Climate change is rewriting the rulebook for drought in the American West, where higher temperatures are transforming what might otherwise be mild droughts into severe, water-sapping events.

A study led by climate scientists from UCLA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reveals that evaporative demand, or the atmosphere’s pull on moisture from soil, plants, and water bodies, is now a greater driver of drought than reduced rainfall itself.

This shift could mean more frequent, widespread droughts across the western U.S. even if precipitation levels remain stable.

In their research, recently published in Science Advances, the scientists found that 61% of the drought intensity experienced from 2020 to 2022 was due to increased evaporation, while only 39% stemmed from a reduction in rainfall.

“Research has already shown that warmer temperatures contribute to drought, but this is, to our knowledge, the first study that actually shows that moisture loss due to demand is greater than the moisture loss due to lack of rainfall,” said Rong Fu, a UCLA professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences and corresponding author of the study.

Historically, droughts in the West were driven mainly by dry weather and low rainfall. But climate change, fueled by greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels, is complicating this pattern by heating the atmosphere to levels where it draws significant moisture from the environment.

According to NOAA’s National Integrated Drought Information System Executive Director Veva Deheza: “This study further confirms we’ve entered a new paradigm where rising temperatures are leading to intense droughts, with precipitation as a secondary factor.” Deheza’s observations point to a troubling new trend in water availability for the region.

The study explains that as the atmosphere warms, it can hold more water vapor, preventing condensation needed for rainfall. This can create a drought cycle: warmer temperatures increase evaporation rates, causing more water to be drawn from soils and reservoirs into the atmosphere, but much of that moisture never returns as rain. As a result, droughts now persist longer, cover larger areas, and reduce soil moisture levels more severely as the climate heats up.

The researchers analyzed over 70 years of data to separate droughts caused by natural weather variations from those intensified by human-driven climate change. They found that since 2000, 80% of the increase in evaporative demand is linked to climate change, with that figure rising to 90% during extreme droughts.

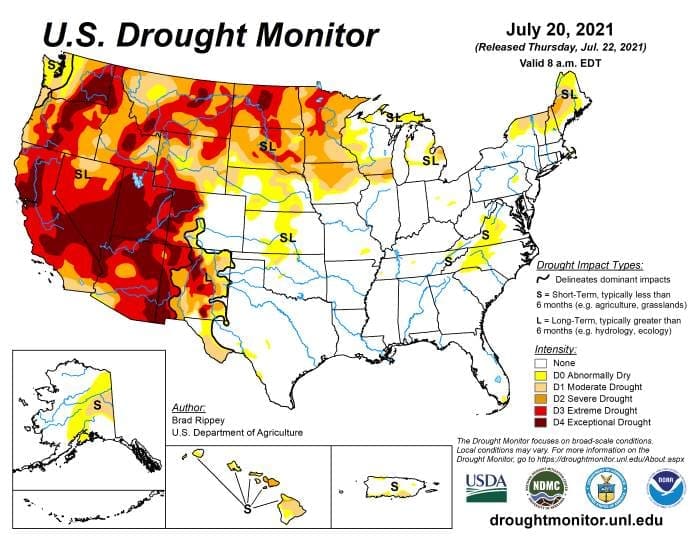

“During the drought of 2020–2022, moisture demand really spiked,” Fu noted. “Though the drought began through a natural reduction in precipitation, I would say its severity was increased from the equivalent of ‘moderate’ to ‘exceptional’ on the drought severity scale due to climate change.”

To understand the historical scope of these changes, researchers compared drought conditions from the 1948-1999 period with those from 2000 onward. Since the turn of the century, the area affected by droughts has expanded by 17%, and evaporative demand alone could cause drought in 66% of drought-prone regions, compared to just 26% before 2000.

Additional climate model simulations in the study paint a stark picture of the future. If greenhouse gas emissions continue, droughts on the scale of the 2020-2022 drought, which would normally occur once in a thousand years, could become events seen every 60 years by the mid-21st century and every six years by its end.

“Even if precipitation looks normal, we can still have drought because moisture demand has increased so much, and there simply isn’t enough water to keep up with that increased demand,” Fu said. With no way to prevent evaporative demand from rising in warmer temperatures, Fu concludes that the only solution is to halt further warming by reducing emissions.

Journal Reference: Yizhou Zhuang et al. ‘Anthropogenic warming has ushered in an era of temperature-dominated droughts in the western United States’, Science Advances 10, 45, eadn9389 (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adn9389

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of California – Los Angeles

Featured image credit: Andrew Innerarity | California Department of Water Resources