A new study by researchers at the University of Hawaiʻi’s Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) suggests that curtailing carbon emissions could be key to helping coral reefs adapt and survive climate change.

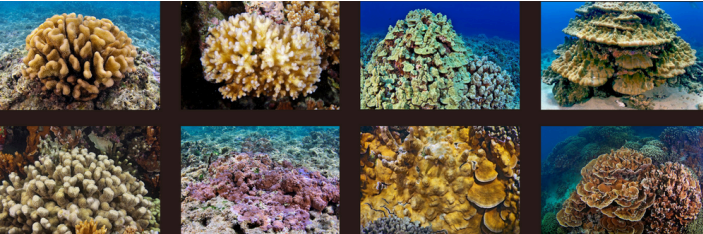

Published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, the research identifies conditions under which eight prevalent coral species in Hawaiʻi can withstand warming oceans and acidification.

Coral reefs, particularly those in the Indo-Pacific region, which accounts for over two-thirds of the world’s coral reefs, are increasingly vulnerable to rising ocean temperatures and changing pH levels due to carbon dioxide emissions.

The study demonstrates that these coral species are capable of surviving a “low climate change scenario,” where global carbon dioxide emissions are significantly reduced. However, under a “business-as-usual” scenario with continued high emissions, none of the coral species were found to have the capacity to survive. This conclusion highlights the critical role that climate change mitigation must play in preserving coral reefs globally.

“This study shows that widespread and diverse coral species all exhibit the potential to adapt to the changing climate, but climate change mitigation is essential for them to have a chance at adaptation,” said Christopher Jury, HIMB post-doctoral researcher and lead author of the study. He emphasized that while none of the species are likely to survive if the current trajectory of emissions continues, all eight coral species examined have the potential to adapt under the lower emissions scenario envisioned by the Paris Climate Agreement.

Coral reefs are formed through a process known as coral calcification, where individual coral polyps create skeletons by secreting calcium carbonate, which hardens into limestone. This growth is slow, with some colonies growing less than an inch per year, making them highly sensitive to environmental changes.

The research team at HIMB’s Toonen-Bowen “ToBo” Lab used biologically diverse, semi-enclosed outdoor environments called ‘mesocosms’ to simulate real-world conditions. Over nearly a year, the researchers monitored how different levels of temperature and acidity affected the calcification rates of eight key coral species.

Rob Toonen, a professor at HIMB and the project’s principal investigator, explained: “About one quarter to one half of their tolerance is inherited through their genes. That means the ability to survive under future ocean conditions can be passed along to future generations, allowing corals to adapt to ocean warming and acidification.”

Previous projections for the future of coral reefs, particularly in Hawaiʻi and other regions heavily impacted by climate change, have been grim. Many experts have warned that coral reefs could collapse within decades due to their inability to keep pace with rapidly changing ocean conditions. This study provides a glimmer of hope, suggesting that coral adaptation is possible under the right conditions.

“This was a very surprising result, given the usual projected collapse of coral reefs in Hawaiʻi and globally under these climate change stressors,” said Jury. “Most projections are that corals will be almost entirely wiped out, and coral reefs will collapse within the next few decades because corals cannot adapt fast enough to make a meaningful difference. This study shows that is not true, and we still have an opportunity to preserve coral reefs.”

Coral reefs are not only crucial for marine biodiversity but also for human populations. They provide food, income, and coastal protection for over half a billion people globally. In addition to offering habitat for thousands of marine species, coral reefs act as natural barriers against storms and coastal erosion, support fisheries, and contribute to tourism. They are also a source of novel compounds for medicine.

Despite their ecological importance, most studies on coral resilience have focused on heat tolerance, with far fewer addressing their ability to adapt to ocean acidification or the combination of both stressors. This new study marks a significant step forward in understanding how coral species can respond to these dual challenges.

By examining how these eight common coral species in Hawaiʻi, which make up about 95% of the coral cover on the state’s reefs, respond to climate change, the study provides valuable insights for future conservation efforts.

Jury noted: “By understanding how these species respond to climate change, we have a better understanding of how Hawaiian reefs will change over time and how to better allocate resources as well as plan for the future.”

While the study offers hope, it also underscores the urgency of global action to reduce carbon emissions. The ability of coral reefs to survive the coming decades hinges on the decisions made today, particularly those that affect the rate of climate change.

Journal Reference:

Jury Christopher P. and Toonen Robert J. ‘Widespread scope for coral adaptation under combined ocean warming and acidification’, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 291: 20241161 (2024). DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2024.1161

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

Featured image: Porites evermanni Credit: Keoki Stender