A new study, published in Nature Communications Earth & Environment, suggests that while global temperatures are undoubtedly rising, there is no statistically significant evidence to support a recent surge in the rate of global warming.

The research, led by a team from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in collaboration with a statistician from Lancaster University, confirms a steady warming trend rather than a sharp acceleration over the past 50 years.

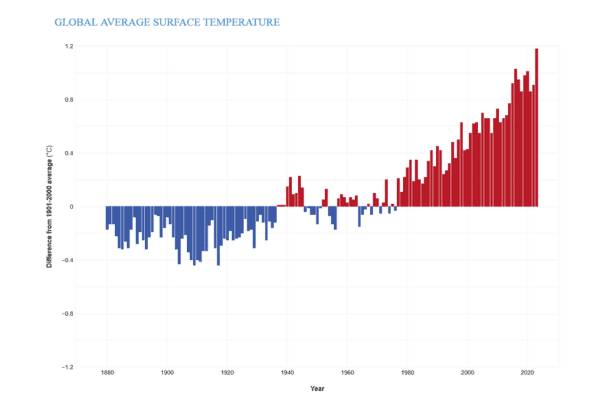

The study comes at a time when record-setting heat waves are becoming more frequent worldwide. Data show that 2023 was the warmest year on record since 1850, and that the 10 warmest years have all occurred within the last decade. This trend has sparked debates over whether global warming has intensified in recent years.

However, the study’s lead author, Professor Claudie Beaulieu, cautions against misinterpreting recent extreme temperatures as evidence of a sudden increase in the rate of global warming.

“We’ve had these record-breaking temperatures recently, but that’s not necessarily inconsistent with steadily increasing global warming,” said Beaulieu, Professor of Ocean Sciences at UC Santa Cruz. “Of course, it is still possible that an acceleration in global warming is occurring. But we found that the magnitude of the acceleration is either statistically too small, or there isn’t enough data yet to robustly detect it.”

Analyzing global temperature trends

The research team conducted an extensive analysis of global mean surface temperature (GMST) data collected by four major agencies, including NASA and NOAA, with records dating back to 1850. The analysis revealed a 0.11-degree Fahrenheit (0.061-degree Celsius) per decade rise in global temperature over this period.

The GMST (global mean surface temperature) is a crucial metric in climate science, but it also presents significant challenges.

As Rebecca Killick, Professor of Statistics at Lancaster University and co-author of the study, noted, the GMST is influenced by both human-driven warming and natural variations such as major volcanic eruptions and El Niño events. This natural variability can obscure the long-term warming trend, making it difficult to detect any statistically significant surges.

To address this challenge, the researchers established a threshold for what would constitute a statistically detectable surge. According to the study, for a surge to be detected, the warming rate would need to increase sufficiently and sustain that higher rate over an extended period.

For instance, the team determined that if the warming rate in 2012 had increased by 55%, it would have been detectable by 2024. Similarly, a 35% change in 2010 would be detectable by 2035.

“We decided to address this head on, using all commonly used statistical approaches and comparing their results,” Killick explained. “Our concern with the current discussion around the presence of a ‘surge’ is that there was no rigorous statistical treatment or evidence.”

One of the key contributions of the study is a benchmark that can guide future research on global warming surges. The researchers provided minimum percentage increases in warming rates required for statistical detectability up to the year 2040.

“Alongside our results, we give a benchmark to scientists, a minimum threshold that must be exceeded before a change may be detectable,” said Killick. “We hope this helps add rigour to future discussions on potential surges or hiatus.”

While the study found no statistical evidence of an accelerating warming rate, it reinforces the reality of a warming planet. Beaulieu emphasizes that these findings do not dispute climate change; instead, they underscore the steady, ongoing rise in global temperatures due to human activity.

“Earth is the warmest it has ever been since the start of the instrumental record because of human activities—and to be clear, our analysis demonstrates the ongoing warming,” Professor Beaulieu said. “However, if there’s an acceleration in global warming, we can’t statistically detect it yet.”

Journal Reference:

Beaulieu, C., Gallagher, C., Killick, R. , Lund R., Shi X., ‘A recent surge in global warming is not detectable yet’, Nature Communications Earth & Environment 5, 576 (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-024-01711-1

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by Lancaster University

Featured image credit: Freepik