A recent study conducted by researchers from the University of Southern California (USC) and Australia reveals a troubling finding: even firm believers in climate science can start doubting their convictions after being exposed repeatedly to climate-skeptical claims.

The study, published in PLOS ONE, underscores the insidious power of repetition in swaying beliefs, regardless of their foundation in scientific truth.

The study focuses on a psychological phenomenon known as the ‘illusory truth effect‘, where repeated exposure to a statement makes it seem more truthful, regardless of its factual accuracy. The researchers sought to determine how this effect influences those who strongly support climate science when they are presented with claims that contradict their beliefs.

The results show that even those categorized as “alarmed” believers – individuals with the highest levels of concern about climate change – could perceive climate-skeptical statements as more truthful simply due to repetition.

Norbert Schwarz, co-author of the study and Provost Professor of Psychology at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, highlighted the dangerous implications of this effect: “It could take as little as a single repetition to make someone feel as though a claim were true. It’s certainly concerning, especially when you consider how many people are exposed to both truthful and false claims and either spread them or are persuaded by them to make decisions that might affect the planet.”

Testing the strength of convictions

The research was conducted in two rounds, involving 52 participants in the first and 120 in the second. Of these, 90% were strong supporters of climate science, while less than 10% expressed skepticism about climate change.

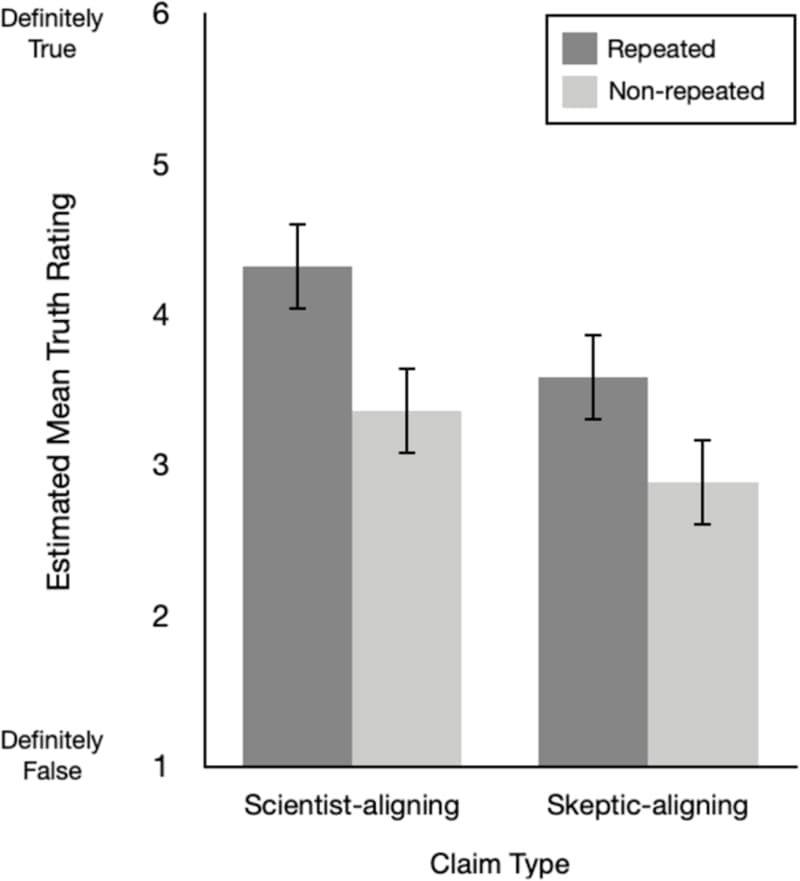

The study participants were asked to rate the truth of various statements, some of which were climate-skeptical, others supportive of climate science, and a few that were neutral weather-related statements.

The key finding was that even the strongest climate science believers rated the repeated claims, whether aligned with their beliefs or not, as more valid. This shift was particularly striking among the “alarmed” group, who previously demonstrated the highest levels of belief in human-caused climate change.

As Mary Jiang, the lead author of the study from The Australian National University, explained: “People find claims of climate skeptics more credible when they have been repeated just once.”

Repeated exposure to false claims can blur the lines between truth and fiction, even for those who consider themselves well-informed. This effect, sometimes referred to as “truthiness,” occurs because repetition makes information feel familiar, and familiar information is more likely to be believed, regardless of its accuracy.

Schwarz emphasized the importance of this finding: “This study emphasizes what we have learned over the years, and that is: We should not repeat false information. Instead, we must repeat what is true so that it becomes familiar and more likely to be believed.” This insight is crucial in the context of climate change, where misinformation can have far-reaching consequences for public policy and individual behavior.

Implications for climate communication

The study’s findings hold significant implications for how climate science is communicated. While repetition is a valuable tool for reinforcing positive, science-based messages, it can also amplify misinformation. Schwarz noted that repetition can be beneficial when promoting truthful, constructive actions, such as healthy behaviors or sustainable practices. However, when false beliefs are repeated, they gain unwarranted credibility, which can undermine efforts to address climate change.

In an era where information – both true and false – spreads rapidly through social media and other channels, the study highlights the importance of careful communication strategies. Climate scientists and advocates need to ensure that accurate information is consistently reinforced to counteract the influence of misinformation.

The research provides a reminder of how vulnerable even the most committed climate science believers can be to misinformation. The ‘illusory truth effect‘ demonstrates that repeated exposure to false or misleading statements can cause individuals to doubt scientifically-supported facts, including the reality of human-driven climate change.

***

Read another article about this study on Muser Press here.

Journal Reference:

Jiang Y, Schwarz N, Reynolds KJ, Newman EJ, ‘Repetition increases belief in climate-skeptical claims, even for climate science endorsers’. PLOS ONE 19 (8): e0307294 (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0307294

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Southern California

Featured image credit: Freepik (AI Gen)