprofits could not only help raise the necessary funds but also encourage the transition toward a clean energy future.

“Taxing superprofits could tamper and phase down investment in oil and gas, building a stable and efficient clean energy market and helping to align financial flows with the goals of the Paris Agreement,” Grubb said.

As COP 29 discussions unfold, this research provides a compelling argument for rethinking how fossil fuel profits could be used to combat climate change, potentially setting the stage for a new era of financial cooperation between the world’s wealthiest nations and those most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

Journal Reference:

Egli, F., Grubb, M., & Stünzi, A, ‘Harnessing oil and gas superprofits for climate action‘, Climate Policy 1–8 (2024). DOI: 10.1080/14693062.2024.2424516

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Technical University of Munich (TUM)

Featured image credit: rorozoa | Freepik.com