Valley fever, a fungal disease caused by Coccidioides spores, has seen a dramatic rise in cases across California, U.S. in recent decades.

A new study, published in The Lancet Regional Health – Americas, by researchers from the University of California San Diego and University of California, Berkeley, highlights the seasonal patterns and the influence of drought on the disease’s spread. The findings offer critical insights for public health strategies as climate change intensifies.

Rising Valley Fever cases in California

Valley fever primarily affects individuals who inhale airborne spores from disturbed soil, often leading to flu-like symptoms. However, the disease can escalate to severe complications, including damage to the respiratory system and, in extreme cases, spread to the brain, which can be fatal. Historically concentrated in the American Southwest, the incidence of Valley fever has surged, with cases tripling in California between 2014 and 2022, according to the California Department of Public Health (CDPH).

Despite its rise, Valley fever remains underdiagnosed due to its symptom overlap with other respiratory infections, such as COVID-19. “Knowing when the Valley fever season starts and how intense it will be can help health care practitioners know when they should be on high alert for new cases,” noted Justin Remais, Ph.D., a professor at UC Berkeley School of Public Health and the study‘s corresponding author.

Seasonal and regional patterns of Valley fever

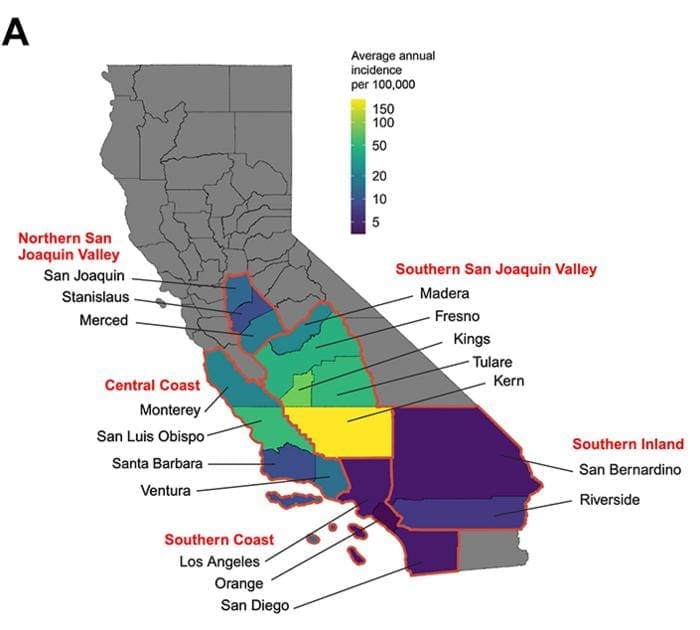

The researchers analyzed Valley fever cases reported in California from 2000 to 2021, correlating these with seasonal climate data. They discovered that while most cases peak from September to November, the intensity and timing of these peaks vary by county and year. The San Joaquin Valley and Central Coast regions, in particular, exhibit the most pronounced seasonal surges, with earlier peaks in the San Joaquin Valley.

The study also found that drought years saw a temporary dampening of these seasonal peaks.

“Most seasonal infectious diseases show a peak in cases every year, so we were surprised to see that there were certain years during which few or no counties had a seasonal peak in Valley fever cases,” said Alexandra Heaney, Ph.D., the study’s first author and an assistant professor at the UC San Diego Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and Human Longevity Science. This led the researchers to investigate the impact of drought on the disease’s seasonality.

Drought and its complex impact on Valley fever

The study hypothesizes that drought conditions may reduce Valley fever cases temporarily by decreasing the prevalence of competing organisms in the soil. However, when rains return, the drought-resistant Coccidioides spores are able to proliferate rapidly, leading to more severe outbreaks.

Another possible explanation involves the role of rodents, which can carry the fungus. Drought conditions often lead to rodent population declines, potentially concentrating the nutrients available for the fungus, thus enabling its survival and spread.

“This work is an important example of how infectious diseases are influenced by climate conditions,” said Heaney. The study’s findings underline the complex relationship between climate events like droughts and the spread of Valley fever, suggesting that the long-term effect of more frequent and severe droughts due to climate change could be an overall increase in Valley fever cases.

Preparing for future surges

The research emphasizes the importance of targeted public health messaging during the peak Valley fever season, especially in high-risk areas. Individuals can protect themselves by limiting outdoor activities during dry, dusty periods and using face coverings to block dust.

The team plans to extend their analysis to other Valley fever hotspots in the U.S., such as Arizona, where the disease is even more prevalent.

“Understanding where, when, and in what conditions Valley fever is most prevalent is critical for public health officials, physicians, and the public to take precautions during periods of increased risk,” Heaney concluded.

This research provides crucial insights for mitigating the impact of Valley fever as climate change continues to alter environmental conditions in the American Southwest.

Journal Reference:

Alexandra K. Heaneya ∙ Simon K. Camponurib ∙ Jennifer R. Headc,d ∙ Philip Collendere ∙ Amanda Weaverb ∙ Gail Sondermeyer Cookseyf∙ et al. ‘Coccidioidomycosis seasonality in California: a longitudinal surveillance study of the climate determinants and spatiotemporal variability of seasonal dynamics, 2000–2021’, The Lancet Regional Health – Americas (vol. 38, 100864; 2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.lana.2024.100864

Article Source:

Press Release/Material by University of California – San Diego

Featured image: Valley fever, an infection caused by an airborne fungus, gets its name from California’s Central Valley, pictured here. While the disease is named for the Central Valley, in recent years it has become more common across other parts of California and the southwestern United States. Credit: Fred Rockwood | Flickr | CC BY-SA