A new study by researchers at the University of Leeds has unveiled the vast scale of uncollected waste and open burning of plastic as primary contributors to the global plastic pollution crisis.

Published in Nature, the study presents the first global inventory of plastic pollution, revealing alarming data on the extent of the issue and identifying new hotspots of plastic waste emissions.

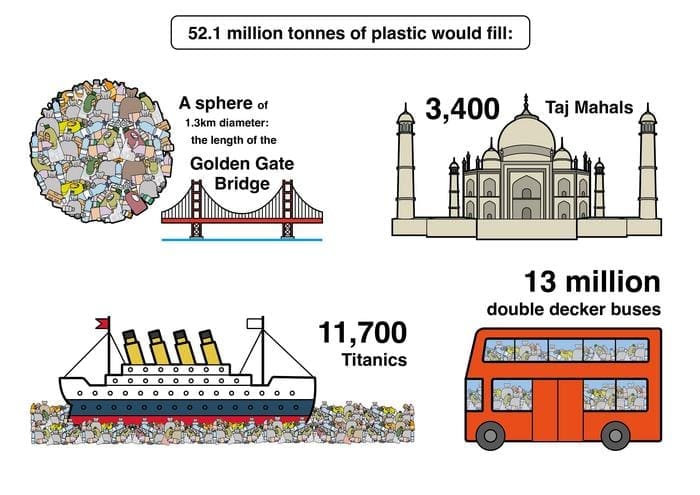

Utilizing artificial intelligence (AI), the research team modeled waste management practices in over 50,000 municipalities worldwide. Their findings indicate that in 2020 alone, approximately 52 million metric tons of plastic entered the environment. This amount of plastic, if laid out end-to-end, would encircle the planet more than 1,500 times.

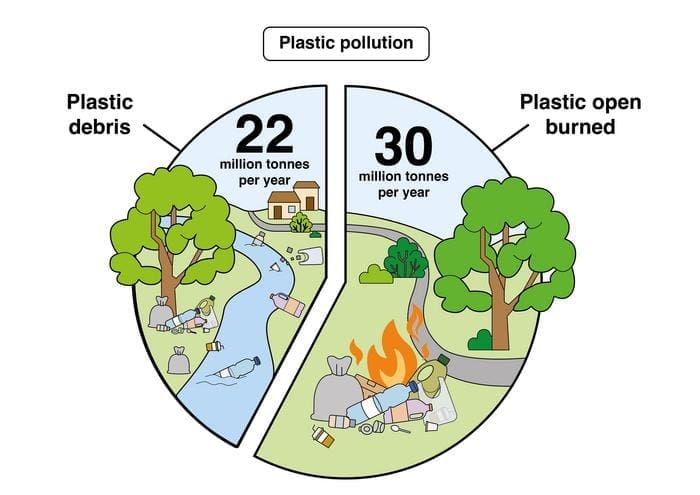

The study highlights that over two-thirds of this plastic pollution originates from uncollected rubbish, with nearly 1.2 billion people – 15% of the global population – lacking access to waste collection services. This deficiency forces millions to dispose of waste by dumping it on land, in rivers, or burning it in open fires, posing significant health risks.

One of the study’s key revelations is the scale of open burning, which accounted for about 57% of all plastic pollution in 2020. Around 30 million metric tons of plastics were burned without environmental controls, releasing harmful toxins that threaten human health. Dr. Costas Velis, who led the research, stressed the urgency of addressing this issue, stating: “We need to start focusing much, much more on tackling open burning and uncollected waste before more lives are needlessly impacted by plastic pollution.”

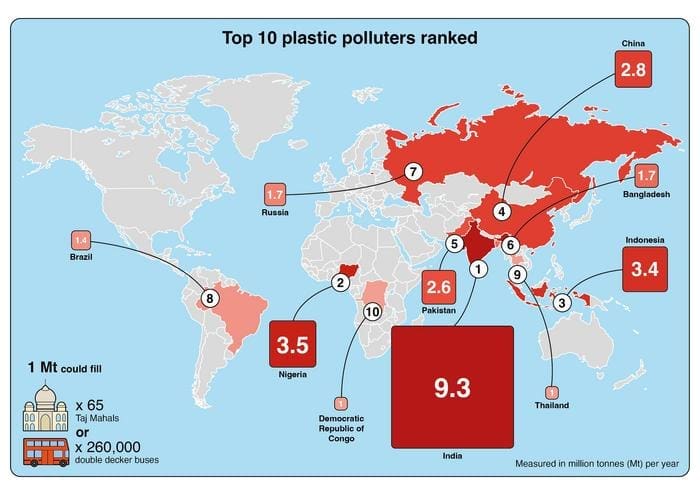

The study also challenges previous assumptions about the sources of plastic pollution. While China has long been considered the world’s largest contributor, the new inventory identifies India as the leading polluter, followed by Nigeria and Indonesia. Improvements in waste collection and processing in China have reduced its contribution, now ranking it fourth.

The researchers emphasize the stark contrast between plastic waste emissions in the Global North and South.

High-income countries, despite their significant plastic consumption, produce relatively low macroplastic pollution due to effective waste management systems. In contrast, low and middle-income countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, face growing challenges. With an average of 12 kilograms of plastic pollution per person per year, the region could become a major source of global plastic pollution in the coming decades.

The study’s authors argue that access to waste collection should be considered a basic necessity, alongside water and sanitation services. They call for a globally coordinated response, including the establishment of a legally binding international “Plastics Treaty” informed by scientific data. This treaty, they suggest, would help governments allocate resources effectively to combat plastic pollution and protect public health.

Dr. Costas Velis, an academic of Resource Efficiency Systems from the School of Civil Engineering at Leeds, led the research. He concluded: “This is an urgent global human health issue – an ongoing crisis: people whose waste is not collected have no option but to dump or burn it; setting the plastics on fire may seem to make them ‘disappear’, but in fact the open burning of plastic waste can lead to substantial human health damage including neurodevelopmental, reproductive and birth defects.”

The study provides a crucial baseline for future efforts to mitigate the environmental and health impacts of plastic waste.

Journal Reference:

Cottom, J.W., Cook, E. & Velis, C.A., ‘A local-to-global emissions inventory of macroplastic pollution’, Nature 633, 101–108 (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07758-6

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of Leeds

Featured image credit: Tom Fisk | Pexels